► Russell Bulgin goes shopping in a rally car

► Ford Sierra Cosworth racer vs the high street

► A trip down memory lane in our CAR+ archive

I’m feeling a bit Malcolm today. Up pops an irresistible urge to jump in my full-works rally Q8 Team Ford Sierra Sapphire Cosworth 4×4 and trundle off, ego akimbo, to do the weekly shopping.

You know and I know that such a machine, with its titanium this and Kevlar that, is ideally suited for blasting Malcolm Wilson and co-driver Nicky Grist through Grizedale forest or around the Col du Turini in a speed-sharp haze of gor-blimey go-for-it. This car is the best Ford Sierra on earth. This car could be yours for £105,000. But can it pass the ultimate test?

Can it mosey down to Sainsbury’s in Croydon? Can it ease through the trolley-slalom outside Asda? Is it possible to cock a snook at authority and fly-park, with two Pirelli wet racers nudged high on the kerb, outside your local dry-cleaners?

You see, if you can’t indulge in all this mum and dad driving, then the works-spec Ford Sierra Sapphire Cosworth 4×4 us plain pointless. After all, the International Group A regulations, under which the Sierra dusts itself down in the World Rally Championship, are intended create ‘modified production cars’. If you can’t plunk a rally Sierra down outside Spud-U-Like for a hasty nibble on an oven-friendly King Edward, then the rally rules may as well be rewritten to allow Formula One cars to fly down the world’s forest tracks.

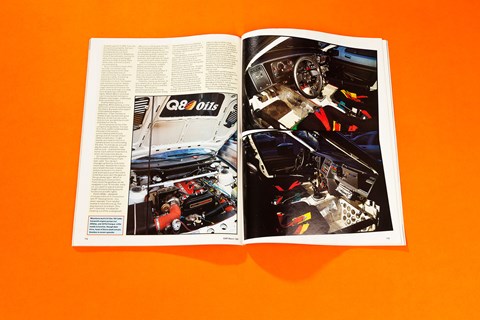

You need a quick-pre flight check before you drive off in a works Sierra. You also need the immortal words of Ford’s 60s rally ace Roger Clark – an arse like a parrot to get slotted down in the Recaro driver’s seat. A six-point harness cinches you over, under, sideways, down. Few things are familiar in the cockpit. The husk of a Sierra dashboard remains, as do the door-trims: these slivers of gentrification are about as relevant as a bidet on the Space Shuttle.

Pretty much everything else is buck-naked and painted white. There’s a roll-cage snaking through the cabin, tying the roof, the rear suspension mounts, the very structure of the car together. Look under the bonnet: the tubes pierce the bulkhead and wriggle onto the top mounts of the suspension in the names of occupant protection and chassis stiffness. Behind you is a fireproofed rear bulkhead clasping an accident warning triangle, with a sealed battery box, a silver fire extinguisher and miles of skinny Aeroquip piping seat replacing found the in a cropped humdrum velour Sierra.

Out on your driveway, you twist the red master-switch by your right shin, finger the switch marked ‘coil’, where the driver’s-side-air-vent should be, and prod the start button. After the churn comes a throb. To quell the gleam on the red alternator warning light you nudge 3000rpm on to the rev counter. A Rally Sierra needs, say the Ford Motorsport Mechanics, four or five minutes of idling enlivened by the odd blip-blip to loosen up for the day’s shopping.

This makes your house vibrate. This annoys the hell out of the neighbours. From the outside, there’s a distant whine from the engine and a deep choffle-choffle-choffle from the squashed-looking tailpipe. A nagging subwoofer grumble makes your floorboards quiver.

That’s a minor quibble, frankly. Inside, the Sierra makes Motorhead live at the Brixton Academy sound like a sweet whisper. At idle, the MS90 gearbox gives every aural indication of having been filled with gravel and assorted swarf.

With speed, the noise simply increases in its dissonant wilfulness. At certain revs and load you would swear that an uncoordinated midget with a pneumatic drill is trying to perforate his way into the car. A two-hour motorway journey in a works Sierra leaves you with a four-hour headache.

Earplugs filter the Stockhausen references out of the multi-channel soundtrack, quell the insistent nagging of the transmission, spate the mess of drones into an engine zing and a gearbox zang. But the car is never peaceful, always niggling with itself: if Q8 Team Ford is short of ackers, Nurofen would make a perfectly apt co-sponsor.

