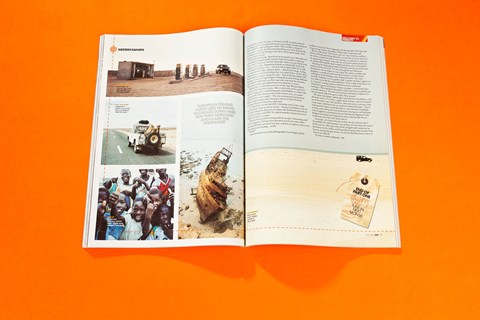

► A voyage of Discovery in the Sahara

► Classic CAR adventure drive from 2006

► Part of our new CAR+ archive service

First, check that it really exists. Second, find out where it is. Then pack your spare undies into a Land Rover Discovery and head off to the Sahara.

I take the warm, saggy teat in my hand, and the camel turns to look at me with a glum expression. Around me the eyes of the desert nomads watch through their headscarves, as a metal bowl is held beneath the udder. I grab the flaccid skin and begin to massage and squeeze, and almost instantly the sound of squirting milk fills the silence. The men’s eyes twinkle. I stand back, triumphant, and the metal bowl is offered to me in a gesture of traditional desert generosity. I look down at the creamy brown froth. There are bits in it. And a couple of fleas. It smells like over-ripe yoghurt and I’ve heard that the camels of the Sahara carry tuberculosis. I glance back up at the expectant faces around me, and realise the word ‘pasteurised’ is never going to float with this crowd.

So I drink. Standing in a camel herd in the middle of the Sahara, with a group of nomadic tribesmen watching my every move, I gulp that camel milk down like warm snot and wipe the froth from my top lip. If I came looking for an adventure, I think I just found it. And then gagged on it.

And of course, I was looking for an adventure: every Discovery driver, stuck in their humdrum domestic routine, dreams of taking their four-wheel drive out on some distant expedition. Fuelled by Land Rover’s marketing spin, we’re told this car can do it all – collect the family shopping in the morning and then escape in the afternoon. From Tesco to Timbuktu, if you like. It’s the kind of journey a Land Rover Discovery always promises. This is the story of what happens when you actually do it.

Like most people, I had to look up Timbuktu on the map. Partly to find out where it is, and partly to confirm it does actually exist – like Atlantis, El Dorado and Camberwick Green, Timbuktu is more a myth than a real place. It all began back in the 11th century, when Arab explorers wrote of the Niger River that appeared to flow east across the Sahara, heading inland, which they assumed was the source of the Nile. They also wrote about a great city on the river, called Timbuktu, full of wealth and riches, a mosque made of gold, great libraries and abundant ivory.

Fast-forward several hundred years, and 19th century Europe was obsessed with Africa, and the source of the Nile in particular. With those dusty Arab texts promising a lost city of gold, the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa (catchy title) set about establishing the course of the Niger, and finding this mysterious Timbuktu. Unfortunately, the first four expeditions sent by the Association disappeared in the desert (spot of bother with the locals), and the fifth, led by Mungo Park, was decimated by dysentery, malaria and tribal attacks. Park reached the river, but the town remained elusive.

As you can imagine, this created a kind of Timbuktumania in Europe, and the newspapers were full of tales of derring-do, adventure, and the awful remoteness of this mythical place. Reaching Timbuktu had turned into a full-scale, Phileas Fogg-style race against time. It was a Brit who got there first, though what Major Alexander Gordon Laing found when he finally reached the town in 1826 came as a bit of a shock. Instead of a beautiful desert Xanadu, he found an isolated little fleapit, with narrow streets, mud huts and murderous locals. Not much gold, no ivory.

But it didn’t matter: the romance of Timbuktu endured. The town came to represent the ends of the Earth, and expeditions always aimed for Timbuktu. If you reached it, you’d got somewhere… even if that ‘somewhere’ was the official Middle of Nowhere™.

And Timbuktu still has that kind of appeal, despite being easy to reach nowadays – I mean, it should be easy to reach: it’s the 21st century, right? Our Land Rover Discovery TdV6 has Electronic Hill Descent, Traction Control, Multi-Functional Terrain Response, and a built-in fridge. Should be a doddle. I tell the family I’ll be gone for a week.

The Discovery is standard, apart from some off-road tyres and a big sliding parcel shelf that replaces the rear folding seats, and has the added advantage of creating a secret underfloor compartment in which we can hide stuff from The Bandits. Ah yes, The Bandits. With Algeria in perpetual conflict, our route will take us down the west coast of Africa, through disputed territory, a couple of ongoing military coups, and large swathes of empty desert ruled by tribal warlords. Gosh.

Another big issue is clothing. I want to travel light – it wouldn’t be right to seek shelter in a Bedouin tent, then unpack suitcases full of flip-flops and Hawaiian shirts. So I go to an outdoor adventure store, and ask if they have any high-performance underpants. Important for any desert ‘insertion’ – ask the SAS. Anyway, it turns out they have: made from pure merino wool, these pants help you to maintain an even temperature, wick away sweat, and best of all, you can wear them for days! So, armed with just two pairs of woollen adventure pants, six jerry cans of sun cream and a new desert haircut, we’re ready. Almost. First we take out the car seats and kids’ toys and biscuit crumbs. Now we’re ready.

