As if Porsche hadn’t enough problems! Sales have slumped as the world, almost inexplicably, has fallen out of love with its cars. And now that the recession is ending, a host of Japanese upstarts have carefully targeted the Stuttgart car maker’s ageing products.

First there was Nissan, whose 300ZX pointed its twin-turbo shotgun barrels at the 928. Then Honda unveiled the NSX, an aluminium-bodied mid-engined supercar, for 911 money. Now, in what is potentially the most worrying development of the lot, Mazda has unveiled a gorgeous new RX-7, which threatens the 968, Porsche’s new bread and butter model.

Mazda, fast gaining a fine reputation for sports cars, has long tilted at Porsche with its RX-7. The last one had outrageously overt 944-like styling, a sure sign of the car’s intentions, if an equally sure sign of Mazda’s want of confidence. Yet the old RX-7, 22 grand in turbo coupe form, was more a poor man’s Porsche than a serious threat to the 944. It was as half-hearted in marketing terms as it was on the road: a great turbo rotary engine propelled a very indifferent car.

What’s worrying for Porsche is not just that Mazda now has the engineering competence to tackle it, but that it now has the confidence to do it. The MX-5, eulogised around the world, did as much for Mazda’s self-esteem as it did for its standing among car enthusiasts.

The latest RX-7, likely to cost about £30,000 when it hits British roads in mid summer, is the company’s most convincing sportster since the MX-5, and its best looking. The styling was done by Mazda’s Californian styling studio, under Tom Matano, also responsible for the MX-5. There is nothing derivative or Porsche-like about it. It’s an innovative design, a synthesis of handsome curves, unusual shapes (like the almost oval doors) and imaginative forms. There is both an organic naturalness and a high-tech boldness about it.

The new RX-7 is improved in just about every way. There’s a new aluminium wishbone suspension, revised twin-rotor engine – now with two water-cooled sequential turbos, which boost maximum power from 200 to 241bhp and maximum torque from 195 to 2171b ft – and a new interior. The latest RX-7 is smaller and lighter than its predecessor, and it’s been a long time since we’ve been able to say that about a new sports car.

In the end, Mazda managed to pare about 1501b, compared with the old RX-7, itself no lump. This, despite a standard airbag, ABS brakes, side intrusion bars and further (heavy) sundries. Examples of pound-pinching include a smaller glass area (20Ib saved), an aluminium bonnet, aluminium jack and jack handle (Audi did the same thing on the 100, before forsaking its Jane Fonda diet for a Ronald McDonald one), downsized engine and intercooler radiators, the aluminium wishbones front and rear, lighter alloy wheels, and even lighter high-tension ignition wires and dipstick (now a spindly piece of wire). Further to cut flab, the new RX-7 is 1.4in shorter and 1.4in lower.

Performance, not surprisingly, increases handsomely. The new RX-7 can jump to 60mph from rest in just over five seconds, covers the standing quarter-mile in 13.8 seconds, and won’t run out of energy until just shy of 160mph.

Innovative it may be, but Mazda’s engineers – if not its stylists – clearly studied the outgoing 944 hard, before finalising the new car. This Mazda is within an inch of the Porsche both in length and width. Only in height – the RX-7 is almost two inches lower – does the tape measure show a big difference between them.

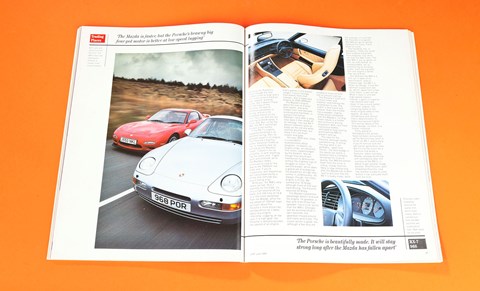

Because the RX-7 is similar to the 944, it is equally similar to the new 968 for, despite what your friendly Porsche salesman may tell you, the 968 is nothing more than a heavy revamp of the old car. While Mazda has come up with a brand-new sports car design (again), Porsche has fettled an old one (again).