So far you’ve done pretty well. You haven’t flood the engine. (Touch the throttle before you press the go-button and it’s new plugs all round, please.) The temperature gauge is hovering about the 50-degree mark: 80 is warm enough, and at 90 the cooling fan cuts in with the insouciance of a Lockheed Tristar engaging thrust.

Now, all you’ve got to do is engage gear and move away. At least the clutch is light. But the gearbox is a seven-speed non-synchro unit. To engage a gear from rest – frankly, the actual ratio doesn’t matter too much as the Sierra will pull away in fourth – you push the clutch pedal to the floor and let it rise. As it comes up you fumble for a cog. Get it right and the lever snicks home. Get it slightly wrong and the gearbox makes a noise like a moose farting. Cock it up completely and the whole car shudders.

The official Ford Motorsport oral instruction manual for the gearbox comes in two parts. In Part One, you are told to belt the lever around the gate and worry not about any clangs, thunks or screeches so induced. In Part Two, you are told that the gearbox costs £25,000.

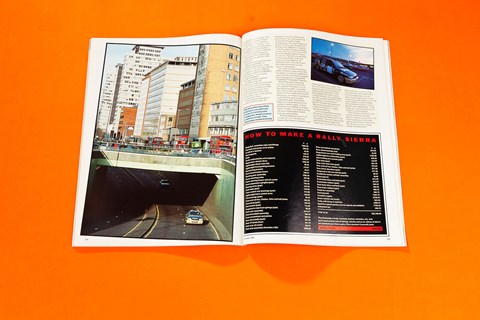

And it’s the only bit of the car the public can’t buy (yet). The official Ford Motorsport build manual for a Group A Sierra is an inch-thick, 11-language dossier packed with beautifully penned exploded diagrams: this is a Tamiya kit for grown-ups, two of whom will spend six full weeks in a workshop bolting together your shopping trolley.

Ford Motorsport’s no-secrets policy means the company, unlike all its tight-lipped World Rally Championship rivals, will actually sell you the bits you need to out-Malcolm the Q8 boys. A left-hand-drive, strengthened, roll-caged body shell, part number 9095012, is yours for £7500. Part 9094805 (engine, rally, for the use of) is £5750.

Don’t bother asking Kwik-Fit for an exhaust: the Pükka Group a system goes for £1400. If you are doing the job properly, then you won’t think twice about an anodised aluminium front jacking-point at £110. Wheelnuts come in two strengths: boring old steel, and luscious lightweight aluminium at £6.15 a pop. Rally fame costs, and here is where you start paying.

So you’re ready to head off for 100 rolls, microwave curry extravaganzas and the other high-octane essentials of suburban living. You need some revs to pull away. If reversing, please bear the following information in mind. The heated rear window is a goner. Neatly filling the spaces between the cage-tubes is a thick black net which looks as though it is made from King Kong’s old fishnet tights. Messrs Wilson and Grist use it to dump their helmets in between rally stages: it effectively blots out all rear vision.

And the steering lock is appalling. When parking, a nine-point turn comes as standard with this Sierra. But every other aspect of the steering verges on perfection. Power assistance makes it light, packed with good feel and, at less than two turns lock-to-lock, wonderfully smooth and direct on the fly. Dominating the centre of the cockpit is the gearlever. Formed from thick, battle-hardened steel, the base of the wand is surrounded by detents and springs and all manner of dullmetal complication. To get reverse, you have to haul on a cylindrical lock-out surrounding the stick. To change up, you just dip the clutch a traction — say half an inch — and slot the lever home. Each vertical movement is short, the horizontals less so.

Do it perfectly and the gearbox is the sweetest thing you have ever used. You zip-gun changes up the box, and clockclock down. Hesitate for a microsecond with the ever, however, and you’re stuck in no-man’s land and have to push the clutch to the floor and catch the gear on the up-stroke again. Which is humiliating at a box junction. Ford claims the gearbox can be swapped in just 10 minutes: early on, you seem to spend a similar length of time fumbling around for second at traffic lights.

Ford’s MS90 — designed in-house and built in conjunction with FF Developments — is a seven-speeder. From neutral, reverse is hard-left and up, first dog-leg back and down. (You don’t need first: it’s either for crawling out of the undergrowth after your co-driver gets a frog in his throat reading the pace-notes — or for letting the 4wd Sierra break traction away from the line for whizzbang starts.) Gears two to seven are straight up-and-downers, although seventh needs some care to be hooked cleanly.

I didn’t really know what gear I was in. I’m not alone: a digital display reminding the works drivers of their current cog-preference is being developed. If in doubt, you just whang the lever up or down and the Sierra responds beautifully. Malcolm, of course, doesn’t use the clutch.

