► Our original McLaren F1 review

► Roger Bell’s seminal supercar drive

► McLaren’s masterpiece: an archive gem

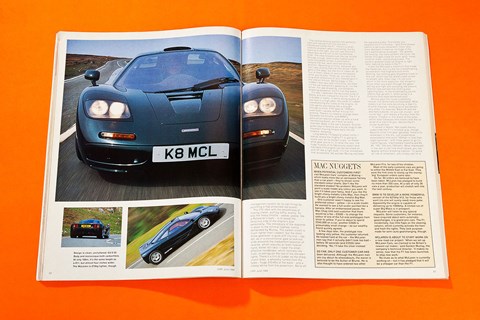

My mind is blown. My soul corrupted. Absolute power has cast its spell. Solo or ménage a trois, I don’t mind. Put me back in the middle, behind the central wheel of the world’s fastest driving machine. I need more, another fix. Two days on the loose in McLaren’s three-seater megacar, and I’m hooked.

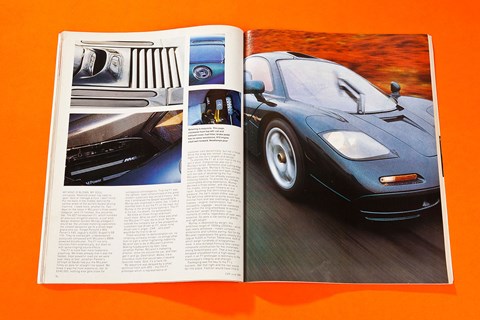

You would be, too. The 627-horsepower F1, which humbles all previous slingshot exotics, is just what design director Gordon Murray pledged it would be: the ultimate motoring experience, the closest sensation to a street-legal grand prix car. Forget Porsche’s 959, Ferrari’s F40, Jaguar’s XJ220, Bugatti’s EB110. They’re overweight, underpowered pussycats compared with McLaren’s BMW-powered blockbuster. The F1 not only trounces them emphatically, but does so with spine-tingling sound effects.

The F1 is more than a hedonistic plaything. We knew already that it was the fastest, most powerful road car we were ever likely to test: Jonathan Palmer’s 231mph at Nardo had put the McLaren firmly on pole for straight-line speed. We knew it was the most expensive, too: at £540,000, nothing else gets close for outrageous extravagance. That the F1 was the lightest, least compromised of the great modern supercars was ancient history. And that it embraced the Gospel according to Murray was engraved in stone, too. It took a talented team to put the F1 on the road, but Murray is the driving force behind it. The F1 is his car, his dream, his achievement.

We knew all these things and much, much more. What we didn’t know was what the McLaren F1 was like to drive. No-one outside the company bar a few prospective customers had driven an F1, never mind driven one in anger. CAR – who else? – would be the first to do so.

There would be no demonstration run, no inhibiting company minder, no strings other than to sign a rather frightening indemnity. My brief was to be at McLaren’s pristine Woking headquarters by 8am, have Jonathan Palmer, McLaren’s marketing director, show me around the car, and then get in and go. Destination: Wales, via a circuitous route that would take in several favourite roads. God, it’s a hard life.

My departure was delayed by a small technical hitch with XP5, the fifth F1 prototype which is representative of customer cars dynamically, but not in finish. While the snag was sorted, I boned up again on the car’s targets and design.

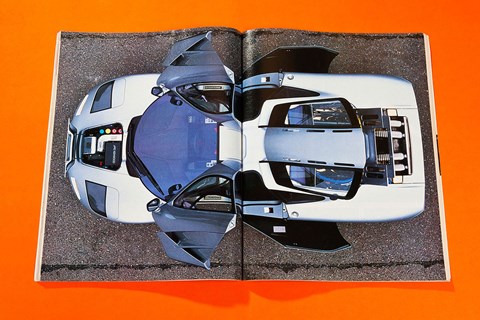

To dismiss the F1 as a rich man’s toy is to sell it short. Compromise was not in Murray’s script. Perfection and cutting-edge technology were. Murray’s 10-hour concept brief in 1990 to the close-knit team charged with the task of developing the first McLaren road car has already passed into motoring folklore. To provide the ultimate uncorrupted driving experience, Murray decreed a three-seater, with the driver in the middle, sitting well forward as in a racer. Anything that diminished driver pleasure, the car’s raison d’etre, was out. The definitive adrenaline pump would have minimal front and rear overhangs, and all its masses – engine, transmission, fuel, occupants, luggage – would be contained well within the ‘dumb-bell’ weight distribution. Low moments of inertia, regardless of load, were essential. So were low centre of gravity and light weight.

