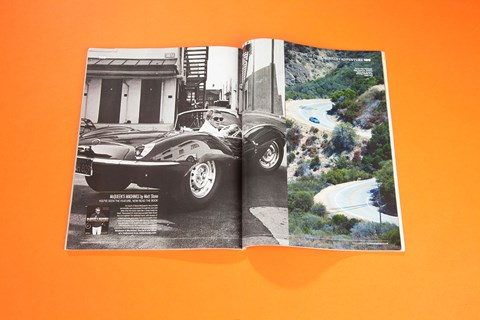

► Discovering the secret to Steve McQueen’s appeal

► Tracing McQueen’s ghost across Mulholland Highway

► ‘Full disclosure: I’m a Steve McQueen fan’

In a modern Jaguar – successor to his beloved XK-SS – along LA’s Mulholland Highway, via diners, aircraft hangars, old friends and the house where he lived his last days, we trace the ghost of America’s coolest icon

In August, a slate-grey 1970 Porsche 911S showing 112,000 miles and in fine, unrestored condition drove onto the stage at RM Auctions’ annual Pebble Beach sale. What happened next was pretty extraordinary. If the Porsche’s four registered owners had all been unknowns, it would have been worth $100,000. But it was first invoiced to Solar Productions, Steve McQueen’s film company, and was delivered to the set of his movie Le Mans, in which he drives it for the first four minutes. He shipped it back to California after filming, and sold it soon afterwards. That history and those four minutes made it worth $1,375,000 to somebody.

Full disclosure: I’m a Steve McQueen fan. In the old outbuilding where I write there are three pictures of him on the walls. That’s three out of maybe 50 pictures in here. I’m no stalker. I’ve seen most of his films, and happily admit some of them are terrible. But I’ve always wondered why I – and maybe you too – like him so much; why it’s okay for a straight man to have three pictures of Steve McQueen on his walls, but not Brad Pitt.

McQueen was a premier-league Hollywood star. His $12m fee for Towering Inferno in 1974 set a new record. But the power of his image seems to have grown beyond what his short but stellar career would suggest. ‘Iconic’ is a much-misused term but it’s used correctly here; McQueen’s image has become simple cultural shorthand for cool. He is the 11th highest-earning dead celebrity, and the brands he chose himself – Persol sunglasses, Heuer watches, Triumph and Porsche – lucked into the perfect free personal endorsement.

So how did this happen? What makes someone pay 14 times over the odds for a dead actor’s car? Maybe it’s because he didn’t want it to happen. Seeking adulation is the quickest way to kill it, and with McQueen it was always the reverse. He was intensely competitive as an actor, but the roles and the money always seemed to be the means to another end; to be left alone to do the stuff you and I would do if we had time and money. He collected, drove, raced, rode and flew cars, bikes and planes with discernment, passion and skill. The friends he made and kept were a stuntman, his karate coach and his flying instructor, not other actors. ‘Man, after I’ve gotten my sugar out of this business, I’m going to take off – and run like a thief,’ he told Life magazine as early as 1963.

So I’ve got a road trip planned. The Mulholland Highway does what Steve wanted to; leaves Hollywood for the arid isolation of LA’s canyon hinterland, where the roads are good and the people few. It ends near Malibu, where he moved to live by the sea, and from there it’s just an hour further to Santa Paula, the small town that he settled in before he died. Mulholland was McQueen’s favourite road, the venue for his late-night motorised badness; one story says the local cops had a prize of a big steak dinner for whoever could catch him.

Yes, it’s a little personal pilgrimage; I wanted to drive the same roads he did, stop at the same places and talk to some people who knew him. I didn’t set out imagining I’d discover the secret of his appeal, but I hoped I’d find a few of his traces.

And I wanted to reclaim McQueen as a Jaguar driver. Although he is most associated with Porsche, having won his class at Sebring in a 908 and driven a 917 in Le Mans, his favourite road car was probably the ‘Green Rat’, his 1957 Jaguar XK-SS. It was exactly his kind of car. As its Le Mans-winning D-type racer became uncompetitive, Jaguar was stuck with 25 it couldn’t shift, so it decided to turn them into barely legal road cars. Just 16 were converted before the factory fire of 1957 destroyed the remainder. McQueen first saw his parked on Sunset Boulevard in 1958; he bought it, repainted it in British racing green, had famed hot-rod artist Von Dutch make him a glovebox to hold his Persols and drove it like a bastard for the next nine years. He was endlessly photographed in it and terrorised Mulholland in it. He missed it, so in 1979, after two years of negotiations with collector William Harrah, he bought it back.

