► CAR magazine’s iconic April 1984 cover story continued

► This is Part Two – you can read Part One here

► ‘It is not a comparison – it’s a celebration’

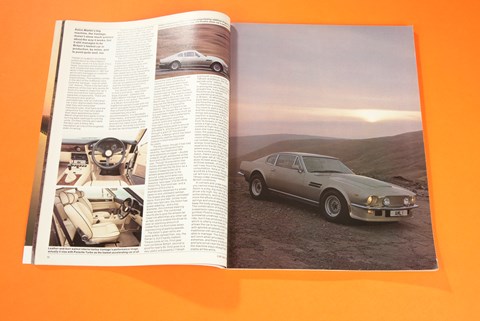

Aston Martin’s big machine, the Vantage, doesn’t show much science about the way it works, but it still manages to be Britain’s fastest car in production, by miles, and to point quite well, too

There is almost nothing subtle about an Aston Martin Vantage, once it’s fully built. It is a large, luxurious and brutish car with a body that was traditional when it first appeared in 1967 but which still manages to combine pleasing lines with its massiveness. The subtlety comes in the skill of the craftsmen who build the Vantage—and all other ‘old’ Astons. There’s the skill and patience of the man who works for most of a week to make the car’s alloy bonnet from half a dozen separate components. There are the people who graft so painstakingly over an individual car’s burr walnut dash that years later they still remember individual jobs. And there are the ubiquitous four men who spend their days assembling Aston Martin engines from parts in bins — turning bare castings to running units. On their infinite skill rests the twin-cam 5.3litre V8’s reputation as one of the toughest, even in racing.

The Vantage grew up out of the first Aston Martin DBS car, which was unveiled in 1967. That first car was six-cylinder powered; the V8 didn’t come along until several years later, though it had always been scheduled for this car. The higher-power Vantage version was a 1977 addition to the range; Astons had built more powerful versions of their DB cars and the builders aimed to follow history.

The 1977 Vantage had a peakier torque curve than the ’84 edition. It also had deficiencies of suspension specification and build quality that made it a difficult and untidy car to drive fast, especially over demanding country roads like the Welsh B-roads where part of this test took place. A thorough review of the car’s suspension took place and the Vantage turned into a tamer yet faster machine.

You would look for a long time to find a similarity—apart from bags of power— between the Aston Martin Vantage and the other cars in our group. The Aston is a 38cwt, front-engined traditional upright coupe-with-V8, which occupies more road space than a Ford Granada but has cramped two-plus-two accommodation. It is decidedly nose-heavy, and small hatchback cars a yard shorter run rings around it for cabin room. On the other hand, this body’s function, as well as carrying people, is to house the lusty 5.31itre twin cam V8 built in alloy and fed by a quartet of massive 48mm dual-throat Weber carburettors. This makes the machine Britain’s fastest road car by a very healthy margin indeed. The engine output is supposed to be a secret, Aston Martin say, but German law now requires the Newport Pagnell firm to disclose that it is good for 390bhp. This is no figure to be sneezed at, though the car has in the past been rated at as much as 475bhp. Astons have preferred to let the speculation push the outputs artificially higher rather than spell it out. A reliable estimated torque peak is around 375-4001b ft, and the push is fed through a giant ZF five-speed gearbox, a design which has been commonly used for big power outputs in front-engined cars for years.

The big Aston, though it has had suspension refinement fairly recently, has traditional AM arrangements on paper — double unequal length wishbones at the front and a De Dion system at the rear. Though its popularity has mostly died for production cars, Astons still rate the De Dion as a means of keeping the car’s wheels perpendicular to the ground, a key point when you consider that the Aston wears massive ‘rally-type’ 275/55 VR15 Pirelli P7s, front and rear, and a footprint of this size is dramatically lessened if a wheel takes on any untoward camber. The brakes are gigantic ventilated discs, front and rear. Unlike most other very fast cars, the Aston has power steering — and a big-diameter, thin-rimmed steering wheel as well. The combined results are to give the wheels far lower rim effort than any other car as fast, and to enable the driver to peel an alarming amount of rubber from his front tyres when manoeuvring at parking speeds.

The Aston’s gear ratios are more widely spread than, say, the Ferrari’s, but it hardly matters. Torque cures all ills. First gear runs out below 50mph, second is good for nearly 80, third goes to a very useful and powerful 114mph and fourth is showing a true 138mph at 6250rpm, the ‘short periods-only’ redline.

