► A landmark CAR travel tale

► We take a Jaguar XJC down the Danube

► Travel epic from the CAR+ archive

Ian Fraser wrote Destination Budapest! – one of CAR’s seminal drive stories, published in August 1977. We drove a Jaguar XJC down the Danube and behind the Iron Curtain, in the days before the Berlin Wall had tumbled. Read the full unabridged story below.

Although the boundaries are different, Rudyard Kipling’s belief that the twain between east and west would never meet seems as true now as it was when he penned those immortal words. Of course, he could never have visualised that the eastern barrier would start just a few miles on the other side of Vienna, that the Austro-Hungarian empire would be broken and that the concepts of freedom and democracy would be as malleable as an old lump of distorted putty.

At the eastern end of the twain the possibilities of meeting the western end are far more remote than the converse: the society, the economics and the politics see to that. However, the west can go east and, providing you behave yourself, you can steer the reciprocal course at your leisure.

We were told as we filled out the visa application forms that of all the communist-dominated countries in Europe, Hungary was the chosen one. Here, we were told, there was indeed freedom on an unprecedented scale and that the twin cities of Buda and Pest, our destination, were just like any other European city.

Such justification, we thought, had an eerie ring about it, especially as we had recently been told by a Romanian that his country was the chosen one and a Czech of little acquaintance had little doubt that his was the land in which to live. We were not in the position to make country-by-country comparisons, so we simply loaded up the Jaguar XJ5.3C and went to find out about the one that seemed to hold most appeal.

This journey of discovery was to be a two-fold affair: primarily, we wanted to find out as much as we could about the Jaguar, this being the first time we had tackled a very long European trip in the V12 and, secondly, to savour the twain, rather than merely pass through it as we had done in the past en route (by Range Rover) to Turkey.

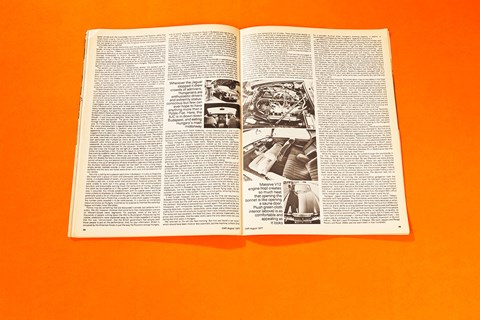

The car intrigued us as much as the destination. Equipped with the new GM automatic transmission and fuel injection, it is in the centre of a trio, or even a quartet, of luxurious (or so the advertisements say) coupes, the self-adored BMW 633 and the Mercedes-Benz 450SLC being the prime contenders, with the de Tomaso Longchamps hovering in the wings as a kind of newcomer waiting for the stars to stumble.

Before we even contemplated the journey, though, we sat down with an electronic abacus to calculate the fuel consumption and the cost based on whatever knowledge we could scrounge about the latest XJ12’s thirst.

However, there was so much duff information floating around, especially in the pages of some of the other motoring publications, that we really wasted our time. Estimates of the XJC’s fuel consumption, both at the optimistic and pessimistic ends of the scale, were wrong and in the event we tended to cover the ground somewhat more rapidly than we had planned, and very much more economically.

Our ‘ideal world’ scheme was to cover the first leg from Dover to Vienna in a day. Travelling three up, with the driving split two ways, the 900 or so miles should not have been too much of a problem.

However, gloomy though the weather may have been in Britain it was diabolical across the Channel. The autoroutes through France and into Belgium and Germany were like Main Street, Venice. Worse still, the Jaguar felt like a rudderless whaler in an ocean of Moby Dicks (otherwise, laden artics).

The 205/70VR-15 Dunlop Sport tyres floated like corks across the top of the standing water: there was nothing to do but slow to a crawl and peer through the windows in the hope of seeing brightening skies. But at least it was a very comfortable way of weathering a deluge.

The XJ12’s appeal in that area was something with which we had become re-acquainted on the gentle run to Dover: the quality of the Coventry suspension, the silkiness of the engine, with its instantly-available power, the equal imperceptibility of the new type 400 GM automatic that at last has replaced the Borg Warner 65 transmission, the tastefulness of the cloth trim and the shaping of the seats.

