► We revisit our January 1989 drive of the Cizeta V16T

► It’s the supercar that Lamborghini should have made

► 6.0-litre V16 engine produces 540bhp and 400lb ft

Built by a group of former Lamborghini engineers in Modena, powered by a V16 engine, and styled by Countach designer Marcello Gandini, it is precisely the sort of car Lamborghini’s next supercar should be – but won’t.

In a back-street of Modena, behind locked doors, men who created the first Lamborghini Countach are putting the finishing touches to its true, spiritual successor, a car with a brand new 6.0-litre V16 engine and a projected top speed of well above 200mph.

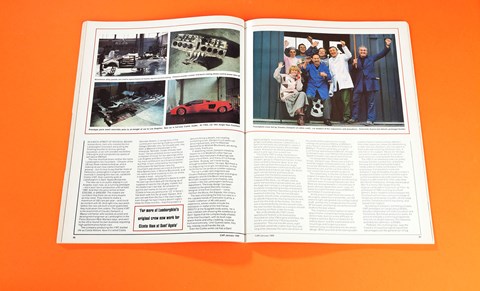

The new machine bears neither the name Lamborghini nor Countach — Chrysler of the US has those names locked up, and is making its own new-name Countach anyway — but it’s true to say that far more of Ferruccio Lamborghini’s original crew are involved in creating this new car, called the Cizeta V16T, than currently work at, Lamborghini in Sant’ Agata Bolognese.

The new car is on public display in Los Angeles, even now, as a running prototype — but it won’t be in production until at least 1990. And then the price will be at least £250,000, or $400,000. The makers are confident that there are as many buyers as they need.

They intend to make “a maximum of 100 cars per year—and could be content with 50. And right now, two years before the cars are built or even publicised, they hold seven firm orders. The Cizeta V16T is the brainchild of Claudio Zampolli, a 49year-old Italian who worked as a test and development engineer at Lamborghini in the Paolo Stanzani/Bob Wallace days, and went to the US to found his own business importing high-performance Italian cars.

The company producing the V16T started life as Cizeta Motors. Now it’s called Cizeta Moroder Motors, in recognition of the contribution now being made by composer Giorgio Moroder who, for the past year, has been a 50percent shareholder in the enterprise.

Moroder, holder of three ‘best music’ Oscars and best-known recently as composer of music for the openings of the Los Angeles and Seoul Olympics, is making his main contribution as a financial backer, but that, in turn, is backed by his long-time enthusiasm for fast Italian cars (his Countach was always serviced at Zampolli’s Italia Sports Cars, in Wilshire Boulevard), and his name will lend credibility to the car where it needs it most — among the rich.

Cynics might say Zampolli’s desire to make his own car coincided with the drying-up of supplies of cars for the US grey market, but he insists it isn’t like that. An ambition to put his own name on his own supercar (Cizeta is how you pronounce ‘CZ’ in Italian) has been with him for at least 10years. And you can see from the fire in the man’s eyes —even though he hasn’t had a decent night’s sleep for three months — that this project is about fulfilling a dream, not creating something to sell. Zampolli’s LA exotic car servicing business, and his Maserati dealership on Wilshire Boulevard, are doing very nicely, thank you.

In disarming mood, Zampolli insists he means no ill to Modena’s other fast-car factories. He’s had years of dealings with every one of them, and many of his friends are there. ‘Anyway, we’ll never be big enough to bother them,’ he says. But there is no disguising his single-mindedness, or that he thinks he can produce a better supercar.

The car’s under-skin engineers are Oliviero Pedrazzi (chief engineer and engine designer) and Achille Bevini and lanose Bronzatti (suspension and chassis), who worked in the old Lamborghini technical department. The body design has been created by the great Marcello Gandini, designer of the first Countach — not to mention the Miura, the Espada, the Urraco.

The task of building the first-run cars is in the capable hands of Giancarlo Guerra, a master craftsman of 40-odd years’ experience, whose credits include the realisation in metal of the first Ferrari 250GTO at the Scaglietti body works. He is also credited with showing the workforce at Sant’ Agata that the complex body-chassis of the first Countach, with its multi-tube space-frame and alloy cladding, could be built economically. Until Guerra came, they say, nobody could handle the job.

Even the Cizeta works cat has a Sant’ Agata pedigree. A somewhat lethargic ginger-and-tabby creature, called Ciccia, it spent its first years at Lamborghini, where it became attached to Guerra, the prototype maker. And when he left for pastures new, about a year ago, Ciccia went, too.

