► Two very scary Italian supercars meet in Wales

► ‘A cacophony of sound that invades your whole body’

► A famous CAR magazine twin-test from August 1992

Exclusive! Nose to tail, Roger Bell tests the new-to-Britain Ferrari 512TR against the car it was designed to take on, the Lamborghini Diablo. Twelve-cylinder cars come no more exciting than these…

Marcello Gandini would appreciate the sincerity of the Welsh we met, who saw in an outrageous car (and they come no more outrageous than Gandini’s Diablo) not a symbol of wealth to be scorned, but a fantasy to relish. Never mind that the Lamborghini is a rich man’s toy, and a badly flawed one at that. Three generations of them, a granny included, saw in the Diablo what Gandini intended: a fabulous machine all the more appealing for espousing the absurd.

We did not seek an audience with the rural Welsh, but their enthusiasm and interest was hard to ignore. We were based in Brecon, for a head-to-head confrontation between two Italian icons. The dastardly Diablo, the devil’s own car, was one; Ferrari’s revamped, restrained Testarossa, half-heartedly renamed the 512TR, was the other.

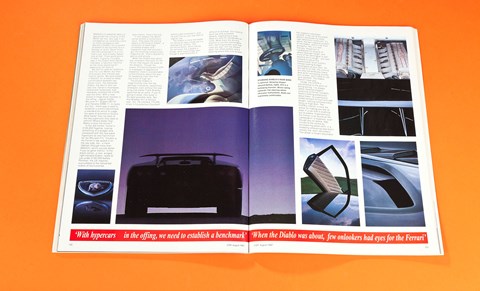

With a new breed of mega-buck monster in the offing – Jaguar XJ220, McLaren F1, Bugatti EB110 and Yamaha 0X99-11, to name but four – there was a need to establish a summit benchmark, a standard by which to judge the apex of automotive reverie. What better than the best of the two supercars they seek to rethink? Where better than Wales to pick the winner?

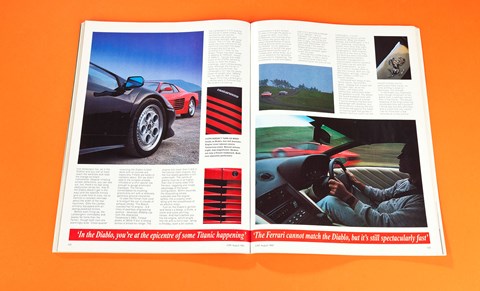

In the red corner, Ferrari’s £130,000 flagship, looking something of a budget ship compared with the new-wave hypercars (a cool half-million for the McLaren F1). Trouble is, the Ferrari’s top speed is on the low side, too – a mere 194mph (though more than 300km/h, which sounds better if you’ve gone metric). In the black corner, a rare, winged right-handed Diablo, listed at just under £150,000 before Portman, the UK importer, succumbed to the cancelled orders of disillusioned speculators, more’s the pity.

In one respect the Welsh extras settled a contentious issue. They gave the styling award to the bizarre Diablo – a collection of seemingly unrelated shapes and disparate lines that shouldn’t gel into anything cohesive but magically do. That is Gandini’s genius and artistry.

When the Diablo was about, few onlookers had eyes for the Ferrari that leaves me weak at the whatsits. Though the suave, Pininfarina-styled 512TR is a paragon of aggressive elegance, there’s a predictable conventionality about the way its sweeping lines flow from low snout to high tail.

The brutal Diablo is magnificently over the top, daringly innovative, awesomely endowed, even without the rear wing that owner Frank Bradley specified as an extra. If you’re going to pose, then pose in the best possible style. Not that Bradley isn’t a serious user, too. He clocked 115,000 miles in his previous Countach before yobs smashed it, and he puts the car you see here to regular use.

The Diablo is none the better for being as zany inside as it is spectacular without. The guillotine doors, which swing up vertically like a gadfly’s wings, work surprisingly well, though a dignified entry is difficult to achieve. You have to duck low and scramble aboard, negotiating a wide, deep sill and the handbrake en route. What mars the driving position is not the comfortable, semi-reclining bucket seat that cups you well, but the distant dash, the offset pedals and a steering wheel that cuts across the ungainly instrument nacelle. If the rim of the wheel doesn’t obliterate the dials, light reflections surely will.

It’s weird, the twin-capsule cockpit of the Diablo, and it’s far from wonderful. Nor is it user friendly. Headroom is inadequate for anyone of above average height, and most of the switchgear is well beyond arm’s length – you lean forward to adjust the heater/cooler push buttons (cheap-looking budget rectangles) at your peril. On the top of all that, the controls are also horrendously heavy. And as for conveying journey bric-a-brac, you’ll have to use your pockets. The Diablo doesn’t have any.

