► Tour the world’s greatest Bugatti collection

► Peter Mullin allows us into his rarefied world

► Forget monetary value, it’s so much more

Has there ever been a family quite like the Bugattis? Carlo, born in Milan in 1856, was a 19th century Leonardo Da Vinci, a multi-discipline virtuoso whose boundless imagination and creative fervour found form through hands of extraordinary skill. He designed and made fine furniture, he drew, he painted and he never stopped pushing himself.

At 50 he became a silversmith against the advice of his peers, who pointed out that proficiency requires 30 years of practice. A year later Carlo was turning out award-winning pieces. Son Rembrandt’s sculptures captured the natural world’s wild beauty in incredible bronzes – lifeless cast metal given grace by his preternatural talent. And then there was Ettore, who understandably felt out-gunned at art school and strove instead, together with his son Jean, to blend art and engineering in the finest cars the world would know.

Ponder some of Bugatti’s finest works – the diminutive but dominant Type 35 grand prix car, the otherworldly Atlantic, the monstrous train-engined Royale – and, given their rarity and worth, it’s inconceivable that you might find an example of almost every car in Molsheim’s back catalogue in one place. But in a vast steel and glass building in the Californian seaside town of Oxnard, American businessman Peter Mullin keeps arguably the greatest Bugatti collection in the world, the result of an extraordinary passion for the marque.

Wander inside, at once cursing your dream garage for a painful lack of ambition, and you’re met first not by some wire-wheeled waif of a racer from antiquity but by the bluff, aggressive snout of an EB110, the Gandini-designed missing link between Bugatti in its original form and the VW-funded renaissance that sired Veyron.

‘For me the EB110 is very much a true Bugatti,’ says Mullin. ‘Artioli’s vision to continue the history of the marque in the 1990s with the EB110 was an important chapter in the Bugatti story. He built an extraordinary factory in whichto produce these cars and they were fast – the SS Le Mans was a 600bhp, 200mph car in 1995. I don’t drive it often but every time I do I’m reminded that really fast Bugattis didn’t start with the Veyron.’

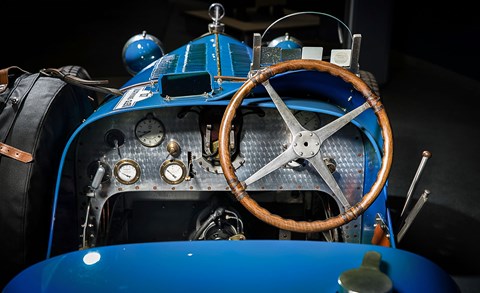

Think Bugatti and you might think Veyron, but chances are it’ll be followed moments later by a mental image of a small but perfectly formed racer in blue with a boat-like body and open wheels – a Type 35. Peter’s is a 1925 Type 35C. It’s driven regularly, on road and track. Conceived at Bugatti’s Molsheim headquarters in 1923, the Type 35 started life as a sketched silhouette, an elegant teardrop Ettore and his engineers then brought to life. (A vast reproduction of that sketch adorns one wall of the current Bugatti assembly facility, the atelier). They did so with elegant design solutions that took existing practices and in most cases improved upon them, all the while clinging to the truth that, on a racing car, simple and light almost always win out.

The 35’s neat suspension arrangement, in which the semi-elliptical springs pass through the axle rather than being U-bolted to it, would go on to become a Bugatti trademark. To reduce unsprung mass the front axle was also hollow – a simple idea fiendishly difficult to engineer. The wheels were striking eight-spoke pieces in cast aluminium, with integral brake drums for faster brake-shoe changes.

The result was a fast, beautiful, agile and – crucially – affordable racer, one that was loved by wealthy superstar drivers and the massed ranks of keen amateurs alike. Initially powered by a single overhead camshaft straight-eight, the early Type 35s were good for 90-100bhp and 115mph. Proudly naturally-aspirated in the face of ranks of supercharged competition (Ettore disliked forced induction, considering it unfair – what would he have made of the Veyron’s massed ranks of turbos?) the Type 35’s speed stemmed from its strong brakes, fine handling and impressive reliability.

Peter’s car was originally a Type 35A, later restored and fitted with a supercharger (Ettore relented eventually…) to create a Type 35C. Pore over the little car and it’s the details that captivate; the lock-out mechanism to prevent the gearbox jumping out of gear on rough roads; the gorgeous accelerator pedal that comprises nothing more than a single large roller bearing on an arm; the brass discs in rows down the side of the engine that you remove to access the valvegear for clearance checks.