The Cizeta V16T is a big, meaty Italian supercar. Its cabin is very far forward in the modern, group C-influenced manner. In fact, it has no distinct bonnet ‘deck’ at all; the nose rises up from the road at an angle which the windscreen continues to the roof. The doors and windows are large; the doors open conventionally and have small cutaways into the roof to assist access.

There is a bubble-shaped rear window instead of the steep, cut-off type used by some transversely engined supercars, and the huge rear canopy is a magnificent alloy sculpture incorporating bumps and strakes and scoops, that then becomes a wing at its rearmost extremity. The car has US-spec bumpers at both ends, unobtrusive but able to absorb impacts by moving inward on rails built into the ends of the chassis. The front one is faired perfectly into the smooth nose; the rear bumper doubles as a wing to smooth air flowing out from under the body.

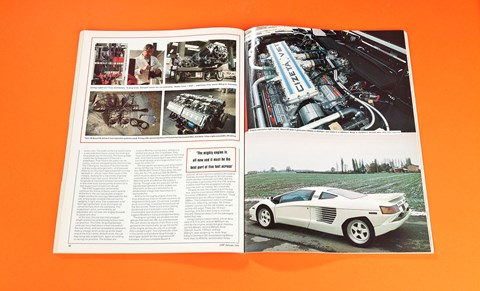

But undoubtedly the V16T’s most spectacular feature is its transversely mounted all-alloy V16 engine of 6.01itres, the world’s one-and-only V16 proposed for production. This one has 64 valves, eight overhead camshafts (rather than four very long ones, because the cams are driven at the centre of the engine block’s single casting) and produces 540bhp at 8000rpm, and a fraction less than 400lb ft of torque at 6000rpm. That lot is probably enough to push the top speed beyond 200mph, though, as Zampolli says, over 150mph the smallest speed increases cost a great deal of power.

‘I’ve always been fascinated with big things,’ Zampolli says. ‘Since I was a kid I’ve liked the largest, most powerful cars. I don’t knock the V8 Ferraris and Lamborghinis, they’re fine cars, but the car that carries my own initials has to be something special.’

This, essentially, is why the car has a V16 engine. It makes the car unique, Zampolli says, when 12-cylinder engines are becoming common even in mass-produced cars. And there are obvious benefits in smoothness of power delivery. Apart from which, when it’s really revving (it has been beyond 9000rpm by mistake) it sounds glorious.

All the power is taken from the centre of the engine, where two crankshafts, one left and one right, are geared into a single output shaft, and fed into a longitudinally mounted ZF transaxle, and then by conventional half-shafts to the rear wheels.

The chassis is a fairly traditional tubular space-frame, comprising mostly square-section tube, built on a very stiff base of elliptical sections. But it is notable for its orderly layout, and the way brackets and mountings and hinges have been harmoniously incorporated into the whole design. When you look at the stark powder-coated chassis it seems entirely different from older supercars, where the after thinking is often obvious. Zampolli, who has spent at least a decade restoring old Italian cars, is very hot on this subject. ‘Above all,’ he says, ‘we want to make a car which is not a let-down when you look beneath the surface.’

The V16T is an extremely wide car, partly because Gandini wanted it so, and partly because the mighty transverse engine needs width to nestle comfortably in the engine bay. It all dovetails nicely with Zampolli’s ‘big’ philosophy, though London’s prospective Cizeta owners had better watch out for suburban road width restrictors. The Cizeta is a little more than 3.0in wider than the Ferrari Testarossa, already very broad at 78in. It is nearly 10in longer than the original Lamborghini Countach, at 175in. Its wheelbase of 106in is as big as a Ford Sierra’s. And in height it comes between the Countach (which has a serious shortage of headroom and stands only 42in off the road) and the Testarossa (which has plenty, and stands 2.5in higher).

According to Zampolli, the first two Cizeta V16T prototypes will weigh about 3750lb, broadly comparable with both Countach and Testarossa. But before production starts, he plans to instigate a slimming programme that will cut weight radically. The objective, probably too optimistic, is 31001b. Pedrazzi, the chief engineer, says the Cizeta’s unusual but logical layout has advantages over the general run of big exotic cars. The width of the car (particularly a very wide front track) allows the seating to be pushed very far forward.