Above all, there was the lack of noise: nothing from the engine, nothing from the suspension and all but nothing from the wind, and this in a pillarless coupe. But the enormity of Jaguar’s achievement in such a vital area of refinement was not to dawn on us fully at modest British speeds. That was to impress us, and go on doing so, as the XJC whisked us across Europe, sometimes at as much as 140mph, and it was instrumental in driving home to us the real significance of the Jaguar XJ12 in a world of newer, more ballyhoo-ed competitors.

Meanwhile, as we sat out in the rain, the optional air-conditioning (you dial up the required temperature, select automatic and forget it) guaranteed our environment.

Three near-enough six-footers would, if the XJC were a more commonly-dimensioned coupe, spell disaster in a trip fraught with difficult conditions, but we found that the sole concession necessary to satisfy the rear occupant was that the front passenger’s seat needed to be moved a notch or so further forward than the longest-legged among us would normally have had it. Even at that, there was still ample accommodation and at no time during our journey did we ever feel cramped. Headroom was excellent and the seat proportions gave quite fair support, although some additional bolstering at the front of the rear cushion would have been useful.

The Jaguar is one of those cars in which the driving position is not specially demanding, so that the in-and-out adjustment for the steering wheel is of little practical value. Vast improvements have been made in the XJ’s ergonomics since the last time we spent a lot of time with one.

Most of the important minor driving functions are carried out by steering column stalks and the instruments, grouped in front of the driver, are fairly easy to read, but not perfect. In all events, they are an improvement on the days when you had to send your eyes on a day’s march across the fascia in search of the oil pressure, and then turn your left fingers into virtuoso performers across the rocker switches.

The current car’s also have an enunciator panel directly in front of the driver so that any bad news is spelt out in red lights.

The further east we went, the hotter it became. And the more we appreciated the air-conditioning. Despite the simply enormous heat generated by the physically large V12 and the jungle of ancillary equipment packed into such a tight space, little of it soaks back into the cabin and that which may creep in is dispersed by the air-conditioning.

Just how much heat was being generated by the engine struck us every time we raised the bonnet to check the oil – it was like opening the front door of Hades. But the engine was not overheating: we had heard stories of V12 Jaguars operating in the full-throttle atmosphere of the German autobahns overheating at the end of fast runs, so it was good to scotch the rumour, at least in the case of the current injected engine, despite ambient temperatures in the low nineties, and enough of speed to surprise many a Merc, Porsche and BMW.

Nor had the higher cruising speeds had much effect on the fuel consumption. We were regularly reading figures of between 16.2 and 16.5mpg. Remembering that we were running a Jaguar at well over three-figure cruising speeds, this sort of consumption was no less than exceptionally good.

Experience has shown that the much smaller-engined Mercs and BMWs that hustle along the autobahns with considerably more noise, less comfort and nothing like the same power reserves do, in fact, gobble their fuel at much the same rate.

We did encounter one Merc, travelling at exceptionally high speed which, although wearing 280s badges, bore all the hall marks of a 6.9. There is a curious tendency in Germany to either remove the type designations from Mercedes and BMWs or to replace them with badges of the humblest of the species. Thus BMW 528s may wear 520 badges and 6.9s have 280 identification.

We even saw a V12 Jaguar on which the 5.3 had been transposed to say 3.5. Our German informants told us that these little deceptions are due to the fact that businessmen (they are the main buyers of this class of car) don’t want to inflame the workers at a time of high unemployment by being seen to be prosperous enough to be motoring in a fast, thirsty big-engined car.

Having fought their way to the top of the European monetary ladder, there is apparently no way they are going to rock the boat for the sake of a few chrome badges.

This curious over-reaction is a staggering reversal; a few years ago the bigger the badges and the greater the show of success the better. It shall indeed be interesting to see how this game of fooling most of the people for some of the time resolves itself when BMW, for example, start to make their V12. There may well develop a tidy little accessory business to disguise the mobile trappings of success.

We left autobahn system at Regensburg. The headwaters of the Danube, the great river that was to be our constant companion for the next few days, now paralleled the somewhat ordinary road as we aimed south-east for Passau.

Although we were by now getting into the swing of the steering – it’s still very light, at times annoyingly so – the drive-line vibration was nevertheless making us wince. There was nothing obviously wrong under the car and at one stage we had talked ourselves into believing that the tyres, which were running very hot, were flatspotting when we parked to quench both mechanical and human thirsts. The nearest Leyland dealer on our route proved to be in Linz, Austria, where we planned to spend the night anyway.