I wonder if he’d have liked our Jaguar as much. The XKR-S is only one letter and a misplaced hyphen away from McQueen’s car, but it approaches roadgoing hardcore from the opposite direction, sharpening up a big GT rather than softening off a racer. He’d have liked the name of the colour – French racing blue – if not the colour itself; too bright for his tastes. But it looks sensational in the fierce California glare, way bolder than it did when we first drove it in weak British sun. And the aerodynamic addenda look better here too; the wing and front air tunnels somehow more acceptable in a more flamboyant car culture.

We start at the Warner Brothers studios. It’s not like it used to be. The security guards love our Jag-waar, and reveal that George Clooney now sighs up in a Tesla Roadster. From here it’s a short drive to McQueen’s house on Solar Drive in the Hollywood Hills. We won’t get to explore the extra 40bhp our car offers over the standard 510bhp XKR on the way; all my attention is on avoiding the vast craters in California’s concrete roads, which seem to have gone completely third-world since Arnie nearly bankrupted the state. It can’t possibly have been any worse when McQueen was driving here; Jaguar might have stiffened the R-S’s springs by 28% and fitted wider rubber but I’m glad it hasn’t ruined the GT ride. Glad of the impressive sat-nav too, to disentangle the spaghetti of streets that access every buildable inch of these vertiginous and very desirable hills.

McQueen bought his house here when he was 30 and must have felt like a god. The air is cleaner and cooler up here than in the city laid out far below; you can’t see much of the house from the road, but it was beautiful. Quiet too; just the chirping crickets and cicadas. And 50 years ago, the blare of a barely-silenced straight-six breaking the Dunlops’ grip as another drive home in the XK-SS turned into a hillclimb.

Mulholland starts near here and heads west. Its best stretches are beyond LA, in the Santa Monica mountains around the town of Cornell. The machinery might have changed but McQueen would recognise the spirit. On a Saturday morning almost nobody uses this road to actually get anywhere. Stand on a corner and every few seconds brings another sports-bike rider with his knee fully down, or a big trail bike cranked over so hard there are sparks coming from the footpegs, or a caged-out 911 GT3 trying to keep up. It sounds like a track day, until the whump-whump of a police chopper sends everyone down to the Rock Store diner to calm down and have a coffee.

McQueen ate here, but also at the Old Place a little further down Mulholland. The owner, Tom Runyon, was exactly McQueen’s kind of bloke, a no-bullshit trapper and hunter who ran the tiny wood-panelled restaurant until he was 89, offering just steak, clams and baked potatoes. McQueen liked Tom so much he gave him a part in The Getaway. His son now runs it with the same no-bullshit attitude. And unlike almost every other commercial enterprise with a McQueen association it makes no hoo-ha about it. The barman has to point out the only reminder, some yellowed photos pinned to the back wall. ‘He used to come up here all the time with Ali McGraw,’ he says. ‘Nobody bothered him. That’s why he liked it.’ It may also have been the food and the atmosphere; we liked it so much we came back for dinner, when a local was banging out Folsom Prison Blues on the guitar, everyone else was joining in and it felt wrong not to be a little drunk. I wonder how McQueen got home to Malibu. I doubt it was sober.

I am, of course, when I get back into the Jag to drive the best section of Mulholland, The Snake, that heads west out of Cornell. The old saw about America not having any decent driving roads is untrue; this stretch is almost Alpine, with its long straight climbs to hairpins, or dizzying series of cambered switchbacks. Finally I can get deep into that throttle and add the supercharged 5.0-litre V8’s thunderous bass soundtrack to the screaming treble of the sports bikes. The big GT’s grip at both ends is mighty, its body control firm and flat and the brakes don’t go off despite the heat and provocation. It has a mighty span of ability, the XKR-S; this is the same car whose visibility made it a doddle to park in town and whose ride, refinement and co-operative auto ’box made a couple of long commutes over LA’s concrete, often static freeways bearable. But although the steering is quick and direct I can’t help wishing Jag had had the balls to go three steps further and give us a really edgy, lightweight special, something closer in spirit to the XK-SS. But that’s not what the brand is about now.