There’s no doubt that the Aston is among the very fastest cars in a straight line. It vies with the Porsche as the fastest accelerating production car sold in Britain; its effortless kick in the back feels even more instant than the Porsche’s when you floor the throttle from a constant 120mph. You have to wait a long time to find the conditions where such things are possible, but the reaction is worthwhile. The engine just gulps at the air and growls from its bowels (it never really emits a high note, just a baritone rumble at high revs, rather than a bass one lower down). The nose rises, the gigantic bonnet bulge takes away even more of your vision of the road ahead and the car rockets onward, with the energy most fairly fast cars reserve for the 50-70mph area where every machine is supposed to have some punch. But in the Aston, there’s still 20mph of fourth gear left at 120 and the car does its best work right up there. At those speeds, of course, you can’t say much for the fuel consumption. Nine or 10mpg would be a fine thing, though the car will turn in a reasonable 14mpg under more realistic British conditions.

In corners and under brakes, you cannot miss the fact that the Aston is a big, big motor car. The driver sits high, too; as high as some saloons, and he notices more the efforts of the tautly-set springs and shock absorbers to keep the body properly tied down. The combination of these uptight suspension rates and the huge, gumball Pirellis makes for a somewhat unrefined, rumbling ride, but it has produced a chassis which is utterly vice-free and allows the car to be hustled along with aplomb at speeds such traditional old cars shouldn’t be able to manage. The Aston’s body will lurch when provoked to extremes, and there’s body roll and tyre scrub near the limit, but the machine stays straight and stable all the while.

Besides that, it has the curious virtue for such a big brute of being light to drive. The assisted steering needs concentration, lest the driver (who is resisting cornering forces energetically because the seats don’t help much) should put too much heft into his work and deflect the car untidily. But the gearing is high and he soon finds he can bang the big car back into shape if it gets a little wayward. The transmission is light, too; its change mechanism is right above the gearbox and the throw is fairly long, even though the lever itself is quite short. The big problem, at least for those not used to it, is the lack of definition across the gate. It’s possible to get lost while trying to select a gear in the middle of the three longitudinal planes (second to third) and this can be a problem when you’re trying to snatch a lower gear for a 510W corner. The big car’s bulk on the more narrow variety of British roads mean that it needs to be steered accurately — and this is made more difficult when the driver is distractedly gear-groping.

The brakes, though light, need to be used with considerable care to slow the big machine, and black brake dust is soon strewn on the wheel rims after a couple of stops from about a ton.

In tight corners, the big Aston feels a classic heavy-nosed, front-engined machine. Its tendency is always to understeer, though this has been tamed by those huge tyres and all the roll stiffness that has been built in. In fact, a virtue of this car and of all the machinery we drove so hard for these stories is that they did minimal damage to their tyres’ sidewalls because the covers were sufficiently large for the job and because even in the softest-suspended car, probably this Vantage, the body roll was well controlled. Of course, the Vantage is one car you can easily boot into oversteer in slower bends, using the massive torque to overcome the traction of the limited-slip differential, but this is a comparatively slow way to travel and it peels alarming chunks of rubber from the P7s. The nicest, cleanest way to drive Vantage’s taut damping keeps two-ton body under control. In fact, the car’s light gearbox and power steering makes it quite nimble handling fast is to keep the car straight, provoking neither oversteer or understeer, guiding it with minimal use of the powerful steering assistance, and using the massive engine power to fill in the straights you encounter. That way, the Vantage isn’t disgraced in Countach country which makes it very fast indeed. At the same time, such is the bulk of the big Aston on narrow, winding roads that the likes of a Peugeot 205GTi might well be quicker …

The exhaust note of the Aston strikes a clever compromise between being loud enough to let everyone know that the car’s the hotter version (though the blanked-off radiator and enormous boots do that quite well, too) and suppressing the mechanical noise and those noises of suction from the bank of Webers, which are inconsistent with its role as a stockbroker special. What the car lacks, among performance cars, is an edge on its throttle response from low down; to get action you must really prod it right open wide. It’s a little difficult to know quite who is the target buyer for a Vantage. We suspect it’s likely to be a monied mogul whose first priority is to buy British. The thing is, the car has all the trappings, looks and aura of a fine old walnut-and-leather British gentleman’s express but the tautness of the suspension and the road rumble and harshness which this and the gigantic Pirellis kick up, do quite a lot to harm that luxurious main.