‘From a thousand or so races in the 1920s and 1930s Bugatti won 700,’ explains Mullin. ‘It’s hard to think about Bugatti without thinking about the 35, and the Bs and Cs are certainly the best. The 35C’s tremendous competition history makes that car special for me. We’ve had this car apart and what’s amazing is that when you look at some of the engine internals – parts you’ll never see – you notice a beautiful curve. Why do that, inside an engine where no one will see it? Because Ettore said his cars had to be as beautiful on the inside as on the outside, and the fact that other people couldn’t see a part didn’t make any difference – he knew it was there. I love that attitude – he insisted on elegance and excellence throughout.

‘I was an art major in my early years and Bugatti’s thinking spoke to me, in terms of the soul of the man and the way he thought about what he did. I didn’t really appreciate his racing cars’ form until I compared them to their contemporaries. When you do that you see that the other GP cars’ proportions were a little wrong. On the 35 the tail is exactly the right length from the cockpit and it comes to a perfect tapered point, the culmination of curves that start right at the other end of the car, at the radiator grille.’

From the sublime to the ridiculous: the Type 41 Royale. A leviathan at more than 3 tonnes, the 21ft-long super-saloon was powered by a 300bhp 12.7-litre straight-eight engine and conceived, quite simply, to eclipse Rolls-Royce and become the best car in the world. Ettore’s timing couldn’t have been worse, with the car going on sale just as the Wall Street crash and the Great Depression meant even royalty couldn’t afford the Royale. Six were built, three sold and several unused engines went into French rail locomotives…

The Royale in Peter’s collection is on loan from Europe, a temporary monolith among his lithe sports racers. ‘You certainly can’t be neutral to the Royale,’ laughs Mullin. ‘It’s massive. Stand next to it and the tops of the doors are level with your shoulder. It was built for the heads of state, royals and the great families of Europe, but while it’s an incredible piece of engineering it’s not the kind of thing you take out on a Sunday drive. Once again Ettore got the proportions right though – the Royale’s larger than life but visually it works.’

The Mullin museum’s Oxnard facilities are open to the public; the cars on display like an art gallery with lighting, information boards and guided tours. One of the most intriguing displays is of a Type 22 racer in a fairly advanced state of decomposition. With much of it missing and the rest largely rendered in iron oxide, it doesn’t look much. Amazing then to discover that it cost Peter nearly $400,000.

Deliberately sunk in Lake Maggiore following its confiscation by customs officers on the Swiss/Italian border in the 1920s, the tiny Type 22 racer passed into mythology when the chains securing the car in the shallows (its custodian had hoped to let the heat die down before salvaging the car from wet storage) gave way and the car slid to a depth of 173ft. It was discovered by a dive team in 1967, raised in July 2009 and bought in a Bonhams auction by Peter in 2010 for $360,000, a figure well in excess of its original reserve of $70,000-$90,000. The bidding war represented a clash of ideologies – Peter wanted the car to remain as it is; his rival planned to restore it.

Heavily corroded, especially on the right-hand side – the left was buried in the silt and preserved – the car nevertheless bristles with intriguing details; the Bugatti logo on the suspension mounts for the quarter-elliptical rear springs, the myriad layers of paint on the body where this hard-working racer was endlessly re-painted, and mechanical rev counter drive still running from the engine back to the time-ravaged dashboard. Incidentally, a complete, restored Type 22 Brescia can be found on a mezzanine, where two rows of 1920s racers sit looking so elegant you wish racing car engineering had never discovered downforce and wings.

Fascinating though the corroded Brescia is, the star of the museum’s collection has a magnetic draw. The Type 57SC Atlantic’s sheer beauty and affecting physical presence are almost unsettling – the car steals the breath from your lungs and drags your gaze to it. It’s hugely valuable, certainly, but there’s more to the Atlantic than that – you could be ignorant of its worth and still lose hours gazing at its form. Perhaps it’s simply that the Type 57SC might be the most beautiful car ever built. ‘I’m a little biased but for me the Atlantic is the Mona Lisa of the automobile world,’ says Peter, gazing at the car’s almost gothic curves like it’s the first time he’s seen them, not the 500th.

‘There’s just nothing else like it. Sure they’re rare – there are two original 57SC Atlantics in the world – but more than that they’re the epitome of sculptural engineering. There’s real beauty to the riveted metal roofline and fenders but there’s functionality there too. They were used because originally the car that inspired the seams, the Aerolithe coupe, was to be bodied in duralumin magnesium, which you couldn’t weld, so they were going to rivet the panels together. In the end the Atlantics weren’t made of magnesium but the seams and the rivets added flair to the design.’

As quick as it is beautiful, the Atlantic uses a 170bhp iteration of the eight-cylinder (the five exhausts are pure whimsy) double-overhead-camshaft Type 50 engine in a chassis clothed in a body by Jean Bugatti, Ettore’s son. Originally sold to Lord Victor Rothschild, who had the factory fit a supercharger from a Type 55 engine, this car – chassis number 57374 – was rebuilt at Molsheim to correct SC specification in the 1950s, at the behest of its then owner, before being sold at auction in 1971 for $59,000. It was sold again in 2010 for $34 million.