Mind you, it hasn’t done a bad job. The rear wings, roof, doors and rear tailgate are all 944 carryovers, although the rear lights are different. Rather, the styling vivification comes from a new front end. The nose looks rather like the 928’S, with a touch of 959 thrown in. It’s curvier and more distinctive than the old 944’s. Given the depressed: state of Porsche in Britain, the new 968 is unlikely to be priced too greedily when sales start in late May. The talk is of about £35,000 for the coupe model, as tested, and nearer 40 grand for the convertible. That’s a steep price hike over the run-out, heavily reduced, 94452, but much cheaper than the 944 Turbo – which the 968 more closely approximates both in performance and handling – which was discontinued last autumn.

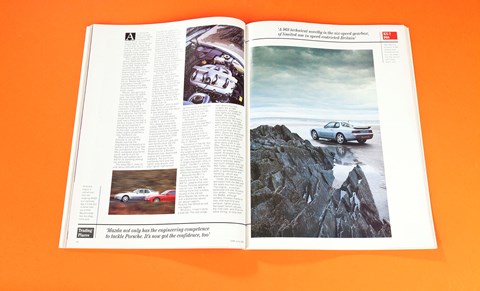

Inside, the dashboard is borrowed from the 944 and the seats are from the 911. The engine – a counter-balanced 3.0-litre 16-valve four potter – comes from the 944S2, although suitably titivated thanks to new inlet manifold and exhaust, lighter pistons, Variocam (which adjusts the inlet cam, and thus the valve timing, to help both low, mid and high rev performance) and a few other tweaks. The upshot is 240bhp at 6200rpm, up from the 944S2’s 211. Torque also blossoms from 203 to 221lb ft. (Notice the similarity of the Mazda’s and Porsche’s power and torque figures, gleaned from such different recipes.)

One Porsche powertrain novelty: the gearbox is now a six-speeder, sixth being a motorway-cruising overdrive ratio. It turns out to be of marginal use in speed-restricted Britain. As before, the gearbox and diff form a rear transaxle.

Other 944 carryovers include the old Turbo model’s suspension – front MacPherson struts and rear semi-trailing arms. Some of the components – the front lower wishbones, and the rear arms – are made from alloy, as before, to reduce unsprung weight. Never mind the prosaic on-paper story; anyone who’s driven a 944 Turbo will know that the spec sheet sells short one of the finest-handling suspension set-ups in the world. Our test 968 was further emboldened by optional sports suspension, which matches 17-inch diameter alloy wheels with tautened springs, dampers and roll bars.

The 968, then, is a traditional Porsche recipe: a heavily compromised basic design, but expertly and painstakingly developed. Nobody, in their right mind, would start with a clean sheet of paper and come up with a pricey sports car that features a 3.0-litre four-cylinder motor (think of the inherent vibrations) and such an everyday suspension set-up. Porsche, unable to afford an all-new car, is stuck with a development of the 924, launched in ’75.

Mazda has no such problems. The RX-7’s only major carryover item is the engine, and that’s a boon not a bind. The rotary has always been a superb mate, and it’s better than ever now that it has the twin sequential blowers. One of them gives boost at low and medium revs, the other turbo gives a helping shove when the revs build. The engine’s mated to a five-speed box. It is so quiet and unfussed at big revs, and revs so very easily, that a sixth speed would be a waste.

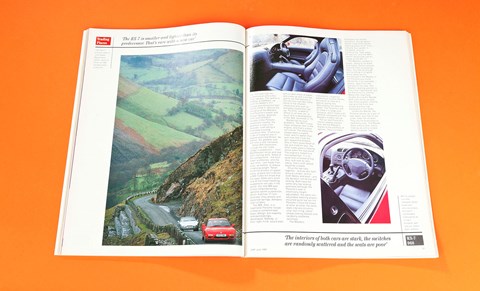

Drive the two cars together – and we did, both around London, and to north Wales and back – and the dynamic similarities are striking. Both have the same very row seating positions (although the Porsche’s seat is electrically height-adjustable); the same non-adjustable steering wheels, mounted quite low (on the Porsche it fouls the knees of taller drivers); the same stark interiors (crummy vinyl roof lining, rather cheap-looking dashes and randomly scattered switches).

The Mazda’s instruments, ringed by pretentious chrome bezels, are easier to read at a glance, being less obscured by the steering wheel. The Porsche’s are all sited in a large oval binnacle, which looks a bit 1970ish compared with the Mazda’s modern set-up.

Yet our test Porsche’s interior looked classier than did the Mazda’s, thanks to the plethora of options. They included handsome tan leather upholstery, the gorgeous leather-lined three-spoke steering wheel (a far more ordinary four-spoker is standard), plus air-conditioning. Take away the options, and the 968’s interior would look just as cheap as the RX-7’s.