Whether it suits the car’s character or not, the luxurious equipment is all there in the Vantage. The trim in our test car (once again we borrowed the transport of AML chairman, Victor Gauntlett), had brilliant cream upholstery with dark brown piping, plus inches-thick carpet mats on the floor and burr walnut (a £400 option in standard Astons) across its facia. The Vantage instruments are the traditional kind, black-faced Smiths dials arrayed in a pattern which has more than a touch of early ’60s DB4 about it. It still works well enough (at least with a too-big steering wheel for a driver to peer through). Why should they change it?

Though we’ve criticised its actual comfort quotient, the Aston has the most believable rear seat accommodation of any fast car about. It beats the Porsche 911 and 928S, the Jaguar XJS and Ferrari 400i, and competes neck-and-neck with the Ferrari Mondial, a car which can’t hold a candle to the big Britisher for outright performance. This might be enough to make many buyers prefer the Aston to all others, especially since there’s a boot the size of a smallish three-box saloon (though one half-filled with a spare wheel) to carry the occupants’ luggage.

For a top-price car, some of the Aston detailing is downright offensive. The garish ex-Jaguar interior doorhandles, the Chrysler cast-off steering column wands (those in an Escort work in a far more satisfying way), the strikingly low-rent US-sourced air-conditioning controls — surely those could have been pinched from Jaguar? — and the awkward ex-Ford array of door, ignition and boot locks which require the owner to carry four keys to various parts of his car, these are very poor detail features for which AML can only expect more criticism as the lowest common denominator of cars improves.

It’s a creditable old car, the Aston Vantage, the kind which, when it’s gone, will be sorely missed. But while it’s on the market at £47,499, the price of two Mercedes 500SEs, it seems more vulnerable to criticism. The power is there, but no longer the mystery, and it is the mystery that sustains the sales appeal of so many fast cars. Still, if the forecasts of burgeoning sales, especially in the US, which were made along with the recent announcement of AML’s full acquisition by the US interests who already have distributorship of the cars on the New World, prove true, then the Old Thunderer could be in for a new lease of life. A decade of continued production seems quite on the cards.

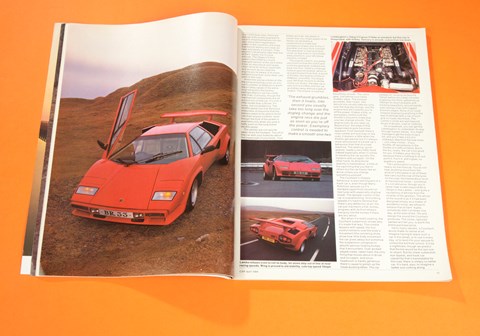

There has not been a more spectacular-looking car than Lamborghini’s Countach, nor is it likely. When we took it to the roads we affirmed that the car’s pretty damn competent there, too

About the lowest thing in the Lamborghini Countach is your own rear end in the driver’s seat. There you sit, not much more than four inches off the road, resting on a thinly padded bucket seat whose cushion is actually below the level of the side sills. The centre console, massively dividing the car’s wide, wide cabin, slopes upward towards the rear so that you’re cocooned between it and the door. The other side of the cabin seems yards away, you haven’t a clue where the nose extends, except you know it’s some way forwards, and the view to the rear is restricted to a slit of glass. That’s so close to your nose when you turn around that you can feel the heat from the engine bay it’s picked up.

It is this driving position which characterises your first driving period in a Countach, even if you’ve driven one before. All your usual relativities with known components are wrong. The car’s too wide, you can’t see its extremities — and all the while the computer in your head is telling you that the thing is worth upwards of £50,000 and you’ve really got to get to grips with it to report its behaviour sensibly.

Then what always happens, happens. You drive for a while, stop and do other things. When you step in again the Countach seems familiar. The driving position (Which you need to put effort into adjusting for yourself, via a ‘rocking’ mechanism and a fore/aft lever) feels familiar and your hands and feet are expecting to provide the heavy efforts that at first seemed so alien, even after the Ferrari. Somehow, your brain’s information store has assimilated info about the car’s extremities, and you discover that there’s a little hatch, no more than three inches square, beside and behind the passenger’s headrest, which provides you with rear three-quarter vision. In short, you have bent to suit the car; the Countach will never be compromised to suit your comfort.