‘I don’t think anyone can look at this car and not be moved by it,’ continues Mullin. ‘From my point of view this car is the apex not only of Bugatti design but maybe of French car design period. Best angle? The rear three-quarter. You see the curve of the roofline, then you see the rear fenders curling around the bottom of the car and back up the other side. That, together with the teardrop roof shape, is about as exquisite as it gets. We’re very fortunate to have it here in the museum.’

Standing among these cars in hushed awe, you can’t help thinking that they must be more spectacular still in motion: at speed in the California sunshine, narrow tyres running fast on hot concrete, mighty old supercharged engine roaring as the slender throttle pedal sinks to the floor. I can only dream: Peter knows. ‘Oh sure, we take them all out pretty regularly – cars are for being driven.’

Some of the museum’s cars are raced, others driven hard on extended road runs. Take Peter’s beloved 1932 Type 55 Super Sport. ‘In terms of sports racers the Type 55 is as good as it gets – I wanted one of these for 30 years,’ he says. ‘I finally found one and it was rare and exceptional: original Jean Bugatti body, chassis and engine. This one is particularly well sorted out. I use it pretty extensively on international events. I took it on a rally in Scotland a couple of years ago, last year it was in New Zealand, and I’ll be taking it out again this year. It’ll do 200 miles a day for a week, no problem. It’s a joy to drive – essentially they took the supercharged Type 51 racing engine, the ultimate, and put that engine in the 55 – I love this car.’ If I had to pick one car, it’d be this one.’

American go-faster tech

Patently not a Bugatti, this Miller Indy special is nevertheless a key car in the marque’s history – hence its inclusion in Peter’s collection. The state of the racing car art in the late 1920s, the Miller was implausibly fast and arrived in Europe in 1929 to smash lap records. It did so successfully at Montlhéry and Monza before being sidelined with mechanical issues – the Millers were front-wheel drive, and their transmissions ill-suited to European circuits. Canny as ever, Ettore Bugatti traded three Type 43 convertibles for the two broken Millers, then the fastest and most advanced race machines on the planet. With the Millers back at Bugatti HQ and in pieces, the secret of their speed was laid bare: the engine’s double overhead camshafts. Bugatti’s DOHC Type 51 racer debuted in 1931, promptly won the French GP and ensured Molsheim’s road cars enjoyed superior performance through the 1930s.

The $40 million star

There are plenty of exceptional cars in the Mullin museum, but gaze upon the Atlantic, restored to its original specification between 2001 and 2003, and chances are everything else will drop into fuzzy insignificance. Impossibly pretty, the Atlantic’s shape reflected a growing interest in the art of aerodynamics in 1930s European car making. The low-slung chassis dropped the centre of gravity and gave the impression the stunning body was barely clear of the road. The low-drag shape gave more speed for a given power output, not that the Atlantic was in any way lacking in poke – its high-compression supercharged straight-eight was good for 170bhp; in 1936!

An interest became a passion, then an obsession’ – Meet Peter Mullin

Being successful in the business of life insurance and annuity has allowed Peter Mullin to indulge a passion for some of the world’s most valuable classic cars. But just five minutes in his company is enough to convince you Peter’s no cold-hearted collector; his passion for Bugattis is genuine and all consuming.

‘35 years ago I became entranced with French cars; Delahayes, Delages, Talbot-Lagos,’ explains Mullin. ‘It started when a neighbour asked if he could have his car photographed outside my house for a magazine. I couldn’t get the image of this car out of my head, its combination of sculptural design and fine engineering, so I bought one.

‘My first Bugatti was a late 1920s Type 37A racer – this was probably 25 years ago – and in the process I learned about the marque’s history, then its all-conquering race success and the fantastic designs Jean created. The passion leads to an interest, the interest prompts you to read and to learn, and in turn the study compounds the passion – it’s kind of an ever-increasing spiral upward. And if you have a Type 37A then you need a Type 35, and then a supercharged 35C, then a 51… and then you’re hooked.

Mrs Mullin’s favourite

The Type 46 was an ‘affordable’ tourer, and Bugatti’s response to the economic crash of the late 1920s. Before Peter bought it in 2001 and restored it, this car lived in Paris, Greece and America. The colours were picked by Peter’s wife Merle, who also chose the trim inside to match her favourite Bottega Veneta handbag.

Praise indeed considering the company it keeps. Thanks to the Mullin automotive museum, Oxnard, California – mullinautomotivemuseum.com

Read more CAR culture features here