The Mazda’s cockpit is cosier, owing to its wider and higher centre console, and the more enveloping dash. You feel as though you’re sitting in a fighter plane when you’re ensconced in the Mazda; in the Porsche you could almost be in an everyday saloon, apart from the lowness of the seat. The Mazda’s seating position is thus more inspirational, but the Porsche’s is roomier. Beefy men may have trouble driving the Mazda. Both cars serve up poor rear three-quarter visibility, owing to the thick rear pillars and the high backrests of the seats.

Unlike the Mazda, the Porsche serves up a pair of rear seats, but they’re too small, even for children. They are for briefcases or oddments only. The Mazda does without rear chairs, making do with a simple bench instead. Two lockable cubbies increase its usefulness. Both cars have similar front seats: quite thinly padded, heavily side bolstered and with high backrests. They’re equally uncomfortable: back ache was a common occurrence on long journeys. Both cars have smallish boots, blighted by shallowness.

The Porsche’s is longer and wider and thus bigger. Both luggage areas can be extended by dropping the rear squabs. The Porsche’s main problem, as we headed to north Wales on the M40 and M6, was road noise, so often the bane of German cars. On abrasive tarmac, or even worse, on concrete surfaces, the 968’s big Bridgestones hum any engine or wind noise or radio tunes to obscurity, and the driver to despair. Fortunately smoother stretches of tarmac reduce the decibel level. The sports suspension, as fitted to our test car, exacerbates the problem.

It also harshens the low-speed ride, firm on the normal 968, downright lumpy when you add the thicker springs and dampers and the lower profile 17-inch diameter rubber. Around London, the Porsche is one of the harshest-riding cars I’ve driven, and one of the least comfortable.

The Mazda is also firmly sprung, although its ride is less agitated around town. The road noise is also better suppressed, although the cabin of an RX-7 can still reverberate to the tune of bopping Bridgestones, particularly on concrete surfaces. Some motorway stretches, however, can unsettle the Mazda. On one section of the M40, peppered with unevenly laid slabs of concrete, the RX-7 developed a strange porpoising motion, which became downright uncomfortable. The damping of the front and rear ends didn’t feel quite right on that section of road, as though they were fighting each other. In most other ways, though, the chassis is impressive.

Once in Wales, up in the moors, the Mazda scampered over the bumpy, winding and undulating roads with great poise. The only Japanese sportster I’ve driven with comparable chassis finesse is the NSX, and that’s praise indeed. The steering, a little too light and vague at speed, is the only weak link. And you probably wouldn’t be aware of its faults unless you’d come straight out of the Porsche, whose tiller is wonderfully responsive at speed. The flip side, though, is its heaviness. Despite power assistance, the 968’s wheel requires real heft, particularly at low speed. It’s a heavy car to drive in almost every way -from the steering, to the clutch, to some of the switch controls, even closing the door. Muscle is needed to drive and operate the 968, but not the Mazda.

The 968 also feels heavier, less lithe, on the bumpy, testing moors. Its extra mass – the Porsche weighs about 2001b more -shows, and so does the less advanced suspension. Developing a flawed concept will get you only so far, no matter how expert you are at fettling. Another Porsche flaw is its tendency to tramline and follow the road’s camber under brakes. Again, the

optional sports suspension exacerbates the problem. Heavier and cruder it may be, but the 968 is still en obedient mate on the Welsh moors. The sheer competence of the chassis cannot fail to impress.

Try smoother, less taxing roads, and the 968 feels even better. There’s a great stretch of road on the way to Ffestiniog from Bala in north Wales, a big, wide, well-surfaced stretch, that the Porsche conquered with enormous aplomb. The 968 has a delicious handling balance, helped by the rear transaxle which shifts much of the mass to the rear, better to balance the front engine. No car would have been more fun on that road, no car faster nor more sure-footed. Nearing the limit of its roadholding, the driver gets warning of an impending drift, Even on the very limit, there’s a manoeuvrability and confidence-boosting wieldiness about the car. Back off mid-corner, nearing the limit, and the nose tucks obediently nearer the apex.

