► What we made of the Audi Quattro

► Our original review from August 1980

► Ronald ‘Steady’ Barker referees

When in March the arrival of the electrifying Audi Quattro generated a shockwave of excitement—consternation in some quarters — to ruffle the somewhat lethargic composure of the Geneva Salon, it sparked eulogies from the motoring press (including your very own Mel ‘O’Drama’ Nichols, who was one of the few privileged to drive one more than round the block: see CAR April). Yet I wondered: could the Audi really be that good? Was it so many streets ahead of the old Jensen FF?

One remembered the high hopes and expectations aroused 11 years earlier by Audi’s NSU associates with the elegant and beautifully mannered R080, powered by that magically smooth and unobtrusive Wankel engine; then the years of unfulfilled promise and the final surrender, when engineering and finances had been overstrained in vain attempts to stretch the Wankel’s longevity and contract its appetite.

New concepts never come to fruition without traumas, and when we point out manifest shortcomings the PR people will say: ‘Ah yes, we’re working on that’, meaning the problem has proved insoluble so far. Or ‘You have to remember this is only a pre-production prototype’ which can cover a multitude of sins, some of which may be erased. So, what was the Quattro really like? I wondered as I arrived in Germany to find out. It wasn’t the ideal weather for finding out, with the warm sun of midsummer on dry tarmac. Audi’s home town is Ingolstadt, previously the DKW stronghold, on the banks of the Blue Danube some 45miles north of Munich. Between the two is a rolling green landscape patched to infinity with pole-framed hop-fields, the largest area in all Europe devoted to the beer-swilling fraternity; It looks like being a bumper year for the hop vines; will it be a vintage year for Audi? At the moment they have people working overtime, weekends included, while Ford and Opel are on short time and laying off labour, and if the Quattro succeeds in international rallying, it’s bound to boost the Audi image and sales pattern.

So there’s no question of the Quattro being a desperate PR stunt or last-ditch stand, although company men will tell you openly that it sprang from an imagined need somehow to draw attention to the marque, perhaps as a prop against their own or public complacency. You have to anticipate such a need by several years, and the first-off all-wheel-drive Audi was running a full three years before the 1980 Salon, while the first 400 customers will still have to wait until the autumn for delivery. This project, then, began as a ‘let’s try it’ exercise, a technical adventure to try to pull something exciting but practical and saleable out of the bag without hanging a financial millstone around the company neck.

The Audi team had two considerable assets going for them: first, they had some experience of four-wheel-drive cross-country vehicles, especially the VW Iltis, and there were thus proven parts already on the shelf that might be adapted to the new project. Second, Audi had an advantage over previous high-performance all-wheel-drive experiments by being able to start the opposite way round — with a nose-heavy front-drive car to which they would add rear-wheel drive. One thing’s for sure: if one could plot graphs of rising torque and power versus those two front-drive aggros, acute ‘understeria’ and weight transference away from the undriven wheels when accelerating, they would show a stage beyond which the combination loses time on the stopwatch as well as challenging the driver’s skill and concentration. Alternative reprieves from this dilemma are the Audi’s all-wheel drive, or a complete turnabout like Renault’s metamorphosis of the standard four-seater front-driven R5 into the R5 Turbo, a mid-engined two-seater with rear drive.

With, say, 200bhp (the production Quattro’s output) to dispose of, dividing it between front and rear wheels halves the load as transmitted through the tyres, with enormous benefit to both traction and the slip angles that dominate cornering characteristics and control. Mechanical loads in the final drive mechanisms are likewise reduced so that off-the-shelf components never intended for 200bhp and high torque are not overstressed. Hitherto all-wheel-drives have generally involved considerable penalties in bulk, weight and cost, the dissipation of power through mechanical fosses and consequent heavier fuel consumption, extra transmission whines and clumsier controls. In the neat Audi layout every one of these factors has been knocked, if not for six, at least for a four. They even claim a benefit in fuel consumption from reduced tyre drag, offsetting the transmission losses.