Without a doubt, the Countach is the most spectacular and outlandish car you can buy from a new car dealer. Anything more spectacular you’ll have to take from a track and civilise, or build from scratch. Even then, it’s doubtful that you’ll reach that impossibly-crafted collection of planes and slopes and scoops and geometrical bulges that goes to make up the one car which can never be superseded. (Ever imagined a cosmetic tart-up on a Countach?) The closest the car ever came to a styling revision came with the 5.0-litre engine, when the aerodynamic gear was extended and the car’s side sills and wheelarches enlarged.

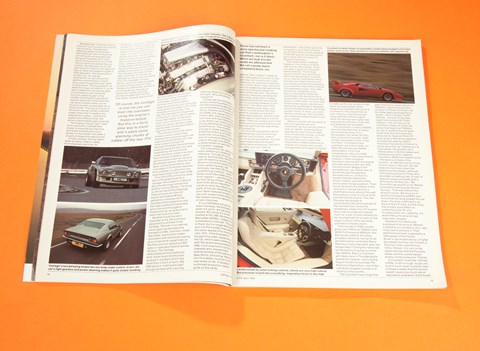

The Countach is heavy (34001b), short (inches less than a Jalpa) and extremely wide. It’s a remarkable 14in wider (at 79in) than a Vauxhall Cavalier, itself not the narrowest of cars. It has its 4754cc V12 engine (twin overhead cams each bank, six 45DCOE side-draught Weber carburettors, 9.2 to one compression ratio) mounted longitudinally in the space-frame chassis, in that unique-to-Countach manner with the engine mounted ahead of the rear axle line but turned 180deg to the conventional, say, Boxer way. It drives through the gearbox mounted end-on, so that it’s located literally beside the driver’s elbow, just behind the actual gearchange quadrant. Then the drive leaves the bottom of the ’box and is carried back by a shaft that tunnels straight through the engine’s sump to a final drive just behind the engine. This has the great advantage of concentrating the entire weight of the mechanicals inside the wheelbase, keeps the V12 engine fairly low-mounted and leaves room for a pair of side radiators to be mounted behind scoops on the upper surface of the rear body, just behind the two doors.

The Countach LP500 usually produces 375bhp at 7000rpm and 303lb ft of torque at 4500rpm, but the car we used for this story, privately owned by racing driver and demolition contractor Barry Robinson had a standard-spec but blueprinted V12 engine, reckoned by the factory to pump out more like 425bhp. Barry’s Countach will likely race in Thundersports events this season, carrying the flag of his family business TW Robinson Demolition, one of the half dozen biggest concerns of its kind in the country.

The Countach has a high first gear (maximum speed 55mph at 7000rpm), stacks second fairly close to it (75mph) and then has the other gears arranged fairly widely — third 112mph, fourth 143mph — but has its top gear lower than some at 25.7mph/ 1000rpm. The car tops out at 179.9mph if kept out of the red sector that begins at 7000rpm, though in practice the car goes faster than this at the top end because its massive Pirelli P7 tyres grow a little at top speed to increase the gearing. Barry Robinson has plenty of reason to know about the car’s behaviour at high speed. He recently set a whole series of British speed and endurance records, lapping Vauxhall’s Millbrook speed circuit — the best such track in the country— at 180mph true for hours on end, even in the rain. He has tales of a lurid spin down the banking at that speed, although nothing but praise for Pirelli who provided something like 15 sets of special-compound tyres (and a technician) for the runs. ‘We found the car would run at 180mph true without being quite flat out’, he says. ‘That was without the wing of course. We did a lot of wind tunnel testing at MIRA and found that the wing slowed the car down; the drag coefficient’s up around the 0.4 mark, but the wing has a really good effect on controlling yaw lift, and increasing the car’s stability. It’s worth fitting the wing for fast road work, anyway.’

Standard Countachs are supposed to do around 180mph. In practice you’d need a very, very long road to achieve it. Their performance level is generally a little ahead of the Ferrari Boxer’s (as evidenced by a higher top speed) but they can’t match a Porsche Turbo over the first 120 to 130mph. It’s only in the upper reaches that the Porsche eases and the Lambo keeps slowly climbing beyond 170mph. A Countach, even the ‘refined’ LP500, is still a rough, tough car, built in such small numbers (two or three a week) that the factory needn’t worry too much about legislation problems. Each buyer is an individual case; there are enough enthusiasts prepared to lie and cheat themselves into tax disc and a set of registration plates in the countries of Europe that barrier testing and clean air laws are barely a concern. They wouldn’t necessarily take that line at Sant’ Agata, but it’s true enough. The 70deg V12 that powers the LP500 is a much-changed version of the old 4.01itre. It has an alloy block and heads, chain drive for its four camshafts and as soon as you start the engine you’re aware of its more extreme tune than most other cars sold for the road.