The trailing edge marks the halfway point of the car’s wheelbase. That means the cabin can be roomy, and not cramped by the mechanicals. The V16 engine, because of its short stroke and dry sump arrangement – and because there is no Countach-type propshaft running beneath it-sits far lower than usual in the chassis, making for a low centre of gravity and first-class rear vision. And the ‘thin’ longitudinal transaxle between the wheels in a very wide body leaves plenty of room for a rear suspension of optimum design.

The V16T suspension and brakes continue the theme of Swiss-watch quality. At the front, the car has double unequal-length wishbones (lovingly fabricated for the job, and powder-coated) that connect to uprights in light alloy. The suspension is by Koni spring/damper units which pick up conventionally from the wishbone. The suspension arms, connected by an adjustable anti-roll bar, are angled forward to assist anti-dive.

At the rear, the car also has unequal-length wishbones and broadly follows race car practice. This time, its spring/damper units are mounted about a foot inboard of the rear wheel, and are actuated by bellcrank from a linkage which picks up at the lower end of the hub carrier. At both ends, the car has rising rate suspension, again according to racing car practice. The brakes are massive Brembo racing discs, drilled and slotted and about 12in in diameter. They have twin-pot calipers, are identical front and rear, and mate to race-style hubs which have five locating pegs and a large central nut to keep the wheel on.

The five-spoke two-piece cast alloy wheels are by OZ Racing. The 9 x 17s at the front run 245/40 ZR17 Pirelli P Zero tyres; the rear rims are 13 x 17s, and use 335/35 ZR17s, which must be about the squattest road tyres in existence. In fact, the low profile of the rear tyres has quite an effect on the Cizeta’s styling. Though wide, the tyres are not the big diameter gumballs of the middle-era Countach, so the car cannot echo its predecessor’s huge rear haunches as a styling device.

And so to the mighty engine. From the blue and yellow lines on its cam covers to its magnesium belly-pan, it is all-new. Located on its mountings, it must be the best part of five feet across. There is one block casting (produced and machined in one of the innumerable specialist businesses that support Modena’s many prototype builders).

The engine cylinders are divided into two groups that look like V8s, but only because the cam drives, by duplex chain from a cog geared to the crankshafts, go up the centre of the engine as they do, say, on a vintage Alfa’s straight-eight. Two crankshafts meet in the centre and produce drive through a bevel gear system for the longitudinal ZF transaxle. And two complete Bosch K-Jetronic V8 fuel-injection systems are used to feed the monster through its 32 inlet valves (there are four valves per cylinder). But the firing order is genuinely that of a V16, and the makers insist that the powerplant should never be seen as ‘merely’ two linked V8s.

Despite its size, the engine is built for big revs, and the short stroke of 64.5mm, mated to a bore of 86.0mm, confirms the fact. Those dimensions give an official capacity of 5995cc. The compression ratio is a relaxed 9.3 to one, reflecting, perhaps, the Cizeta makers’ concern for the US market, as well as that of Europe. There are 10 main bearings, and the entire lump is inclined forward 10deg because it can be packaged better that way.

Using Cizeta’s chosen ratios, a final drive ratio of 4.11 to one, and an 8000rpm rev limit for the engine, projected gear maxima are first 60mph, second 90mph, third 125mph, fourth 170mph and top 204mph. And weighing no more than today’s Countach QV, but producing 85bhp more than its 455bhp, acceleration times must surely be in the spectacular bracket: 0-60mph in 4.0sec, 0-100mph in 12.0sec, 0-120mph in 18-20sec. It’s hard to imagine anyone complaining about a lack of power. Especially along Wilshire Boulevard.

In fact, the engine and transmission has already been driven there. Zampolli bought a Ferrari 308 in the US during 1987, cut it into three pieces and installed his engine and transaxle for test purposes. The car went very well, he says. It was smooth, powerful, docile, but noisy (there was no soundproofing) and wildly over-geared. But it was entirely reliable. Then it ran for a week on the dyno in Italy, the same one used for testing Alfa Romeo’s racing engines.

This was where it achieved 9000rpm-plus, though the rev-limit is 8000. The Cizeta engineers were highly encouraged by the engine’s general robustness – and saw an initial power output of 485bhp though their testing focused on proving general durability. As a result of that experience, the gas flowing of the ports and combustion chambers is now being modified.