For those unfamiliar with the Audi arrangement, here’s a broad outline in simple terms: in normal front-drive form the Audi engine and clutch are cantilevered forward of the wheel centres and the five-speed two-Shaft transmission is behind them, the pinion for the final drive set being on the front end of the gearbox output shaft, For the Quattro this shaft is replaced by a tubular one extended rearwards to include a coconut-sized hollow sphere carrying differential bevels. From inside this emerge, forwards, the front-drive pinion shaft running concentrically within the output shaft and, rearwards, stage one of the prop shaft to th9 back.

Centre and rear differentials have positive locks for use when conditions demand, and for leaving strictly alone on dry tarmac. Independent triggers to engage these are found beneath the central handbrake lever, and there are green tell-tales set in symbolic diagrams on the dash to remind the driver when either or both are engaged. Apart from these, which can.be applied even when the Quattro is moving fast, he has no supplementary controls or instrument dials to divert his attention, and his task is in fact simplified by the remarkable handling properties everyone’s raving about.

In the competition department at Ingolstadt I was shown one of several development cars involved in preparation for the international rallying programme, which could start with the RAC or the Monte, depending on whom you happen to ask. Before that, hot-shot Quattro’s may be baptised in a few local events; and the bhp figure now bandied about is 350. Magic Finn Hannu Mikkola has been engaged as much for his articulate analysis and interpretation of a car’s behaviour during the development process as for his established flair and success in competition. One assumes he wouldn’t have signed on without confidence in the potential of Dr. Audi’s Pushmepullyou against the spectacular techniques evolved by the rallying sodality for dealing with single-ended tractions Perhaps at this very moment Mikkola is out there somewhere in a secret forest, wearing out tyres by the quartet while mastering new tricks. It seems inevitable, though, that if the Quattro can match or better the opposition’, it will be less exciting to watch.

Great expectations for four-Wheel drive in GP racing a few years ago -came to nought because it wore out the drivers without winning them races. Circuit racing seems to demand independent control of each end, a balance between steering-wheel and accelerator, and today’s freak GP tyres can cope adequately with traction needs. Incidentally, the first-ever use of four- wheel drive in competition that I’m aware of was way back in 1902-3, the car being a Dutch Spijker which some believe also to have pioneered the six-cylinder engine. The actual car can still be seen at the Dutch motor museum.

As luck would have it, the best laid plans for getting fully acquainted with the Quattro were forestalled by super weather, so that it couldn’t display all its special tricks and by a supplementary deterrent — a tactical inability to shake off an undesirable Audi staff presence in the car. The only machine available seemed to be this gorgeous mother-of-pearl job, evidently too precious to hand over to a couple of Poms. Still, you have the Mellifluous pearls (April issue) to tell you how it behaves when committed on snow and ice to the unadulterated verve of an expatriate Tasmaniac!

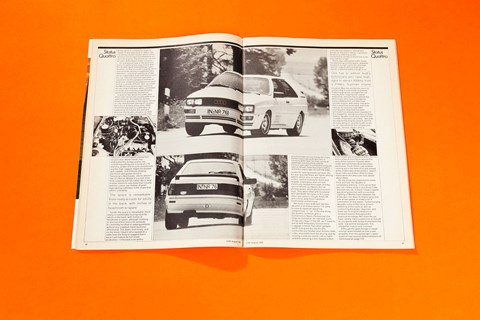

A word or two about the looks; and what sales brochures usually refer to as appointments. It’s certainly neither elegant nor graceful in the classic mould of, say, that pioneer among GT coupes, the Lancia Aurelia of the early 1950s. That form required no elaboration to emphasise or subdue any part of it, whereas the Quattro shape is so deep in relation to length that it couldn’t be

left plain. So the English styling man responsible, Martin Smith, has elaborated the dumpy profile into something putting one in mind of a TV starship, power and muscle compressed and the high, ragged-edged tail packed with rockets; and of those chirping electronic war games found in Tomorrow’s World pubs. (So he doesn’t like it?) Not so. Maybe it’s a near-miss from vulgarity but I do rather like it. How it looks seems to vary more than usually with the colour, our mother-of-pearl highlighting subtleties in the shape that others underplay.