Inside, the 512TR is conventional to the point of being boring. I’ve always rather liked the elegant simplicity of Ferrari cockpits; there’s nothing pretentious about them, no superfluous embellishment to scuff and add weight, nothing controversially fancy or high-tech. The 512TR’s interior is none the worse for making you feel at ease in a car that is anything but mundane. Ergonomically, the Ferrari is as sound as the Lamborghini is hopeless, even though you sit askew, legs forced to the centre by encroaching wheel-arch, in a modestly embracing seat that’s merely low, semi-recumbent. The wheel is height-adjustable (not telescopic too, as in the Diablo) and you can at least reach the switches and read the orange-on-black instruments.

Despite irritating screen reflections, you can see out, too; there’s no rear wing obstruction (to be fair, that of the Diablo doesn’t get in the way) and the satellite mirrors give a wide field of view, not to mention a constant reminder about the width of the rear haunches. Ditto the Lambo, similarly equipped with all-seeing powered mirrors.

Before even firing up, the Lamborghini intimidates and teases far more than the Ferrari, though both cars are alarmingly wide. Close-quarter reversing the Diablo is best done with an outside aid, especially if there are kerbs or cambers about. Still we didn’t add to the scrapes already inflicted ‘on a chin spoiler low enough to gouge prominent Catseyes. The Ferrari consolidates its crushing practicality win with a relatively generous ground clearance.

To start the Ferrari from cold is to engulf the car in clouds of exhaust smoke. The Bosch-injected flat-12 engine – 4.9 litres of peerless engineering exotica – develops 420bhp (up from the displaced Testarossa’s 390). Torque peaks at 360lb ft but is strong across a broad rev range. The engine sits lower than it did in the tubular-steel chassis, but the five-speed gearbox is still underneath. The centre of gravity must be a lot higher than that of some older V12 Ferraris, negating one innate advantage of the boxer configuration. Within seconds, the disquieting smoke subsides and the engine settles into a creamy snarl, idling with the smoothness of an electric motor.

Turn on the Diablo’s ignition and there’s a bleep, a thunk, a clonk and some whirring noises. And that’s before you fire the engine, which erupts into life with a lion’s roar. Idling is throbby, even a bit coarse, the Lamborghini’s V12 lacking the Ferrari’s sweet timbre. Your sensibilities are quickly retuned to raw power and Herculean strength, With good reason. The 5.2-litre, 48-valve quad-cam that sufficed for the definitive Countach has been enlarged (by boring and stroking) to 5.7 litres for the Diablo. Power has been raised to 492bhp at 7000rpm, torque to 428lb ft – figures that make those of the 512TR, fettled by Ferrari to meet the Diablo challenge, seem comparatively tame. Although the Ferrari is lighter by around 2cwt, the Lamborghini still has the better power-to-weight ratio: 296bhp per ton against 268. It shows.

Never mind that Lamborghini is off the pace in Formula One. The Diablo’s blistering performance is plain wicked. To slam it through the gears is to goad the devil. Four-shot throbbiness that distinguishes the lumpy idle gives way to a deep-chested bellow of spine-chilling ferocity when you bury the throttle. It’s an awesome cacophony of sound that goes beyond assailing the ears; it invades your whole body, as if you’re seated at the epicentre of some titanic happening. The acceleration is just formidable (call it 4.0 seconds to 60mph, 8.5 to 100mph, 18.5 to 150mph). Top speed is over 200mph – as verified by our man in Italy, Giancarlo Perini (see CAR, September ’91) -which made it the world’s fastest production road car, until Jaguar usurped; again under our eyes.

Although the 512TR (0-60 in 4.5 seconds, 0-100 in about 11) cannot quite match the devastating all-out snort of the Lamborghini, it is still spectacularly fast by normal yardsticks. When the Diablo bellows, the 512TR wails. It is a rich, hysterical, intoxicating sound, more tenor than bass but no less exciting than the Lamborghini’s. Both engines, as docile at low revs as they are ferocious when extended, are magnificently flexible -electronic management of sophisticated injection systems eliminates low-rev tantrums and temperament – so you don’t have to scream them to feel their muscle. Both will lug effortlessly, willingly, cleanly; even 750rpm in fifth is a smooth doddle.

Compared with those of any family saloon, the 512TR’s gears – dogleg first is back left, top back right, as on the Diablo – are heavy and obstructive, particularly when the gearbox is cold. You attack the round-knobbed lever with the short-arm jabs of a boxer. If you’re trying to impress your passenger with dexterity, you do so without clanking the slim, chromed rod against the metal six-barred gate that guides it. Neither the fluid clutch nor the smooth throttle call for particularly hefty inputs, so slick shifting is down to technique, not strength.