Zampolli, though a seasoned resident of LA, is completely dedicated to Modena as a place to build a car like Cizeta. For one thing, he has the place in his blood. What is more, he is doubtful that any other city in the world could provide the small craft businesses which support the manufacture of fast cars. ‘Modena is the city of the fast car,’ he says with finality. ‘You could not build a Rolls-Royce in Japan.’

Yet, for all the Italian heritage, the Cizeta’s design has been much influenced by lessons Zampolli has learnt from his US customers. ‘I think Americans are the toughest customers of exotic cars in the world,’ he says. `Elsewhere, people are more understanding about breakdowns and problems because they know the car is special. Over there, they just want things to work.’ That’s why the V16T has power steering (a ZF rack and pinion system). It is why the car has first-class air-conditioning, tested with more than the usual degree of Italian thoroughness (When cars are tested here, they always go fast. There is always a good flow into the air intake. But in LA, it’s not unusual to average 15mph for an hour.’)

US demand is also why the car has big doors, a roomy cabin and plenty of seat travel. Americans, especially the successful ones, are big. That is why the instrumentation consists of only two big white-faced dials, speedo and tacho, and why there are sophisticated warning lights of graduating colour (culminating in flashing red signals) for other functions. CI don’t believe people look very much at little gauges,’ Zampolli says with disturbing directness.)

Thus the idiosyncratic nature of the Cizeta V16T comes more clearly into focus. Here is a car of thoroughly modern layout, produced by some of the world’s best technicians – for £2million spent so far – but it reflects the desires and prejudices of just one man: Zampolli. He has controlled the direction his designers have taken, every step of the way.

A complete chassis was then devised, and built in stainless steel box sections, before Zampolli vetoed its complication and the fact that the fabricated sections took up valuable space. Gandini produced an earlier body design than the present one – and even built it as a full-size model – before Zampolli vetoed it. ‘It didn’t make me excited,’ he says. ‘I thought it should. I agonised for ages, but finally called him up and said I didn’t like it. He was very good about it. We can’t modify it, he said, we’ll have to do a new one. So that’s what we did. Later he confided that he wasn’t so keen on the first shape, either.’

It’s this certainty that Zampolli has about his car, this clear vision about the way things should be, together with the ceaseless pursuit of quality, that is so impressive about the project. Enzo Ferrari, they say, had the same certainty from his earliest days as a car constructor. But Zampolli, a quiet man who reveals his ambition only to sympathisers, would be embarrassed by any comparison.

Yet this strong sense of direction -without the breath of a contribution from marketing men – has produced an unfashionable car, a car, apart from its V16 engine, which is devoid of `features’ that make easy headlines. There are no composite materials in the construction. Guerra probably wouldn’t recognise a carbon fibre component if it fell on him. There’s no height-adjustable suspension or dashboard rate ‘tuning’ facility for the driver. No 4wd system, despite the massive power. Turbocharging doesn’t get a look in – and this 204mph car doesn’t even have anti-lock brakes. And the car hasn’t yet seen a wind tunnel.

The omission of turbocharging seems sensible enough. No turbo engine could offer the throttle response you get from a highly tuned Italian multi-valve engine, and throttle response is where much of the pleasure of driving these cars comes from. On composites, Zampolli feels insufficient is yet known about their lasting qualities – over decades, he means – and he’d rather let others discover the disadvantages. Besides, buyers of ultra-low bodies love hand-wrought alloy fabrication.

He concedes a little on the non-adjustable suspension side. ‘The spring and damper rates can be adjusted by a dealer to customer’s specific requirements,’ he says. ‘We’re not trying to be dogmatic, and we’ll be very much geared to meeting individual needs, whatever they are. The car’s anti-roll bars are adjustable, so the handling can be adjusted. But each car will be set up by a test driver-whose job is to pick the best compromises. How many buyers can honestly know better than a factory tester?’

But Zampolli says he’s ‘very against’ four-wheel drive in cars like this. ‘In the Audi 90 Quattro it’s a different thing. That’s an all-roads, all-uses car. But in exotic cars, 4wd just makes for weight, complication, space problems and less-pure suspension geometry. I read an interview with Forghieri of Lamborghini where he was saying that a German driver coming south might encounter snow, then wet roads, then warm sun in the same journey. That justified four-wheel drive, he said.