It belches and grumbles at idle, the exhaust bellows even as you run it unladen at 2000rpm to warm the oil (they speak of the extra-loud exhaust in the factory; perhaps Barry’s car has come with that). Curiously, though the mechanical components are all around you in that car, it’s only a little louder than a Boxer. It’s noisy, but not deafening. The throttle pedal has that delicious sharpness of response that the Italians seem to be able to build into their engine controls, even though the bulk of the power is available only when you give a hefty push on the long-travel throttle pedal.

The pedals are not very far away down the footwell. You sit in this car with your buttocks about the lowest part of your body. Your knees are high, the wheel is closer than you might expect of an Italian car (probably a compromise to make that outrageous shape) and is tiny in diameter and very thick-rimmed. The gearlever is high and fairly close, so that even in its furthest-away positions, your left elbow remains crooked.

The engine’s warm, you press very firmly to free the clutch and snick the gearlever outward and back into first. There’s a manual lockout against reverse. which is straight forward from first. A touch of throttle; the engine climbs to 2500rpm, smoothly. You brace your left thigh muscle to let the clutch out slowly, the take-up is very firm but silken and the car grumbles away without a jerk or snatch. The engine is loud but beautifully smooth. The valve gear, just behind your head, chatters away. The exhaust grumbles, then howls. Into second you usually take too long over the dog-leg change, and the engine revs die instantly you’re off the power. It takes a blip, or exemplary control over the throttle’s closure to make that one-two change smooth. The engine roars as you open up. Beyond four, the edge of that blueprinted engine becomes apparent. From beneath there’s road rumble and tyre slap on the road, it lessens a little when the Pirellis get warmer but it’s always more reminiscent of a track car’s behaviour than that of a road machine. The steering, quick-geared, needs a very hefty hand indeed especially when it comes to handling the car quickly into hairpins and out again. On the other hand, its directional stability is tremendous; a little of the squirming that you feel in others but the car tracks like an arrow unless you change something yourself.

The Countach’s chassis behaviour is also reminiscent of a track car’s, even though Barry Robinson assures us it’s standard (apart from record run rear tyres with especially shallow tread). The damper control of the car is overwhelming. At trundling speeds it’s hard to believe that there’s any deflection at all; the car just maintains a flat, bumpy progress with its front wheels banging into the bumps if there are any about.

But when it’s really soaring, the Countach suspension shows why it’s made that way. The rumble lessens with speed, the iron control remains over the body’s movement (the cornering shots show how little body movement the car gives away) but somehow the suspension conspires to absorb serious-looking bumps that it encounters. Over wicked-edged crests, taken hard, the only thing that moves about is driver and occupant, and since headroom is hardly generous there’s cause to polish up the head-ducking reflex. The car sweeps on, singing up beyond 70mph before you need consider snapping into third, gathering up 100mph on short straights and tracking beautifully around bends, even bumpy ones with ragged bitumen edges. None of us could imagine displaying anything in the way of attitude with a car of such grip on roads like these. The Lambo’s limits are well beyond those of drivers, road or visibility.

On a racetrack, you can get the Lamborghini to understeer its way through hairpin bends. You might manage to get the body to jig a bit, and you’ll feel a bit of a sideways step from the rear tyres — just a few inches — if you throttle off senselessly in the middle of a difficult bend. But in the dry, really, the car’s too good for you. It flatters your driving because there’s nothing to do but point it. Point it, and it goes, no questions asked.

The Lamborghini’s noise is nearly all mechanical. You do not hear anything much from the wind (it’s the same in all of these fast cars) but the roar of the tyres on the road, the tremendous level of mechanical noise somehow it’s not obtrusive, though you’d never hear a radio beyond 60 or 70mph in the Lambo — and quite a cacophony of whines from the innards of the gearbox. The whole of the sound is as if it had been designed simply as a maker of wonderful noise; we refuse to believe that at Sant’ Agata, somebody didn’t sit down one day, at the start of the ’70s and design the sound the Countach produces. The noise, raptured owners will tell you, is worth the entire purchase price.