Murray is obsessed by weight. His ambitious target of 1000kg (2200lb) – which was nearly achieved – meant compact dimensions and ruthless paring. Not for the McLaren masterpiece the gross obesity of a Jaguar XJ220 or Testarossa, both of which weigh hundreds of kilogrammes more. It also dictated Formula One carbon-composite construction for the immensely strong body/chassis unit. That a test driver escaped unscathed from a high-speed crash in an F1 prototype is testimony to the monocoque’s integrity and strength.

Packaging was key to the F1’s success. Get that right and the rest would fall into place. Fashion would have little to do with the car’s timeless styling. Ground-effect aerodynamics, a cab-forward driving position, spinal air-intakes…these and other considerations dictated how designer Peter Stevens would shape the car. Another Murray edict that raised eyebrows was that there would be no turbo motor. Only the linear delivery of a big, high-revving, normally-aspirated engine would do for a car that was to be the fastest in the world, and civilised with it.

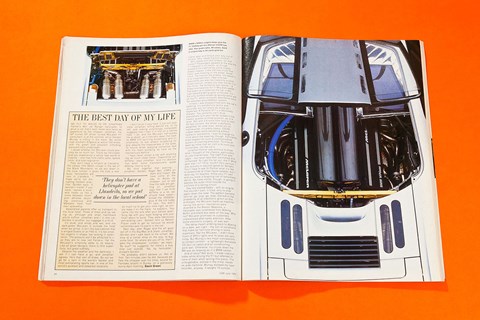

McLaren talked to several engine manufacturers before accepting BMW Motorsport’s proposal to build a 6.1-litre 60-degree quad-can V12. Awesome though it is, this purpose-built 48-valve powerhouse, which yields considerably more torque than a Formula One engine (more than 479lb ft from 4000-7000rpm), draws heavily on existing BMW technology: variable valve timing from the M3 six, for instance. Dry-sump lubrication that reduces the depth of the crankcase squared with the quest for a low centre of gravity.

Drive to the rear wheels is through a slimline six-speed gearbox. There’s no traction control, for that would diminish driver involvement, not to mention add weight. Ditto power steering, anti-lock brakes, and adaptive damping. There’s not even a servo to assist the Italian Brembo brakes – huge, cross-drilled ventilated discs clamped by four-pot callipers. Nothing has been allowed to diminish the tactile relationship between man and machine.

In eschewing modern aids, the F1 is in several respects a simpler, less complex machine than many uprange executive saloons costing a fraction as much. The suspension is essentially subframe-mounted coil and wishbone at both ends, its bushing soft longitudinally (in the interests of ride comfort) and stiff axially (for maximum wheel control).

Jonathan Palmer interrupts my browsing: ‘It’s ready, you can go.’ I sense a twinge of apprehension. Then I recall a Palmer throwaway: ‘Really, it’s just another motor car, Roger.’ Of course it is, I kid myself. Getting into the driver’s seat is certainly not for the elderly or infirm. Push-buttons one the rear wings release the amazing dihedral doors, pivoted on ball-jointed hinges that reflect the wonderful attention to detail evident throughout the F1. Gas struts waft them into the gadfly position where they protrude no further than ordinary doors.

Never mind being after-you polite – the driver gets in first. A handbook picture sequence suggests a bum-leading technique. Palmer favours the single-seater approach: lean back on both arms, swing your legs over the obstructive spar, then do a buttock-launch into the central bucket. It’s an awkward manoeuvre which immediately exposes the main objection to a central driving position: getting in and out. Shutting the door is a little awkward too – a long and fairly strong arm is needed.

Once the driver is in – from the nearside to avoid a nasty accident with the phallic gearlever that sprouts from the offside spar – passengers can step aboard without contortion. As a three-seater, the F1 works brilliantly, not least because passengers are so comfortably ensconced.

