► Caterham Sevens: spirit of adventure

► What future in autonomous age?

► Mark Walton ponders the future

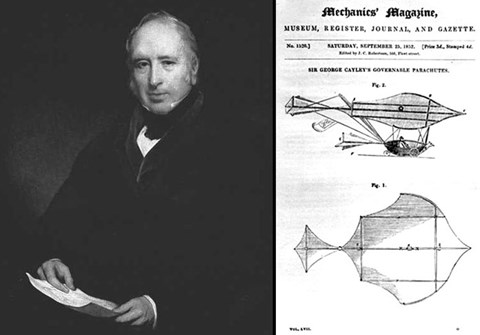

My fascination for the Wright brothers, and those beautiful black and white photos taken on the stark sands of Kitty Hawk in 1903, has led me to ‘discover’ a new industrial hero: a fellow North Yorkshireman called George Cayley. Ever heard of him? Me neither, until recently, which is astonishing – his name should be alongside the giants of the Victorian era, like Stephenson, Brunel and Crapper.

Born in Scarborough in 1773, Cayley was your classic, aristocratic English inventor, a baronet who used his privilege in the cause of reason and science. Cayley was fascinated by flight from an early age, sketching bird wings and developing aerofoil ideas in his school notebooks. He went on to build an early centrifuge, NASA style, to systematically test the forces of lift and drag. In 1799 he laid out the basic principles of the fixed-wing aeroplane – wing, fuselage, tail – and engraved both his design and the forces acting on it onto a silver disc.

But Cayley’s work wasn’t all theoretical. In 1853, the baronet (along with his own Baldrick, an engineer called Thomas Vick whom Cayley kept on his estate) built a glider that looks like a slender rowing boat suspended below a paper aeroplane.

Hilariously, it’s believed either a coachman or a butler became the first to fly in the glider, across a nearby valley called Brompton Dale, as Cayley (below) and Vick watched. ‘Er, are you absolutely sure about this, Your Lordship?’ ‘For God’s sake man, just get in the boat and sit still!’

Cayley’s manned glider was the first significant fixed-wing flight in the world. But more than that, Cayley identified what planes would need in the future to really fly. He worked tirelessly on lightweight materials, inventing the wire wheel along the way (his spokes were made out of string, but he’s the acknowledged inventor of the principle). He also invented the seatbelt; and, incredibly, he developed an early, lightweight internal combustion engine.

Understanding the need for a proper propulsion system (back when dreamers still believed man could flap his way into the air), Cayley dismissed steam engines as too heavy, and started investigating alternatives. In 1807, he developed a working piston engine that used gunpowder for fuel. He came so close to building an actual aeroplane, a century before the Wrights. Cayley was a genius, yet most people have never heard of him.

So what prompted me to think about all this, in this month of all months? A Caterham Seven of course. It’s not quite paper stretched over bamboo canes, but almost. I got to drive the Caterham 310 (below), the new mid-range model with the 152bhp Ford engine, in the middle of winter. No, I didn’t wear a flying helmet and goggles, but everywhere I went, blasting along raucously with the roof down, people stared like I was barking mad.

Read CAR’s Caterham 310 review here

It made me think about a time – coming soon – when electric self-driving cars dominate our roads. Safe, sterile and boring, will there be room alongside them for cars like the Caterham Seven? If so, drivers who cling to noisy internal combustion and manual control will be seen like those early pioneers of flight: wilful eccentrics, with a dangerous passion and a disregard for their own safety (well, in Cayley’s case, his footman’s safety).

The Caterham brings out those feelings – a recognition that what you’re doing is a bit mad – because it’s so crude. It’s a while since I’ve driven one, and all those little details come back – the flappy doors, the canvas roof that’s too small to fit back on. The gearbox whines, and this tuned version of the 1.6 engine pops and coughs its way around town like a homemade experiment, newly pushed out of the garage.

But then there’s the joy, of course. Any Caterham remains an incredible driving experience, with a steering wheel the size of a tea saucer and the jiggling, fingertip sensitivity that feels telepathic. In the end, this new 310 version feels a bit over-grippy to me, with fat Avon rubber but no ludicrous power output to match. It’s fast, but it needs winding up. The entry-model Seven, the skinny-tyred three-cylinder 160, remains my favourite blend of speed and fun – it may not be as quick as a 310, but it’s more satisfying to drive.

Plus, it weighs just 490kg (50 less than the 310). If you stuck wings on that car, it probably would fly. They could call it the Cayley Seven.

More blogs by Mark Walton