Yet to many owners, a Countach would make no sense at all. Imagine having to leave such a car in the street, or to use it every day, or to lend it to your spouse to collect the kid from school. It’d be a nightmare, though we predict that the kid would be the last one to object. But for sheer outlandish eye appeal, and track-car capability that’s translatable for the road, there is simply no better car. It’s hard, also, to imagine a better one coming along.

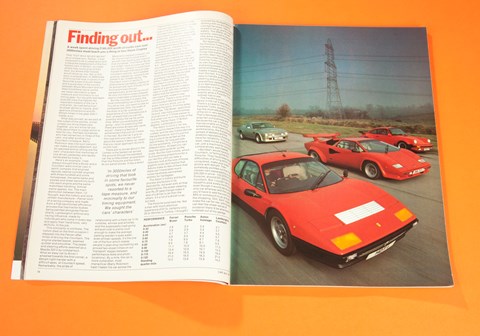

Finding out…

This test was never meant as a comparison. Rather, it was supposed to be a celebration and separate assessment of the four fastest cars in Britain, on roads there they could give of their best, but where their foibles, would show up, too. Nor is this story a comparison. In 3000miles of driving that took in some of our favourite areas of South Wales and a good deal of the country between Black Mountain and our West Smithfield nerve centre we never resorted to a tape measure and minimally to our timing gear. Our doughty test team took the view that beside the important matters of the car’s character, its road behaviour, its sheer ability to inspire, door aperture dimensions and 20- 10mph times in top gear didn’t natter a jot.

What was proved, as we said at the outset of the stories, is that unless you drive these cars together, you will know far too little about them to judge which is best for you. Perhaps somebody who has owned two or three of the cars, one after another (our Countach colleague, Barry Robinson was one such person) and make a good judgement, but so opposed and so strong are the cars’ characters that memories of one driven yesterday are rapidly obliterated by today’s.

Here’s an example. I had always thought that a Boxer and a Countach were similar cars in spirit; complex mid-engined layouts, twelve-cylinder engines with three hundred and some horsepower, the same barks and sizzles and sheer sensitivity built into each engine and the same matchless handling. The main, distinction between them, I’d thought, was the history and style if their manufacture Ferrari born of a racing company and made Tom a Fiat-sanctioned efficiency-process that has tractor bodies being painted alongside Ferrari shells; Lamborghini without any ‘racing influence, made by individuals who come in every day and apply their hand tools, very skilfully, to the job.

This similarity is not there. The notion died on the first occasion I stepped into the Ferrari after miles of driving the Countach. The engine started easier, seemed quieter and smoother. The pedal and steering efforts seemed as a Mazda 323’s by comparison. What an easy car to drive! I wheeled towards the first corner, a 35mph right-hander with a difficult apex, at Countach speed. Remarkably, the pride of Maranello stepped outward; not far, but enough to know that it wouldn’t be wanting any more of that nonsense. This Ferrari Boxer is a softer, more sinuous car than the Lambo. I reckon it could have flipped through that bend at near-Countach velocity, but it needed guiding, caressing, not just to be poked in as I’d been doing. The Countach’s turn-in ability is phenomenal (probably a factor of its almost total lack of body roll or front-end kneel) though paradoxically at the racing circuit its only inclination when pressed was to understeer a little too much.

But the Countach is easily the most intimidating car of the bunch. You sit so low, you seem to see so comparatively little, the width of the body is so far outside your experience (it’s a Granada plus a foot, at least) that you cannot possibly enjoy the car for some time. When you eventually get going and I’m predicting that there are some drivers who never would -there’s a feeling of achievement that just isn’t there in the rest. But the car’s grip on the road and your own caution about the space it takes up, mean that you never approach its limits on the road.

There are no bones about it, the Lambo is the fastest car across the ground (though the standard car has a little slower acceleration than the Porsche and the Aston, as our panel shows. It has a direct relationship with a track car in its rumbles, whines and whistles, and the supposedly road-going exhaust note is plenty loud enough to make the average parking warden’s eyes water, even at town speeds. It’s the one car of the four which makes people’s jaws drop (something we proved two-dozen times on our `transport’ stages between performance tests and photo locations). By a mile, the car is more outlandish, most impractical (Barry Robinson hasn’t taken his car across the Channel because he has doubts it would negotiate the ferry ramps; how’s that for a limitation). The Countach also lacks much in the way of body protection, specially at the rear, and the imagined cost of a new crank or a set of front-end panels is the kind of money businessmen take to Brazil.