In the Diablo you need both, even though movement of the gated lever is perhaps shorter than in the Ferrari. The abrupt response of the thigh-straining accelerator (the last Countach I drove was similarly afflicted), and a clutch that you cannot ride for more than a few seconds at a time without fatigue setting in, call for clay-digging effort. Throwing in the clutch to change gear is taxing enough; holding it down in traffic is for iron pumpers only.

After driving the Diablo, the Ferrari feels like a namby featherweight, its controls succumbing easily to inputs that wouldn’t budge those of the Lamborghini – for which there’s a clutch-assist option, by the way. If you’re buying one, have it. The Ferrari is the more economical car, too; over a five-day, 1000-mile period, it returned 17.9mpg, against a two-day return of 13.3mpg for the Diablo. Both cars are cat-cleaned so strictly unleaded.

Capitalising on their rearward weight bias, the secret of sensational traction, neither car has assisted steering. Both could do with it on manoeuvres, even around town where heavy demands are made on aching muscles. A strong, iron-fisted grip is needed when cornering hard, too. As lateral g increases -and it can attain prodigious levels in both these cars – self-centring forces rocket. The corollary of steering that gets heavier as concerning forces rise is wonderfully communicative feedback, heightened by wheel rims that writhe and buck.

Pootling along, the big Ferrari’s steering feels at best dull-edged if not exactly sluggish, even though it’s sharper than the displaced Testarossa’s. At speed, there’s no sign of the nervousness that makes the lesser 348 an edgy car. Nor do the big tyres induce any tramline deviation when lining up corners under heavy braking. Impeccable stability and balance is the 512’s hallmark.

If the Ferrari’s good, the Diablo’s better. The steering of the Lambo is a mite sharper, making it the niftier, crisper car when B-road hustling. Stable yes, nimble no. Sheer grip makes up for indifferent agility. On dry tarmac in the public domain, your nerve is always going to give way before the tyres – bobbin-reel 335/35 Pirelli P Zeros on the back of the Diablo – relinquish their grip. Circumspection, though, is the watchword in the wet.

Driven with normal restraint on spacious roads, both cars are tolerably civilised, bordering on the refined. Given smooth tarmac and still air, the Ferrari is as quiet at 80mph as your average family hatch; whoosh, swish and snarl merge as one boring background drone, cruising on the motorways at Sierra speeds. Only when flexing muscle is either car aurally stimulating. The Diablo’s decibel level is also throttle related; back off and the noise of the engine subsides, drowned out by tyre roar, that generated by ridged concrete being close to deafening. Both cars bobble and bronco-buck on stiff suspension that will loosen your fillings on pocked urban roads. In the Diablo – but not the quiet-riding Ferrari – you are aware of wishbone clonkiness and rubber thud, too. Tanking along out of town, jitters that mar the gnarled low-speed ride of both cars dissolve into a firm glide.

Colleague Brett Fraser observed that at high speed the Lambo feels the tauter, tighter car, that the Ferrari, its precision notwithstanding, is prone to lighten and float. He’s right. If you want a behemoth kart, the Diablo comes closer to meeting the bill than the 512TR. However, flick-wrist agility is an attribute of neither car. Sheer girth militates against the sort of wieldiness that would allow, say, a Lotus Elan to outflank both these leviathans on byways. Both have mighty ventilated disc brakes, of course, those of the Ferrari (clearly visible through slender-spoked wheels) a mite over-servoed when dawdling, the Lamborghini’s too heavy (what else?) when called into serious action at speed. On my scoresheet, whatever the Ferrari loses to the Lamborghini in outer-limit handling and grip – and it isn’t much, despite lesser 295/35 rubber – is offset by the ease with which it can be handled.

Brett’s line is that if you’re going on a limb, go the whole way. Go without compromise, go for the wacky Diablo. Forget that there’s not much in the way of a (front) boot, a ghastly dash layout, awful rear-threequarter visibility, marginal ground clearance and a climate-control system that mists the screen. I don’t see why wackiness should be quite so heavily penalised, or the finish so dreadfully patchy, but the Lamborghini goes its own, unique way, and who would have otherwise?

As practical transport, the half-sensible Ferrari makes for better wheels, if not quite such exhilarating ones. It’s less physical, more relaxing to drive with spirit than is the Diablo, the excesses of which can be cruelly intimidating. Dammit, I could live with the Ferrari. Would that I could.

Read more CAR archive features