The last policeman we saw in Germany was standing two feet from the Austrian border. The night air was tropically hot and crawling with insects. He wanted to see the car’s papers and Herr Nichols’ licence. The papers we had; the licence we did not. It was sitting on top of the Nichols’ piano in Wiltshire.

The whole drama reached a sort of lethargic but friendly climax when the policeman decided that phoning England was too complicated (‘I phone, you pay’). Besides, his Austrian counterparts in the border office seemed to be moving into the German’s share of the neck oil as well as their own.

All told this cost about 45 minutes, but it was all quite amiable; I hope that when German tourists leave their licences sitting on the glockenspiel that our police are as courteous. With some final advice about the best eating place on the road to Linz, he saluted us on our way.

But three miles down the road the headlamps failed. Had we been doing 70mph instead of a gentle 45, or had the road been twisting instead of dead straight, what little hair we had between the three of us would have turned instantly grey. Fate, however, had decreed that this incident should take place a few hundred yards from the entrance to a friendly roadside eating and drinking establishment.

The proprietor loaned us his torch (ours, in a fit of temperament had given up) but, as is the way of things in the most inconvenient places, there was no fault to be found. Not only was the proprietor friendly, but his food and his beer were perfect travellers’ fare.

His good advice pointed us a kilometre or so away to a quiet, inexpensive and very comfortable riverside hotel, the Faber-Castell, about six miles from Passau. Holding the headlamp flashers on enabled us to reach this haven.

Austrians take their Saturdays quite seriously. The Leyland dealer in Linz was co-operation personified but this did us little good, since the co-operator was a salesman, not a mechanic.

Mechanics do not work on Saturdays and whatever reason it was that motived one of the dealer’s mechanics to come strolling up in our hour of need, it was unlikely to have been devotion to duty. Nonetheless, he set about wiring the headlamps into the side lamp circuit – an improvisation at best – at just about the same time as Herr Licenceless Editor Nichols’ logical mind worked out that the real cause of the problem was the relay.

With a whoop of condemnation and in the firm conviction that it was Joseph Lucas – the man said by American and European sceptics to have invented darkness – who had sent us plunging lightless through the night, we pounced on the offending relay. But, however we juggled the letters, we could not make Hella spell Lucas. Nor could we transform Made in Germany into Made in England.

Although the spares store was locked for the weekend and there was no chance of getting another relay anyway, we felt immeasurably better armed with the knowledge that our darkness had Teutonic rather than Anglo-Saxon origins.

Had we really persevered in Linz or Vienna we may just have turned up a relay to do the job, but that would have cost us so much time that we opted to aim straight for the Hungarian border and arrive in Budapest comfortably before nightfall.

After our easygoing relationship with the guards on the German/Austrian border, arriving in Hungary was more like the entrance to a high-security prison than to a country. Indeed, had the massive steel girder not lowered so relentlessly behind us as we entered the border area, we probably would have returned immediately to Austria.

Besides being heavily overmanned and incredibly slow in dealing with visas, passports and car documents, every second man had a rifle or sub-machine gun; all the others had pistols. The place was barbed-wire wall-to-wall and as far as the eye could see there was an ominous wire fence separating Austria from Hungary. That a wide stretch behind it is also mined was not in question.

The eastern part of Austria is comparatively dowdy; the western part of Hungary is totally cheerless. The people themselves seemed unsmiling but there was plenty of evidence of hard work in the neat, well-cultivated fields of grain.

Compared with western Europe, traffic was very light, even though our entry point was the main one from the west. A lot of heavy trucks go through here en route to the Middle East and to the other Communist bloc countries, but there were not many private cars. There were a few Polski-Fiats and Ladas, some beat-up old Russian cars plus some East German Trabants, those unstylish two-strokers which, very sensibly, have bodies moulded in something that resembles the material used to make cheap suitcases.

Despite the pounding that the main road unquestionably takes from the wheels of heavy lorries, the surface was in excellent condition, with no ambiguities to confuse visitors.

There could be no confusing that occasional roadside sign that shows a camera with a red stripe through it, either. Only an idiot would take pictures when the sign says you shouldn’t, but these crossed-out cameras certainly draw attention to the fact that there’s something to look at.

Actually, all very dull stuff, like a radio antenna so distant as to be meaningless even if you were an electronics expert, or the entrance to some kind of Russian army camp with its drab grey buildings and people.