At last, I’m on my own in the world’s fastest road car. The slimline seat looks less inviting than the flanking passenger ones, but its embrace is tight, its contours perfect. There’s no power adjustment (too heavy), and the pedals and steering wheel need time and a spanner to alter. Owners get a special fitting. I adjust for reach, strap in (customer cars will get a handier harness) and feel perfectly at ease with XP5’s compromised settings.

There’s nothing intimidating about the straight-ahead controls. Flanking the thick-rimmed Nardi steering wheel are familiar (BMW) stalks for turn/dip and wash/wipe. Tucked invisibly behind is the horn – a pathetic tooter. You’ve guessed: a strident air horn was rejected on weight grounds. Only two of the infra-red’s nine channels are employed. Could a semi-automatic transmission be on the agenda for the other seven?

The rev-counter, black-blobbed at 7500rpm, dominates a light-faced instrument cluster. The speedo is relegated to a small, secondary dial which is so finely calibrated (to 400km/h) – 249mph – in XP5 I couldn’t read it. Other ‘driving’ switches – lights, fogs, spoiler, hazards, screen heating – are within a handspan of the wheel rim. Everything else is deployed on the two carbon-composite spars that flank the driver’s torpedo-tub. Buried down in the footwell, on view to passengers, are exquisite floor-hinged pedals. You could hang them on the wall as engineering art. Let’s go. I turn the ignition key, on the right-hand span down by my shin. There’s a whir of fans, the sound of mating crickets, a brief electronic buzz and lots of flashing red lights – information displays on a small, hard-to-read check-out. All’s well. I fire the engine (foot off the throttle to let the management system do its own thing) by punching a flap-protected red button.

The V12 idles with the smoothness of flowing cream, purring softly, evenly. To blip the heavy throttle – yeeow, yeeow, like a Rottweiler’s bark – is to reveal the ferocious side of the engine’s dual personality. The immediacy of the response is down to the minimal flywheel inertia demanded by Murray. The carbon clutch is much lighter than I expect, but the short-throw gearlever is quite stiff into first – top-left, as in a conventional gate (a lock-out slide prevents inadvertent selection of reverse, which requires an even heavier hand, better still two). I lower the small, effective handbrake, which normally lies flush, to extinguish the last of the red-alert lights. There’s a hint of judder as the sharp clutch bites, a wooshy rumble from the tyres – huge 315/45s at the back – and a classy whine from the powertrain. We’re off.

The central driving position felt perfectly right and natural from the moment I clambered inside the F1. There’s a small visibility problem when overtaking, but by leaning to the right, you can see round it, especially as the car is not monstrously wide. The view over the low scuttle through the huge, electrically-heated (and solar-insulated) screen is panoramic, despite the low, semi-reclined driving position. Reversing is tricky, because you can’t see directly behind (the dorsal intake gets in the way) but the mirror views aft, all four of them, leave no serious blindspots when you’re solo. Three-up, you see only mugshot reflections of your passengers in the interior mirrors. Being piggy in the middle I feel very self-conscious, but then it’s the car that everyone’s gawping at, not the driver. For jaw-dropping, conversation-stopping presence, the F1 has few peers.

It’s late, I abandon the favoured route to Wales and head instead for the A4. The F1 is a doddle in traffic. It skims quietly along at low revs in a high gear, the patter of rubber overwhelming the rustle of the engine, its note gently oscillating like a draught through a chink. Fifth gear at 1000rpm, even sixth, causes neither hiccup nor pinking. There’s no need to change down. Squeeze the throttle, and BMW’s percussion section strikes up with a hard hammering boom, as if an echo from a chamber deep within the car’s bowels. Docility gives way to ferocity as a brutal slug of raw, mountain-moving torque wells the car forward. Amazing.

Long before I’m beyond urban limits, I realise where the mighty F1 is going to score over all its distant rivals: no matter what gear you’re in, or what the revs, the huge muscle of its fabulously potent and tractable V12 engine can be switched on and off like a light bulb. It’s that immediate. No wonder Murray eschews the lag-prone turbo. The harder you squeeze the F1’s throttle – and there always seems to be more movement, more revs, more decibels in reserve, so huge is the car’s performance envelope – the greater the ferocity, the more strident the noise. No Ferrari V12 gets close for aural uplift, never mind for sheer, pulverising power. The world’s greatest road-car engine is right here, behind my back in the F1.