The Ferrari, therefore, is an exquisite compromise. The essential car has a purity and a sophistication which has seen its appearance in sports car races (though it is decidedly a road car) but – apart from a sad, sad lack of any boot room whatsoever -the car is quite practical to drive. It’s flexible, it’s quiet yet sounds quite lovely from inside, has durable and easily handled controls, doesn’t need anything like the Countach’s control efforts, yet really, its performance in the hands of a good driver is damn near on a par with the Lambo’s. Add to that the fact that it really can cope with modern road conditions. There’s none of that old Countach feeling that with every mile you drive, you’re outside the spirit, if not the letter, of the law. The Boxer, apart from its boot, has many practicalities. And service is 17 times easier to find when you’re in the ends of the country. Ferrari have 17 British dealers; Lamborghini one.

The Aston is out of it, for me. You’ve got to respect the way it’s crafted, and the way it does deliver the performance, but it’s just too big a lump to be as fast as the rest of these, for long periods. On the autobahns, it might be a different story. At least you can hear the radio quite far up the scale. But the road rumble, which is of surprising proportions for a car like this until you take a leisurely look at the size of those gigantic tyres (and realise that Astons make so few of them that there can’t have been much noise-harshness earmarked entirely for Vantages).

The Aston’s history and build process are factors in its desirability, but even with all that performance, the power steering and iffy ZF gearchange make it less of a driver’s car than the others. It’s a lot of a driver’s car, but less …

The Porsche surprised me. Not a man with much previous experience of 911s, certainly only 20 or 30miles in Turbos, I thought I scorned the Stuttgarters for sticking with so ancient a concept because, I felt, they were scared to let go and try new waters. The 928S2, driven recently, seemed to prove that the new-wave machines just weren’t exciting enough.

But against these other cars, the Porsche Turbo is a very, very impressive machine. If performance and handling are the things that matter here (and not archaic dash layout and sunroof switches under the dash) the Porsche Turbo can cut it. It has on its own the smooth, silent, self-energising power of its KKK exhaust blower engine; that makes it seem more effortless than the rest. It is exceptionally easy to handle with lightish steering and a foolproof, wide-spaced four-speed gearbox that is no detriment to performance. It dawdles in town. It has body protection. And people know exactly what a Porsche Turbo is; nobody has to ask.

The handling quirk is even a factor in the car’s desirability. There’s a case for saying that the Porsche Turbo, expertly driven, has the most adjustable handling of the lot in very serious cornering. That’s because of the power-off, snap tail-out business and because the car’s naturally manoeuvrable on its short wheelbase. And there’s the terrific workmanship, the Europe-wide spread of dealers and the endemic reputation Porsches have for reliability. This one, at least, need not be a millionaire’s car, just a machine for somebody comparatively well-heeled.

I decided I would have the Countach, or failing that the Porsche. They have reserves and difficulties of driving which, when conquered, make your scalp prickle with delight. Then somebody pointed out that I had chosen cars separated by a cool £23,000 in price – £33,878 for the Porsche, around £57,000 for the Countach. But, I couldn’t bring myself to pick solely the Porsche, even though it would serve as an only car whereas with the Lambo you’d have to add the cost of an XR3 or some such to go and get the shopping. Still, Sant’ Agata make the car for me; sitting here I can feel the sheer sense of occasion there’d be whenever it rumbled out of my garage.

Performance: Acceleration (0-30/0-40/0-50/0-60, in sec)

Ferrari Boxer: 2.8/3.8/4.7/5.8

Porsche Turbo: 2.3/2.9/3.7/5.4

Aston Vantage: 2.4/3.2/4.4/5.5

Lamborghini Countach: 2.7/3.7/4.5/5.7

Performance: Acceleration (0-70/0-80/0-90/0-100, in sec)

Ferrari Boxer: 7.6/8.9/11.1/13.4

Porsche Turbo: 6.5/7.8/10.5/12.6

Aston Vantage: 6.7/8.1/10.0/12.1

Lamborghini Countach: 7.8/9.5/11.5/13.3

Performance: Acceleration (0-110/0-120/Standing quarter-mile, in sec)

Ferrari Boxer: 16.4/21.0/14.2

Porsche Turbo: 15.5/19.5/13.6

Aston Vantage: 14.5/18.3/13.5

Lamborghini Countach: 15.9/21.0/14.2

Read Finding Out… Part One here