On a journey as epic as this, I’m not even going to mention France or Spain – they both flash by in a 48-hour blur of tolls and service stations. Even northern Morocco is painless – the autoroute that sweeps down its Atlantic coast was built in the French mode, complete with tolls and traffic cops. The Discovery demolishes the distance. In fact, it’s almost too good at sealing off the outside world – as we cruise past a huge concrete slum (called Casablanca), populated by kids in rags and millions of shreds of flapping blue plastic, we relax in our leather-trimmed, air-conditioned luxury, effortlessly squishing the miles. By the time we reach Marrakech, we’ve resolved to let in as much of the outside world as possible, by turning off the air con and opening the windows.

This plan has its disadvantages. Heading into Marrakech’s medina (the old quarter), we take a wrong turn and drive into a labyrinth of souks. These covered markets are rammed with people and stalls that spill out into the alleyways; inching under arches and creeping through Moorish gateways, it’s like driving into an Indiana Jones movie. The streets are so narrow, my door mirrors keep bumping leather handbags and knocking rugs off hooks, and I hear through the open window ‘What are you doing? Why are you driving here, tourist pig? You’re driving over my foot!’

So I wind the windows back up.

Fifty miles south of Marrakech, the Atlas Mountains rise out of the dry northern plains. The next morning we cross them at daybreak, crunching up a narrow gravel track, windows down. In the middle of a complex maze of valleys we pass by a Berber village, with houses scattered down the steep slope like a rockfall. The Berbers Africa’s original inhabitants – fled to the mountains when the Arabs came in the seventh century. And just a few years ago, these roads were still impassable with anything but a donkey. Even now there’s no electricity up here, no phones, no cars. We cause a traffic jam when a girl of 10 can’t get her sheep around the car, the track is so narrow. She glares at me. I wind my window up.

Continuing south, the dry scrub of the Atlas foothills gives way to open desert that feels even more forbidding when the sun sets. We reach the coastal town of Tan Tan, and find a small hostel with windowless rooms, sheets with holes in them, and communal showers with so much gunk in the plughole I’m soon up to the ankles in cold grey water.

We leave Tan Tan in an early morning sea fog, and soon cross what would be Western Sahara (if the displaced Sahrawi people won their territorial dispute with Morocco). This land is empty and flat. No trees, no houses, no hills. For a couple of hours we cruise along a straight stretch of barren asphalt, hardly turning the wheel. Then we drive a couple of hours more – 90mph, the Discovery pounding away at the distance. Then another couple of hours. It is unutterably boring. Apart from an occasional 1970s Mercedes taxi with 12 people wedged inside, and one Series II Land Rover pick-up with a camel in the back, the only thing that catches our eye all day is the Atlantic, on our right, glinting beneath an abrupt cliff.

For a country that isn’t even on some maps, Western Sahara takes an awful long time to cross. After a day on the road we’re still in it, stopping in a small fishing port called Dahkla, in a hotel with carpet on the walls and rooms that smell of drains. The next morning we’re back on our biblical, dead-straight road, listening to the hum of the V6 diesel, blinking with exhaustion. Then we lose the GPS. I felt pretty smart at first, using the Discovery’s built-in sat nav – it has an ‘off-road’ setting that allows you to replace the dashboard map with an electronic compass and GPS. Pointless if you’re in Dudley, but here it’s perfect. Until you’re cruising south on an open road with no signposts, and then you glance at the sat nav and notice you’re heading… north! WHAT? I slam the brakes on so hard I almost swallow a sun visor. We’re supposed to be driving south! How did we go wrong? By 180 degrees? When there’s only one road!

But it’s a false alarm. The sat nav can’t ‘see’ one of its three satellites, and it’s confused, poor thing. Bizarrely, it seems the car is lost, but we’re not. After 10 minutes of chaotic map-swirling, we calm down and press on, following the dead-straight road all the way to Mauritania.

Reaching the Mauritanian border will always remain one of the most surreal moments of my life. We drive through the last Moroccan checkpoints, into an empty no-man’s land: the asphalt crumbles and disappears, a couple of tracks lead off to nowhere, and then there’s nothing but wind-whistling, sand-shifting desolation. We crawl onwards. Suddenly, we see a garden shed that appears to have fallen out of the sky. In it, a big man wearing a military uniform beneath a traditional Mauritanian gown (or boubou) stamps our papers. I stand at the door looking in. The wind howls through his shed, which has an old bed and a wooden desk in it.

We rejoin some proper asphalt again and head into Nouadhibou. Like all border towns, it’s a restless, ragged spiral of chaos, a dusty focal point for all the trucks, taxis, kids, donkeys, cattle and carts to converge in the sandy streets. And the taxis are no proud, elderly Mercedes – they’re hand-painted, beaten-up old Renault 12s, with headlights, panels and screens missing, rattling along with no apparent consideration for any highway code. They look as knackered as we feel.