After the heavy-handed border activities, we expected a strong military presence right through Hungary, but apart from the occasional truck load of soldiers (usually broken-down) there was little to indicate who really runs the show.

Downtown Budapest is as dreary a looking city as you are likely to find. Make no mistake, though, it was once very beautiful. Even the finest buildings are in a state of decay or total decrepitude. The grime and pollution are chewing their way through the ornate facades and when things drop off no one really seems to care. Of if they care, they are powerless to do anything about it.

The tragedy is that since unemployment is against the law one would think that there would be a workforce available to perform what are basically public works. But apparently not. Everyone in Hungary may have a job, but our observations suggest that only one in three actually has any work.

Budapestians may once have had pride in their city but it doesn’t show now. The streets are wide, tree-lined and could be very attractive. Public transport, naturally, is well patronised and multiple-car trams do good business; so do the little sidewald cafes where people sit and chat for hours in the evenings and at weekends.

As we strolled around that first evening and watched opera goers, unexpectedly formally dressed for the occasion, strolling to the theatre, we also saw a taxi slip through the red light at a steady 40mph or so and miss a trolley car by perhaps a foot.

Driving the Jaguar to some social commitments that evening suddenly seemed like a very bad idea. Better, we thought, to join the taxis than oppose them. When you are in there with the driver you can offer him double the fare to drive slowly and sensibly, which is something you cannot achieve if you are beyond communicating with him.

We pretended not to notice a line-up of temporarily off-duty driverless Lada taxis liked up outside the drunkest-looking bar full of people we had seen for many a long moon, empty barrels stacked outside in their scores. In practice, our plan worked perfectly and the taxis we hailed were driven with care and consideration for our nerves.

Not only is eating out a popular past-time in Budapest, it is also a cheap one. We dined with a group of locals and afterwards went back to the brand new home, in a duplex block of seven, of a journalist. Other inhabitants of the block included a pop star, a script writer and some kind of theatrical producer. We were unable to work out if this group, all basically in the communications business and presumably earning much the same kind of money, arrived at this block by coincidence or if ‘the system’ arranged it for them.

Whichever way it occurred, this hillside establishment with its superb views would be most unlikely to displease its inhabitants who, in the overall scheme of things, potentially wield a lot of influence on the general public.

We noticed that our journalist friend had a Polski-Fiat, a costly car in very short supply in Hungary; the number plate revealed it to be state-owned. In a country as immensely status-conscious as Hungary, it comes as no surprise to find that the really big-league comrades have Mercedes.

Politics may be something that is discussed in private, but certainly not in public. We did, however, discover that some fairly free interpretations are put on Western-based news segments. For example, shots of the tens of thousands of people rushing down the Mall to Buckingham Palace during the Jubilee celebrations were explained away by the simple expedient of saying that this was a ‘rent-a-crowd’, that the British government had actually paid these people to put on the performance. And, for your information, Britain is occupied by the American forces in just the way the Russians occupy Hungary, only far worse. That’s the word from those in Budapest who toe the line.

At least in Budapest, Sunday is taken with a passion. Thus we had something of a struggle to find a petrol station that was open and sold 98 octane. We finally slunk into a Shell fuel station, and took on just a shade less than 20 gallons to enable us to carry out our proposed journey due south, down one side of the Danube and up the other.

By Sunday motoring standards, the traffic was not thick and the variety limited; plenty of suitcase cars and Ladas, a few Polskis and tired old Russian bangers, and a sprinkling of Rumanian-built Renault 12s.

Tourists are not thick on the ground and most of those we did see were from other Eastern bloc countries. We didn’t sight any other British-registered cars, but there were some Finns in a W123 Merc, a few Austrians and West Germans, plus a Chevrolet Camper with a family of you-know-whos apparently taking time off from occupying Britain.

The contrast between Budapest and the countryside is spectacular. While the city once had some style, the country to the south is vast, open and very spectacular – and relaxed because of it.

The villages give the appearance of being basically rundown and populated by old men sitting in the sun watching the world go by, and toothless old women in black carrying the water from street wells. Subsequent investigation in Britain turned up some (pre- and post-WW1) photographs which reveal that nothing has really changed, wars and revolutions notwithstanding.

At last leaving the vast plains of grain, we picked our way up into a little southern village where, quite unexpectedly, the architecture was much more elaborate, almost Mediterranean, and much better suited to the blistering summers. Our map showed that it was possible to go right through this village and further into the hills, but the sticky, uneven bitumen road turned to increasingly rough dirt. We were entering Range Rover territory in a low-clearance, big-overhang Jaguar. We retraced our steps.