And McQueen might have liked it just as it is. In 1966 he conducted a group track-test for Sports Illustrated, testing, among others, a Jaguar E-type 2+2. ‘I found it very smooth down the back straight at 110mph,’ he wrote. ‘The visibility was good, the brakes were solid. There is great appeal in the 2+2 for the man who will accept a compromise. He can put his two kids in the back, run his wife in the front and take off for his vacation.’

So how good a driver was he? ‘He was better than people knew,’ Derek Bell told me the previous week. ‘He drove that 917 for three months and didn’t crash it, and you know what they were like, so that ought to tell you something.’ Bell spent the summer of 1970 filming Le Mans with him. ‘I think we got to know him in a way few others did, apart from his family. In his other life, everyone wanted to be like him, or be better than him. But when we were making that movie he stepped into our world, and he was modest, and respectful, and unstarry.’

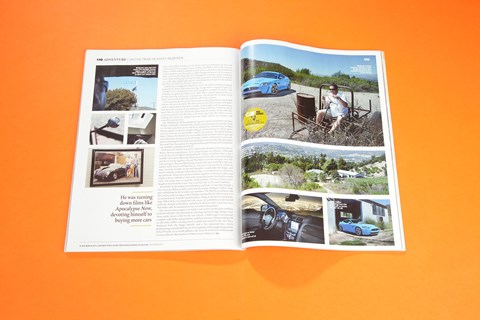

Like Mulholland, McQueen kept moving west, out of LA to Brentwood, then Malibu, and finally to Santa Paula, a small, citrus-farming town 60 miles from LA. He first came here on the trail of an old plane he wanted to buy; he liked the tiny airport so much he bought a hangar, and moved into it with his plane and cars and over 100 motorbikes, and his new partner, the model Barbara Minty. This was his ‘hermit’ era; you wouldn’t think of a bloke with a long beard and a plaid shirt, living in an aircraft hangar with his collection of 10,000 jack-knives as the King of Cool, but he was turning down massive films like Apocalypse Now and Close Encounters, devoting himself instead to flying and buying more cars and bikes, including the XK-SS.

He’d done this before, buying his old Porsche Speedster back from Bruce Meyer, then an acquaintance, now a major-league car-collector. ‘I’d bought it in the late ’60s for fifteen hundred bucks. I knew it had been Steve’s but I wouldn’t have given fifteen hundred and ten for that. We went motorbiking and desert racing together. He and Bud Ekins were the cool guys, but they were nice guys, they just liked being around other guys with bikes and cars. I didn’t really want to sell him the car. I drove it every day but he called me once a week for months. In the end I thought it would make him happy, and maybe someday someone will do this for me, so I let him have it, and not for any premium.’ Bruce has a picture of them together on the day he delivered it back to Steve, with Steve’s famously vicious dog Junior nuzzling his crotch (left). ‘Of course now it would be worth millions. I’d have loved to have bought it back from his estate, but it was the only car his son Chad kept.’

Six months in the hangar was all Barbara could take. In 1979 they bought a tiny, 100-year-old house and 15 acres near the airport. McQueen added a huge grey outbuilding for his favourite cars and bikes. The XK-SS moved here with him, and we park our Jaguar where McQueen parked his for the last time. It is an extraordinarily beautiful, peaceful place, sitting in the lee of a steep dusty slope. When Steve was diagnosed with cancer, he and Barbara were married under the skylight in the house, and when he died less than a year later, on 7 November 1980, his memorial service was held in this garden.

The current owner suggests we might want to drive up the dusty trail that leads into the hills. The trail ends in a clearing, and by its edge slumps a very home-made chassis with two fat rear wheels, a Volkswagen transmission complete with shifter and gearknob, and bent steering column ending with an old white rubber steering wheel cracked and crazed by the sun. Steve McQueen built this buggy himself, and it has remained here, slowly disintegrating, since he died. I try to sit in it; grip the wheel, joggle the gearstick. If that Porsche 911 is worth millions, this must be worth tens of thousands to some collector. But maybe it’s better it stays where it is.