Inside, the space is remarkable; there really is comfortable touring room for adults in the back, with inches of headroom to spare, although climbing in and out of that end is for acrobats. It’s decently finished in sober good taste, without any slapdash hand-built one-offmanship. The doors shut nicely, and on the move I heard not a squeak or a rattle from the body to suggest that it wasn’t yet mature for full-scale production. I criticised a car of this calibre for lacking electric window lifts, but was assured these will figure among options which also include cruise control, central locking for doors and tailgate, tinted glass and sun roof, electrically heated front seats and the special wheels as fitted to the car photographed, which are exclusive to Audi. They were fitted with Goodyear NCT 205/60VR 15in tyres in this case. Other tyre options include Pirelli P6 and similar wear from Firestone Continental and Uniroyal.

Because a very wide tyre like this absorbs a lot of boot space, I’m sorry to have to report an appalling compromise; in ‘ !00’ of the real thing, the Quattro customer gets a Convenience Spare (Temporary Use Only) by Goodyear. As I believe such things are illegal in the UK, we’ll have to put up with temporary Convenience Luggage instead. Two other gadgets worth noting are the electrically controlled and heated door mirrors, both sides adjustable from the driving seat by rocking a selector switch (left or right) and then pressing a ball-topped button in the desired direction; and what’s termed an electronic aerial, claimed to be twice as effective as the conventional variety so that it has to be only half the length.

These days adding the suffix Turbo, fast becoming commonplace, prepares people to accept claims for very high specific outputs without batting an eyelid, understandable enough in an era when Man has visited the moon to confirm that it’s not made of cheese. Turbocharging has salvaged the car industry from slipping into overall mediocrity, and one has to admire the technicians who have managed to extract 200bhp from a 2144cc five-cylinder engine, with every indication that it should be as reliable and long-lived as its normally aspirated counterparts. How that has been achieved has already been reported in this magazine, except possibly for three details: Quattro could also stand for the number of radiators provided — two side by-side for the engine coolant, one for its lubricating oil, and the fourth an air-to-air intercooler for the compressed charge. Second, there’s also a thermostatically engaged electric fan to duct a blast of cooling air around the area of the injection nozzles when under-bonnet temperature becomes excessive. Third, there’s yet another cooling aid in the form of Oil jets aimed at the undersides of the pistons, (which have nicks out of their skirts to clear them) when the pressure rises above about 35psi.

On the move the impressions come thick and fast: the Quattro is completely ordinary, in the sense that you can simply jump in and drive it like any ordinary car. It doesn’t have a space-age driving position with occasional sighting of Mother Earth between the kneecaps; nor does its engine gulp and jerk at low speed, or make a lot of commotion at any speed. Turbocharging absorbs some of the noise at each extremity of the cycle as well as cushioning the power impulses, and there are no engine vibrations or resonant booms throughout the practical rev range. Not does the car have ‘sporty’ hard suspension or disturb its occupants with bump-thump from the wide, low-profile Goodyears. It is altogether mature and civilised.

Although the gearchange is sweet enough when treated as one’s own property, from the passenger’s seat I experienced several demonstrations of the snatched change which had me worrying about what components might suddenly penetrate into the living quarters via the transmission tunnel. Not wanting to be rushed is inevitable when the ratio steps are so high — from 14.0 (overall) in first to an 8.27 second, and another fair jump into third at 5.29. The 3.76 to one fourth speed can be held to 210km/h, exactly 130mph, and in fifth the level road peak was about 137, with 140-plus on tap if gravity helped — all indicated speeds, mark you.

It’s no affectation to suggest that this Audi is well able to sustain 130mph, at which considerable velocity one can still chat without having to shout, or listen to — Susie Quatro perhaps! — on the radio. I cannot recall ever before feeling quite so secure at that speed, the Audi’s exact directional stability on the straight matched by an undeviating line through the curves, and backed by confidence that it will not lose its balance if you suddenly have to lift off.

With such a fusion of dynamic qualities, such performance linked with such traction and control, sybaritic ride comfort and low general noise level, the Quattro has to be today’s most significant motoring property.