‘Well, he may be right, but I don’t agree with him. My feelings are based on practical experience of the owners of these cars. I’m not inventing anything for them. I’m giving them what I think they want. A car like this-or the Countach, Testarossa, Boxer or Miura – is for fun and recreation. You don’t use it for serious journeys to the other side of the country. I know the owners. When it rains, they take the Merc or the Cadillac.’

Zampolli regrets not offering ABS, though. He believes in the idea implicitly. But the expenditure would simply be too great, he says. There is a suggestion, too, that when you’re launching a new car with a new name, big suppliers find it hard to take you seriously. ‘They think you’re making some kind of kit car,’ says Zampolli. As for the wind tunnel: Lamborghini never bothered.’ He says aerodynamic stability will be proved, or improved, on the road.

‘I went to see Bosch, because I think they make the best ABS. But they made it clear that it would cost millions to have a system for a car like this, with its power and performance, and tyres of different sizes. So for the time being there’s nothing we can do.’ But he does hold out the hope that when they see it’s a credible car, Bosch or another ABS maker may show greater interest.

So, this month, Zampolli reaches his first objective in a 10 year journey. The idea was germinated a decade ago, the first mechanical design began five years later, Gandini became involved three years ago -and finalised the body outline two years ago-and the business of detail design, setting up the workshops and making the prototypes, has been going on ever since.

Now, with the project on the record, there’s at least two years more work. And capital expenditure. After that, if there are profits, they’ll be modest. Zampolli and Moroder aren’t in it to make big money. Creating their own car is the essence of the thing.

\We don’t want to get carried away,’ Zampolli says. ‘I’d like to keep to a small workforce of about 30. We’ll do all the things here you need to keep tight control of quality, but we’ll sub-contract things such as casting and machining. The frames will probably be made elsewhere, too.

‘I’m not competing with the big names in Modena. They shouldn’t get upset with anything we do. But this car is my life. I want it to be the most exclusive as well as the best. And I’ll fight to keep it that way.’

Driving the Cizeta V16T

After three years’ work, they finished the Cizeta V16 just one day later than they’d predicted. That means trim, seats, hi-fi, wipers — everything. The only thing left out, by mistake, was the rear vision mirror that sticks inside the windscreen. Two exterior mirrors covered for it.

There was pleasure at the completion, but no excitement. Zampolli’s happiness, typically, was the private kind. ‘I’m very proud,’ was all he said. Guerra did take off his ubiquitous blue coat (with faded patch where a Lamborghini shield had been) for the occasion. And he did smile a lot. The rest of the people looked pleased, but also knew that tomorrow — once this fruit of their labours had disappeared into the belly of an aircraft bound for Los Angeles — the work would start all over again. There’s a second prototype to build before the Geneva Show.

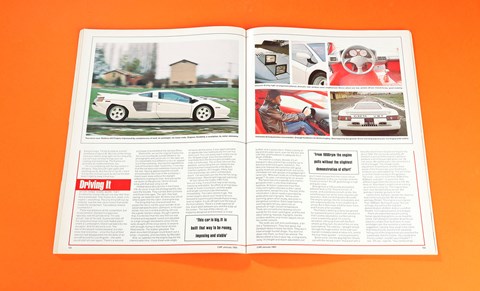

Meanwhile, we ran the original Cizeta into the rural countryside outside Modena, for photographs and just to see it in the open air. It’s remarkable how different a car can appear out of the workshop. Having first regretted its lack of Countach-style ‘haunches’, I now saw that the car does look extremely muscular at the rear. Having appreciated the smooth, almost bubble-like nose in the workshop, I liked it even more without the skylight reflections marring its lines. And seeing the car down on the ground, I think I’d have mine with that rear wing cut off.

I fretted about driving time in the Cizeta V16. As usual, it was the photographers who were the trouble. They wanted detail pictures and those took ages. The light, they kept saying, we need the light. So there was lots of time to peer into the cabin and engine bay.

The thing that has characterised this project for me is not the usual wonder at an advanced specification. (Zampolli, in his own words, has not invented anything.) It’s not the superb Gandini shape, though I admire that. It is the fact that this very first car was finished and equipped, tuned and adjusted, to a high enough standard to allow it to be sold, straight off the show stand, to anyone with enough money in their hand. All trim fitted exactly. The leather gleamed. The dash-mounted CD player could boom out a song — invariably, and inevitably, by Moroder.