I tried this. Going up the box, all you need to do is raise your right foot an eighth of an inch and slot the lever. The resulting gearchange will be as slick as full-fat cream and very fast. Doing likewise down the box defeated me: I could hit the right gear, but couldn’t engage it without a jolt or a shudder squirrelling through the whole car.

If the gearbox, when tamed, is wonderful, then the engine is even better. This Mountune-built Cosworth unit proffers torque to spare. Camminess, stumbling and general truculence are unavailable. This 2.0-litre, 16-valve turbo has, effectively, two modes and they are linked seamlessly. When the boost-gauge is showing —0.5 bar, the Sierra is docile, gentle and completely benign. You could actually drive this car for the rest of your life and never get the boost-needle above 0 bar.

You’d be missing something, though. Because when the boost comes in at around 3000rpm, the effect is like no other I have experienced in a car. This Sierra just cuts the nonsense and goes. Suddenly you are changing gear every couple of seconds and your depth perception has been completely out-fumbled. Details harden on the horizon. Not only does the boost needle flick around the dial in a demented two-step, but the rev-counter pointer does likewise. This bulky Cosworth motor revs like a hyperactive little go-kart.

I expected Ford Motorsport to do the sensible thing and give me a puny children’s chip in the engine management system — the brainbox, plus a spare unit already plumbed-in, sits ahead of the co-driver. Instead, I got Malcolm’s mighty microprocessor.

There’s a spindly little knob down by the master switch. The boost knob. It moves in clicks. One click is 0.1 bar. I turned it down to 1.3 bar in the rain —oh! how intoxicatingly pro-rally driver that statement makes me feel — and clicked it up again in the dry, close to the 1.8 bar maximum. The Sierra went from startlingly rapid to much too fast for me to comprehend.

Ford claims the engine pumps out 295bhp at 6250rpm: a gentleman’s agreement — stop smirking — in international rallying limits power outputs to 300bhp. Max torque is 407lb ft at 4000rpm and the ignition cut-out gets panicky at 7600rpm.

The way the Sierra goes is utterly intoxicating. No performance road car I have ever driven comes close to the sheer blood-and-guts hold-your-water wallop of the Q8-rocket. Ford claims a 0-60mph time of less than four seconds on dry tarmac. Or on a loose surface.

That’s the eerie thing about the way the Sierra goes. No wheelspin. A touch of front-end squirm is all. You just have to be on the ball enough to keep changing up. The overall gearing of the car is so ridiculously short — 16.7mph per 1000rpm in seventh — that the gearchanges just keep on coming. You want to know the rev-drop between gears? Sorry, no can do. Trying to concentrate on the road ahead, making a clean shift and keeping my heartbeat within bounds meant that reading the rev-counter was an impossibility.

Don’t ask me about handling, either. As far as I was concerned, this Sierra, on tarmac suspension and soft Pirelli wet racers, gripped like bubblegum on a bed-sheet. Understeer? Oversteer? Neither.

When they weren’t playing hunt-the-camber, those wildly corrugated Pirellis didn’t much like standing water or wet steel man-hole covers, giving the car a twitch the four-wheel drive tamed before you, a merely mortal driver, could react to each surface unpleasantness. The brakes, slabs of cross-drilled discs with carbon-metallic pads, worked brilliantly, but needed to be kept warm. In traffic, you kept pushing the solid middle pedal earlier than you anticipated.

And the Safeway’s stroll? Of course, this car handled the hassle. But there’s nowhere to put the shopping, unfortunately. The boot is full of a Formula One-style bag-tank and chunky OZ spare wheel. Dawdling this car is like taking Desert Orchid to a pony club gymkhana: of course Dessie can do his stuff in the St Trinians’ jumpathon, but what does it prove? Perhaps I did belittle the Q8-car by going down to the frozen food section in it. But I learned something.

It’s a cold November evening, the sky is turning the colour of burnt toast and there’s rain in the hills ahead. The forest track is wet and this RAC Rally stage is 18 miles long. You have to drive this Sierra flat-out on a slimy, high- crowned track, hemmed by tall, thick-trunked pines, in a car which is blindingly quick on the road and equally awesome on the loose. I spent a couple of days using the Sierra at about seven percent of its capabilities: in the forest, you have to extract its all. There is no turning back.

This is the point at which you have to make the ultimate decision. Are you a real man? (In which case you will whimper gently and call the whole thing off). Or are you truly, utterly, awesomely Malcolm?