These Hungarian country roads were, despite being narrow, perfectly acceptable and the Jaguar’s suspension soaked up the lumps and holes fusslessly. Ours was a sightseeing gait so we merely drifted along through the shimmering heat at 55 to 70mph for the most part. Such a calm pace paid off, for not only was the fuel consumption as low as 18.2mpg but it also enabled us to glimpse some of the fine detail of life in this strange country.

The patient naturalist is likely to find some rare things on these great plains, including an almost extinct type of buzzard. We saw no buzzards, but did see a pair of glorious storks nesting on the roof of an ancient farm building.

No less glorious were the sailplanes at a flying club about 30miles out of Budapest. We sighted them on our return run that afternoon, at a small grass airfield beside the main road. An elderly, de-engined Mig 15 sat on a pedestal at the entrance. The club commandant and a charming multi-lingual woman showed us around, gave us coffee and cheerfully told us of their pleasure-flying activities.

It was certainly one of the best-equipped gliding clubs we had ever seen and it lists in its inventory several powered aircraft in addition to some really high performance sail planes; they also have an excellent motor coach on more or less permanent loan from the makers who are nearby, and a multi-story clubhouse with accommodation and caterings.

But, as with the people on the hill in Budapest, the club members seemed to be the elite, the intellectuals, not the mixed bag that one finds in British flying clubs. As an outsider, one feels that ‘the system’ follows an elitist policy, ensuring that the intelligentsia have too much to lose if they rock the boat.

It was hunger, however, that was rocking us by the time we returned to Budapest that evening. The hotel’s dining room was (mercifully!) closed by the time we arrived, but the staff were quick to recommend some restaurants in the old town. And what an extraordinary contrast again! This proved to be the showpiece, with immaculate buildings, superbly restored and maintained, housing diplomats, museums, restaurants, some shops and a Hilton hotel so craftily built into the old structures (surprise!) that it was virtually unnoticeable.

The restaurant was excellent; the food first class, the service impeccable, the prices very reasonable. And the table cloths were the only clean ones we saw during the time we were in Hungary.

We returned to the old city the next morning. But first we found a car wash which should have been more or less automatic, but the machine, a Mark One Heath Robinson, was temporarily out of order. There were three people on hand to manually wash the XJC but in reality only one girl actually worked and she got the tip, which is absolutely part-and-parcel of any service activity in Hungary, although it was painfully obvious that the two non-workers were also expecting a handout.

The car wash shed adjoined the back of a synagogue, long since disused and falling apart. It will soon become more of an eyesore and dangerous and the locals will want it pulled down: to remove these remnants of former times before they become an eyesore would certainly invite discontent. Leave them derelict and decaying and the populace begin to demand their removal! All part of the master plan.

In daylight, the old city looked no less attractive than we had envisaged is. But it was by then humming with tourists and the purveyors of sob-stories who try to get between visitors and their foreign currency by offering rates far in excess of the going rate.

So great is the need for western currency many of the tourist shops deal only in foreign money and the locals will pay double the official rate to get your dollars, marks or even pounds. Many want it for their now-allowed foreign holidays, for they are not allowed to take many forints with them when they go.

After admiring the views – spectacular to say the least – and the buildings if one can really tolerate the contradiction of a massive parliament building crowned by a red plastic star, we tried another of the restaurants, again with success.

However, the excellent Hungarian beer we sampled just once in Budapest eluded us once more, and we had to settle for a passable Austrian brew. Hungary’s brewing capacity, it seems, is comfortably outstripped by the Hungarian’s capacity to consume it.

Lake Balaton is one of Europe’s largest ponds and a favourite holiday spot for Budapestians. Which explains why there’s a motorway from the city to its shores, and why we chose to spend our last night there.

The hotel, reputed to be the best on the lake, proved to be a high rise affair overlooking the vast waters of Balaton, with pleasant grass down to the edge for sunbathing…and the east European concession for mosquitoes and nocturnal truck noises. While we contemplated the joint problems of noise and insects, Herr Nichols attempted the seemingly impossible: phone call to London. The only certainty was that there was no way such a call would get through before seven that evening; from then on, he was assured, the situation would improve to mere uncertainty.