And, as I peered into the engine bay for the interminable time it took three wide-angle lenses to do the same, it was again possible to appreciate how methodically this car has been built. You can easily reach every one of the 16 spark plugs. Even the two exhaust manifolds from the front eight cylinders can slide out with ease. The oil tank sits over the gearbox, surrounding the air intakes to the easily reached components of the Bosch injection systems. All linkages, filters, fuel lines and pumps are within comfortable reach. ‘I’ve serviced cars like this for too long,’ Zampolli says. ‘Reaching things was a priority.’

At last I drove the Cizeta V16T. First, this car is big. It is built that way to be roomy, imposing and stable. No effort at all has been made to make it compact, and the width and length communicate themselves immediately. The cabin seems huge. The screen begins above your head and runs forward to a point a yard ahead of your knees, and no higher. It cuts off right over the top of the front wheels. There’s a wide expanse of low, black dash between you and the base of the screen. The rest of the interior, all elegantly designed and trimmed, is in red leather and it smells like it. There is plenty of leg and shoulder room, even for the rich and over-fed, and headroom is adequate for a driver of 6ft 2in.

The interior is simple. As ever, it’s all Zampolli’s idea and he’ll be using the car to discover potential buyers’ reactions. The idea is to impress the customer with good quality materials and good finish, but not to intimidate him with gauges and gadgets he’ll never use. ‘Who ever reads an oil temperature gauge?’ he asks, not looking for an answer.

The facia has only a speedo and a tacho, grouped under a very deep leathered eyebrow. All Italian supercars have their instrument lights reflected on their raked windscreens, except this one. The rest of the information a driver needs is provided by graduated warning lights. Yellow when warming, green when ready, red when in dangerous condition. Extra large flashing warning lights tell you about low oil pressure or high coolant temperature. There are conventional steering column wands for the main switchgear, and the rest (door locking, hazards, fog lights, electric window switches and mirror-adjust) are on the centre console.

The seats are soft and comfortable, a bit like a Testarossa’s. They look great, but Zampolli doesn’t really like them. They don’t have enough bucket shape. You don’t sit down into them, so they’ll be altered. The Momo wheel is low in your lap, a long reach away. It’s height and reach adjustable, but you’ll never escape from the classic Italian driving position in this car. I wonder what the Yanks will think? The ZF gearchange is high and quite close.

Strange how a V16 sounds perceptibly different from a V12. They’re similar, of course, and seamlessly smooth at idle. But somehow you can sense more impulses per revolution. And a kind of double V8 woofle. The engine springs into life immediately and with surprising docility. It isn’t shattering or unruly. But it does have a 6.0-litre bass voice, and it snarls when prodded.

The Cizeta’s steering is fairly low-geared for a powered system (albeit with assistance that’s widely adjustable), but the turning circle is extremely good. It’s a funny sensation, sitting up there with the front wheels as they turn, the rest of the car way back behind. The visibility— straight ahead through the huge screen, to the side over Gandini’s steeply raked window-sills, and to the rear three-quarter — is truly panoramic.

Snick-snick, into the dog-leg first. Slowly out with the racing clutch, heavy but with a beautiful short travel. Engine turning at only about 1500. The car moves smoothly off. Zampolli is proud of the engine’s ability to produce a lot of torque right down low. He has cause. We gather pace. Into second it’s a bit of a struggle. The linkage needs adjustment. A brief burst, and the sheer power of the thing snaps your head back, whatever you were expecting. This will not be a car that needs rowing on the gearbox. The snarl — up to no more than 4500 of the 8500rpm available — is awesome. And different again from the shout of a V12. We drive on. Now there’s a tight corner coming up and this is a big car. The huge brakes, even cold, feel beautifully secure. But perhaps I’d better go back to first.

I select third. Zampolli, beside me, does his best not to look pained. We are doing perhaps 20mph. The engine is pulling less than 1000rpm. But it pulls away. Not just willingly, but without the slightest demonstration of effort. And on a whiff of throttle. It is hugely powerful and torquey.

Fears are expressed about hovering Italian spy photographers, so we head for home. I tell Zampolli I’d rather drive his car back to London than fly Alitalia. In most prototype cars, this would be a ludicrous suggestion. Usually, they weigh a ton more than they should, and the filler would be falling out of the body before you reached the autostrada. Not the Cizeta. ‘You could drive this to London, couldn’t you Claudio?’ I ask. ‘Oh yes,’ says he. ‘You could just go.’

Read more iconic car features from the CAR+ archive