It was the McLaren’s maximum that made the headlines, but it’s the car’s breathtaking acceleration that frightens and thrills. Nothing, but nothing gets anywhere close to this car, which has the world’s best power-to-weight ratio. Even now, I’m not sure which is the more addictive: the slingshot thrust when you slash through the gears, left leg and right arm pumping like pistons, (Palmer had warned that shifting was lightning-fast), or the breathtaking sound effects that go with it, terminating in a Formula One-style demented yowl.

Murray says the yowl is perfectly natural, not technically orchestrated. What makes it all the more enriching is that it’s throttle-induced, lending aural excitement only when it’s required. Back off and the decibels subside, so you can cruise – and cruise fast – with barely a murmur from the engine. Trouble is, the drone of the tyres, which slap Catseyes and cracks with the ra-ta-tat of a machine gun, denies the F1 cruise quietness.

It rained in Wales. Wet roads merely underlined the F1’s colossal grip, though. Beyond initial first-gear getaway, there’s no wheelspin in the dry, just stupendous acceleration that pulls 100mph in less than eight seconds – with three gears to go (in round figures, intermediate maxima are 65, 95, 125, 150 and 180mph). What impresses in the wet is just how much power you can deploy without breaking traction. To avoid all risk of wheelspin, you simply opt for a higher gear and torque your way out of trouble. Who needs traction control?

Who needs anti-lock brakes, for that matter? Passengers gasped at the way the F1 stopped in its tracks, as though arrested by some mighty elastic hawser. Little did they know how hard I was heaving on the pedal. Never mind. The heavier the brakes, the easier it is to modulate them. Heel-and-toe downshifts are also facilitated by a solid brake fulcrum. Unless you look out for it in the mirror, the levitating rear spoiler – a brake and balance foil in McLaren-speak – that pops up to stabilise the car under high-speed braking goes unnoticed. It’s the only surface-breaking aerodynamic aid on the F1, which achieves downforce via a fan-assisted ground-effect system.

Initially, I was disappointed with the car’s steering. It’s wonderfully tactile and accurate, but not nearly as sharp as I expected. A Porsche 911’s is decisively sharper. You certainly can’t drive everywhere with your hands locked in the classic quarter-to-three position, as in a racer. Not with 2.8 turns lock to lock. On fast corners, the wheel is perfectly weighted. On slow ones, worse still on manoeuvres, it’s pretty heavy: 235/45 rubber takes some swivelling around without hydraulic assistance. I was to change my mind about the steering, though. Familiarity bred respect for such a communicative system of unerring precision. To miss an apex by more than an inch is to cuss your clumsiness, not the car’s.

Jonathan Palmer was anxious to know what I thought of the chassis, particularly, its user-friendliness. The ride? Firm and jiggly, but never less than controlled and composed. So I got the tail out, did I? What gear was I in? Third? Fourth? He’s serious. I was actually in second (good for 95mph). You’ll have to ask Dr Palmer what it’s like to powerslide at three-figure speeds, but I dare say it’s feasible. Know your F1 well and you know a forgiving car of fathomless ability. No mere mortal, though, is going to explore the outer limits outside the confines of a racing circuit.

Day two started badly – with an engine that wouldn’t start. It fired, only to stop again down the road. The pattern became familiar: go, stop, go, stop. Alerted to the probability of an electronic glitch on this prototype, the McLaren back-up machine swung into action: mechanics were diverted to the Brecon Beacons, a helicopter was scrambled from Woking. Boffin and black box were on the way. Why not? McLaren promises its customers unparalleled after-sales attention. After some electronic surgery, all was well.

The delay meant ambling back to Woking on a dark, wet night – the sort of conditions that make for hell-hole driving in some supercars. Not the McLaren. I didn’t think much of XP5’s lights and its tyres are very noisy. But Murray’s two major concessions to cockpit comfort – a lightweight Kenwood CD (but no radio) and air-conditioning – work well. Otherwise, my cruise down the M4 was as relaxing as in a BMW saloon.

End of story? Not quite. I made copious notes while driving the F1, but referred to none of them while driving this piece. The unforgettable, etched in my mind, needs no aide-memoire. Murray disliked my tape recorder, anyway. It weighs 10 ounces.

Read more CAR archive content