It has set me wondering: which were its counterparts in previous decades? Now, there’s a cat to set among the pigeons, so I wouldn’t presume to offer these suggestions too seriously except as groundwork for a definitive list. It seems appropriate to start by looking back over half a century, to 1927 in fact, and the Bugatti Type 43 Grand Sport. Compared with the Quattro it had several things in common —a supercharged engine of not much over 2.01itres (2.3 in fact), a very high performance for its day, ditto handling properties, and cast aluminium wheels.

It provided its occupants (four at a pinch) with far more noise, mechanical vibes and direct fresh air than the Audi, and rather less in the way of riding comfort. With a top speed of 110-112mph it was about the fastest transport then available from the showroom, and among the very few catalogued cars that could be driven to a race meeting, carry off a trophy or two and be taken next day on a continental holiday.

In the late 1930s it might be another supercharged Bugatti, the 3.31itre Type 57C, a very different kettle of fish. Also a straight-eight, the T57 had plain bearings in place of rollers for its crankshaft which, combined with a more logical firing order, gave it a sweetness and flexibility which are still mighty impressive. The lower-built, sleeker 57SC was good for about 125mph when 100 was still a magic goal. A jump, then, to 1951 and the original

2.01itre Lancia Aurelia GT, one of the immortal classics (if the rust doesn’t win), virtually sporting derivative of a technically advanced family saloon. The compact, balanced proportions and unadulterated simplicity of its body form made this one of Pinin Farina’s chefs d’oeuvre. The original all-independent suspension was later replaced at the back by a de Dion axle, and the engine size was increased, but the body style remained almost unchanged through to 1956.

In 1952 there was another Grand Tourer on a rather larger and grander scale that still has a very special place among Bentley afficionados, the fastback lightweight coupe by H J Mulliner. It had the straight-six engine with overhead inlet and side exhaust valves, and an old-fashioned live axle on leaf springs at the back, but despite those archaic legacies it could reach about 120mph and cover the ground fast and in quiet comfort with four passengers.

A near-miss for commercial reasons was the Gordon GT of 1960, which grew into the Gordon-Keeble of the mid-60s. With its American Chevrolet V8 engine in a British designed and made chassis and a full four-seater body designed by Bertone, it was an extremely fast and impressive machine that could match the Audi’s 140mph. I can’t think that anyone would dispute including the Jaguar E-type, although the original open two-seater of 1961 might not qualify on grounds of limited room. The Chrysler-engined Jensen FF, although with four-wheel drive and Dunlop Maxaret anti-skid braking, was another near-miss in my estimation —too complex and expensive, and spoiled by the limitations of its live rear axle.

There has to be a Ferrari somewhere in the list, surely. My own favourite is the original V6 Dino of around 1965, but a two-seater cannot qualify. But no; the big four-seater Ferraris aren’t all that outstanding in the context of such a list. The Lamborghini Espada is of more significance.

Even considered against such a background, the Quattro shines (pearlescent paint or no). From where, and in what form, will come something, this decade, to top it?

Now the question has to be whether this vehicle will start a ball rolling, leading to a landslide into all-wheel drive for general use; is it really necessary where speeds are limited to 55-70mph, where all the roads are metalled and snow rarely or never falls? Long ago, when four-wheel brakes were beginning to replace two-wheel bakes, a motoring pundit was credited with this observation: ‘Granted that they help you to stop quicker, but when everyone has them, will anyone be any better off?’ Inevitably there had to come a time when no one could do without them; but the advantages of all-wheeldrive where road and weather conditions are consistently good and speeds are restricted would never be very marked.

However, one can bet that all forward thinking manufacturers will be trying to get their hands on a Quattro and starting experiments on the same lines. If the car proves successful (not necessarily invincible) in rallying and if, as we have reported, Audi are planning a proper family saloon with AWD, it seems likely that the safety pressure groups would try to compel others to follow suit. How far down the scale such a revolution might spread will depend upon the manufacturers’ costing, and perhaps on whether Audi’s claims for reduced tyre wear and fuel consumption with their system really can be substantiated. If AWD were to catch on in Japan as a status attribute, or even become a legislative requirement, then we’ll all be having it and no one will be any better off…