About 7.45pm, the big moment arrived: they were connecting the call. However, the London number had been confused and Herr Nichols found himself talking to one Judy Rogers in New York, whoever she may be. Fifteen minutes later London was actually winging its way over the telephone wires. An earlier attempt to phone Munich from Budapest had failed, although the hotel’s telex proved to be efficient.

Balaton’s reputation salvaged itself at a local gypsy restaurant, which was able to provide excellent grilled pike, fresh from the lake. The first jug of white wine was insufficiently dry, but that was soon put to rights.

We left early next morning. The sticky glass rings on the tables in the foyer remained where they had been when we arrived. Hot water came out of the taps, though, and the loo didn’t smell even if all the bathroom fittings were rapidly rusting away. A couple of hours and several broken down Russian army trucks later, we were in Sopron, having photographed some picturesque horse-drawn cars, and a steam train on the way.

We exchanged the remainder of our coloured beads for goodies in the local supermarket and aimed for the border. We diverted once more, this time to stumble across and inspect a simply magnificent riding establishment, making itself at home in one of the finest residences in the country.

Those parts the riding school and its collection of coaches are not using is being restored as a museum. Horses are still very much a part of Hungarian country life, a genuine working tool and the stallions at riding school spend a fair percentage of their time ensuring the maintenance of the species – which seems to suit them just fine!

Our departure from Magyarors involved less fuss than our arrival. Nevertheless, it took about half an hour to be processed through. The Austrian border guard, a jovial old soul, glanced at our passports, passed some cheerful remarks about continuing hot weather and wished us a pleasant journey.

We mentally sagged into a feeling of relaxation; the tenseness, the uncomfortable atmosphere that prevails in Hungary takes its toll. Two weeks later, we were still being afflicted by vivid and strange dreams, all relating to the Hungarian experience, and men in dark uniforms with machine guns.

Our departure from Hungary left two other problems. The drive-line vibration was still with us, and we needed to have the relay attended to. But first of all we picked up a BMW 733 in Munich and in convoy set off to find the Leyland dealer.

He was full of sympathy but suggested that we come back in three weeks to have the vibration attended to. Collective dropping of jaws. ‘Ah, but if you had a BMW it would be six weeks. There are a million people unemployed here in Germany, but none of them are mechanics.’

The electrical problem was easier. An imposingly large auto electrical firm, specialising in Bosch equipment, took the situation entirely in their stride, made good the repairs and even put the Jaguar on a hoist to check that nothing was falling off underneath. All this for slightly less than £10! (Meinburk Meineke KG in Seidlstrasse near the centre of Munich, should you ever need them).

While the repairs were being done, we rushed through the countryside in the 733, stopping for lunch at the Herrenhaus restaurant in beautiful Wasserburg: to be highly recommended. By late afternoon we were picking our way out of Munich, bound for Nurnberg.

Heavy rain was making the autobahn slightly hairy and the speedometer suddenly failed. Our Varta Guide was once more proving its usefulness in the quest for a suitable hotel when, just outside the massive Nurnberg stadium, the transmission began making the most appalling clunkings and was obviously having trouble finding a ratio it liked: there was also an ominous grinding noise. The decision was not so much which hotel as where was the nearest one?

In the grey light of morning, the earnest-looking garageman took the stethoscope from his ears and shook his head. He had been listening to the American-made gearbox, with the Jaguar up on a hoist.

‘I think if you go much further, the transmission will seize. On a wet autobahn, you would not like the experience’. Avis had a Rekord at the hotel within the hour and we arrived at Frankfurt in perfect time to catch Pan Am’s world-circling (east to west) flight 001. It was all extremely painless – an attendant from the airport AM’s office came straight up, whisked the car away and said they’d send the bill.

Epilogue

Jaguar recovered the XJC and had it back to us within 10 days, complete with new gearbox. They themselves were bitterly disappointed that the transmission had packed up and I don’t think they believed us when we assured them that we were not upset.

We had done more than 2000 miles in this car and its ability as a long-distance touring car had proved itself beyond question. There simply is no other car that could have transported three people and a considerable amount of luggage so quickly, so perfectly, so quietly, so comfortably and so economically.

In reality the Jaguar XJC 5.3 does not have rivals. Cars of similar concept – some of them cost 60 percent or more – are a pale joke by comparison. As the man in the Leyland showroom in Munich told us: ‘We don’t want Princesses or Allegros. We want Jaguars and Range Rovers and Rover 3500s and we want them in their hundreds.’