► The future of Formula One

► Does F1 need radical change?

► CAR’s Tom Clarkson blogs

‘I don’t even know if we need a cure,’ says Lewis Hamilton. He would say that, wouldn’t he, but the evidence against the sport seems overwhelming: in 2008 the global TV audience was 600 million; in 2013 it slipped to 450 million and last year it dropped to 425 million. That’s a slide of 175m – the population of Nigeria – in just six years.

People aren’t only switching off their TVs; they’re voting with their feet as well. Ticket sales are down at all but a few tracks, scuppering the business plans of promoters because the gate is their only source of income. That leaves the independent races, most of them European – which aren’t government-funded – in precarious positions. We lost the German Grand Prix in 2015; the Italian GP could follow next year and what of Silverstone? The track has sold cut-price tickets this year in order to sell-out, but is that economically viable in the medium-term?

Bernie Ecclestone recognises that something needs to be done. ‘We’ve gone past needing sticking plasters,’ he says. ‘The sport needs an operation.’ But Bernie isn’t willing, or he’s unable, to operate; in chief shareholder CVC Capital Partners he has a paymaster that wants to maximise the return on their investment. They won’t risk anything that will threaten F1’s revenue stream, which was a total of $1.7bn last year.

So how far do F1’s viewing figures have to fall before the sport’s revenues start to suffer? Or how many teams does it need to lose before people believe it’s too expensive? Red Bull are threatening to quit, unless Audi come riding to the rescue as a partner (which Audi sources tell us won’t happen until 2018 at the earliest), and we lost Caterham at the end of last year. Lotus, Sauber, Force India and Manor are vocal in their belief that F1 needs to be made cheaper.

Or are there enough Azerbaijans out there, each willing to pay extortionate sanctioning fees, to prop up the coffers indefinitely? The 2016 European Grand Prix (you read that correctly, owing to a clause in the Concorde Agreement specifying a minimum number of ‘European’ races) will be run just 600 miles from Sochi, through the streets of Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku.

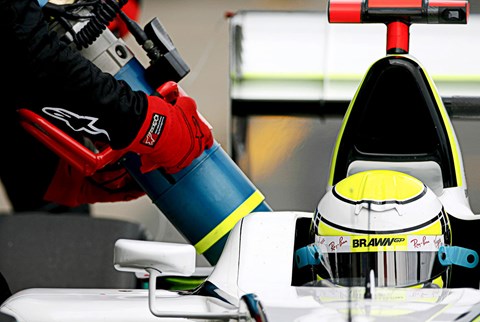

With sponsorship harder than ever to sell, the teams have taken the situation into their own hands. They dedicated their most recent meeting of the Formula One Strategy Group to a rules revolution in 2017. Their suggestions still need to be ratified by the F1 Commission, but the main proposals are as follows: the return of refuelling; wider cars and fatter rear tyres; louder and more powerful engines; improved aerodynamics and more aggressive looks.

‘The idea is to make the cars 5sec per lap faster,’ says Red Bull Racing boss Christian Horner. ‘That would sort the men out from the boys and it would create a big enough differential between us and GP2, who are only 2-3sec off at the moment.’

The sentiment of going faster is one that’s welcomed by the drivers. ‘To go quicker would be awesome,’ says Daniel Ricciardo. ‘It would put us back towards a more heroic status as drivers.’

But history would relate that extra speed doesn’t make more people watch. The fastest F1 cars in recent memory were built in the early noughties, the final years of V10 engines and relatively free aerodynamics. But the era goes down as one of the least interesting in the sport’s history because Michael Schumacher dominated. He won five consecutive world titles and even wrapped up the 2002 title at the French Grand Prix, three months before the end of the season. Audiences outside Italy and Germany struggled.

Now Mercedes are winning everything and the German market has collapsed. There’s no GP this year and terrestrial broadcaster RTL is asking Bernie for more on-track excitement. But it’s a tricky balancing act: F1 doesn’t need more speed at the expense of the spectacle, and nor does it need spectacle at the expense of excellence. That is F1’s USP over a series like NASCAR; it’s about technical and driving excellence. The more contrived you make the racing, the more fans will be suspicious of the sport’s motives. But F1 in its current guise isn’t working. A cure needs to be found (sorry, Lewis).

F1’s six-point crisis plan for 2017. But can it work?

1) Refuelling

Faster cars at the start of races, but potentially more boring racing. The number of on-track overtaking moves doubled in 2010, the year after re-fuelling was last outlawed.

2) Wider cars and tyres

Car width increased from 1800mm to 2000mm, rear tyres widened from 325mm-420mm.

3) Increased aero

Bigger front and rear wings. This will result in more aggressive looks, but would it make the cars too sensitive when following in close succession?

4) Reduced weight

The combined weight of the car and the driver is currently 702kg – more than at any time in recent memory. This reflects the weight of the hybrid systems on the current 1.6-litre power units, but there’s a desire to see the minimum weight reduced to 650kg.

5) More noise, more power

The sport’s four engine manufacturers are working on ways to produce more noise, largely via the exhausts; they also want the 1.6-litre power units to rev higher, thereby producing more power. The Holy Grail is 1000bhp.

6) Driver aids

Anything that makes the drivers’ lives easier will be gone, including power steering. Lewis will need Mansell-esque upper body strength.