The RX-7 just doesn’t have this composure. It’s 95 percent there, its roadholding is every bit as good as the Porsche’s (even though the rear rubber is not as big) and it, too, is fun to punt hard on fast, smooth, winding roads. But it doesn’t have the delicacy of the Porsche. Its lack of communicativeness is telling, and so is its unsettled nature on the limit. You can feel the tail wanting to break away. It never did. But, unlike the 968, the RX-7 cannot be trusted at ten-tenths.

If the RX-7’s slightly wayward handling is its greatest failing, then its greatest asset is its engine. The Porsche’s big four-potter, balancer shafts or not, is nowhere near as refined as the Mazda’s motor: it doesn’t rev as smoothly, or with anything like the same zeal. It gets gruff and strained, while the Mazda’s rotary continues to sing all the way to the 7000rpm red mark and, if you’re injudicious, well beyond as well (accompanied by a chime that reminds you you’re being silly).

Mind you, the 968’s very nearly as fast. At 5.7 seconds for the 0-60, it’s only a half-second off the pace. A 0-100 time of 14.9 is a little more detached from the Mazda, while the top speed of 152mph says as much about the Porsche’s more block-like aerodynamics as it does about any engine inferiority. Lugging, at low revs in a high gear, the Porsche is actually quicker, the upshot of an engine

that’s gutsier in the bottom ranges. It pulls strongly from barely more than tickover, and is especially brawny at 2500-4000rpm.

The Mazda’s engine, about the size of a small beer barrel, and quite hidden from view beneath trunking and manifolds, is gutless from below 2000rpm. Only after a jerky step does it then shake off its lethargy. The new RX-7 doesn’t stammer quite as badly as the old one when tootling around town, but there’s still too much snatch and grab.

Yet over 2000 revs, there is a wonderful seamlessness about progress: no booms, no engine zings, no vibrations. The rotors, supercharged by the blowers, feel as though they would spin themselves to destruction without the slightest sign of struggle or strain. The second blower, which does a grand job of energising the powertrain at high revs, comes in unobtrusively. As always, though, the rotary engine is thirsty. We scored only 18.3mpg, although much of that was hard driving. The Porsche returned 22.8mpg.

The Mazda’s powertrain advantage doesn’t end with the engine. Its gearbox, a fast and short-throw five-speeder, has a nicer action than the 968’s. Changes can be accomplished in split seconds, the gearlever moved around with mere wrist flicks. The clutch action is good, too, although a few revs are needed to move off from rest to prevent stalling.

The Porsche’s stick shift is much firmer and notchier, and nothing like as pleasant to use. The clutch is less fluent and heavier. Even the throttle has a wooden, slightly sticky action compared with the Mazda’s; its long-travel nature is a further disincentive to driving enjoyment. Both cars have marvellous brakes, ventilated to help cooling, and boasting ABS to prevent lock-up.

The case for the Porsche, although hardly overwhelming, is strong. You buy what is still probably, – apart from Ferrari – the best badge in the sports-car world; a product from a company renowned for its build quality. Our 968 felt almost hewn from the solid: a classy, sturdy machine, likely to stay strong long after the Mazda has shaken itself to hits (not that the RX-7 is badly made; quite the contrary, it’s just that the Porsche is so good). The 968 will go on giving pleasure for many, many years to come.

The handling, too, is wonderful. There has never been a better balanced front-engined, rear-drive car than the 944 Turbo. The new 968 is just as good: so fast, so sure-footed, so manoeuvrable, yet so entertaining on winding roads. Even the big bore four-pot engine is better than you’d think.

But whereas the 968 is a fine car in spite of its specification, and its inherent age, the RX-7 is better by design. It has the optimum suspension set-up, which, apart from a few minor flaws, is well set-up. What it loses in ultimate high-speed chassis finesse, it gains in superior ride comfort and road noise. It has a much better, if thirstier, engine. The intriguing nature of the rotary engine adds to the appeal, as does its smoothness and almost manic determination to keep revving ever higher. The daring nature of the body design, so fresh, is a further incentive.

Thirty grand or thereabouts (for prices have not been announced yet for Britain) may seem a lot for an RX-7, particularly if you’re familiar with the two earlier generation cars. But it’s not too much for a machine that beats a Porsche, albeit narrowly. Mazda, already brimming with confidence after the success of the MX-5, is about to get another image booster. And Porsche, poor embattled Porsche, now has another hurdle to jump before it can extricate itself from the mire.

First published in CAR magazine, June 1992