Amazingly, we’ve been away for six days, and not only is Nouadhibou the halfway point in our journey, it’s also where the tarmac finally runs out. After 3390 miles of fast, straight roads, tomorrow we head deep into the Sahara. From here on, our journey gets serious. It’s time for the Disco to show us what it can really do. Also, it’s time to switch underpants.

Digging a car out of the Sahara desert with your bare hands is an unpleasant experience. Of course there’s the heat – an enveloping heat, that radiates from the ground, reflects off the car, and burns, really burns. It’s 43deg C, which makes your eyeballs hiss like fried eggs and your nasal hairs curl. Then there’s the sweat. As soon as you get down on your hands and knees to dig away at the tyres, your body melts with the effort, your face is wet, your eyes are stinging. And the sand – the sand is the worst thing about the desert, which is an issue, believe me. It gets so hot in the middle of the day the sand goes runny like a liquid, making the ground unstable. As fast as you dig it flows back and fills in around the tyres. It gets everywhere; it follows you like a swarm of bees.

And beneath all this discomfort is the low hum of anxiety about where you actually are: lift your eyes and follow your wheel tracks back over the dunes, over rocky escarpments and dry river beds, back to the glinting horizon, and remember you are 300 miles from the point where you turned off the road. Your choices are stark: you either dig, or you die.

Standing on the edge of the Sahara is like looking into a shimmering abyss. The size of the United States but with a population smaller than North London, it’s three and a half million square miles of planet Mars misfiled on Earth. So far we’ve only skirted it. But now we’re going in. Just outside Nouadhibou, Ahmed (our newly appointed desert guide) directs us off the road and into le grande vide, as the French colonialists called it – the big void. Unnervingly, he doesn’t appear to follow any track – it just seems like an arbitrary decision. ‘Let’s turn… here!’ he says, and we do. Ahmed is a Mauritanian, of Moorish descent, and the Mauritanians are nomads at heart. He’s comfortable in the desert, and he really does know where he’s going. Soon after we leave the road we pick up a piste – one of the ancient nomadic pathways which are the roads of the Sahara, sometimes visible, sometimes not. But Ahmed seems to recognise every dune. We make progress. The Discovery is the indisputable Lord of the Desert. After dispatching thousands of miles of asphalt with ease, the Land Rover needs to step up now. First, we deploy the Terrain Response system, a chunky knob behind the gearlever. So what flavour will it be? ‘Rocks and boulders’? Or would sir prefer ‘deep ruts, soft mud and forest tracks’? Hmm, I think I’ll try ‘soft desert sand, beaches and dunes’.

Terrain Response alters the traction control, engine, transmission and suspension settings to get the most out of the four-wheel drive. Does it work? All I can say is, the more you ask of the Discovery, the more awesome it gets. Driving over deep sand is an extraordinary sensation: the motion of the car becomes velvety, like you’re caught in a creamy slow motion – even though the V6 is often revving like a diesel Nascar. But beneath the Disco’s slow speed you feel a physical strength, a bloody-minded determination. And when it does go wrong, it’s all my fault. The sand has an imperceptible crust, and it’s crucial you ride over this to keep your momentum up. I stupidly allow the revs to drop while heading uphill, and we sink into the dune. Then I gas it. We dig in, and after three seconds of wheelspin the car is resting on its axles. Time to get the shovels out.

But it’s not all dunes in the desert – crossing the Sahara reveals scenery as dramatic as Yosemite National Park. We cross wide open expanses, pass under steep cliffs, bump over rock formations that look like dry stone walls, stretching as far as the eye can see. We pass a mountain that looks like a single polished pebble, stuck in the sand, reflecting sunlight. It’s Ben Amera, the world’s second largest monolith after Ayers Rock.

We set up the tents in the dunes and start to cook our dried food, but Ahmed is already in bed – he’s sleeping out in the open, using his robe or boubou as a tent, his precious tea brewing beside him. The desert is silent at night, but sometimes the dunes moan as the wind passes over them. So when I’m lying there at two in the morning and I hear a low noise I sit up. Is that the dunes? But it gets louder, and there’s a far-off, mechanical rumble to it. I hold my breath, straining to recognise the sound. It’s coming this way.

I crawl out of the tent, and in the diffused moonlight run to the top of a dune to see a distant torchlight on the horizon. The light approaches with a growing rattle – it’s a train! But as the single light chugs by, off in the distance, I realise this is no ordinary train – it’s the longest train in the world: bringing iron ore from the mines of Zouerat, in the desert in Mauritania, to the Atlantic port of Nouadhibou 450 miles away. It’s two miles long, with 250 wagons and takes 15 minutes to pass, while I stand on the dune in my adventure pants. An eerie, surreal, encounter.

The railway is proof that even out here, the big void isn’t so empty. The next day we meet nomadic camel herders (and I fulfill a life-long ambition to milk a camel); we drink tea with a goat farmer, whose herd appears to be eating sand; and then there are the isolated villages, single rows of houses populated by donkeys and the occasional Series II Land Rover. In these surroundings, the Discovery looks like a spacecraft, and whenever we stop we have a dozen kids around us, staring in absolute wonder.

The Saharan miles are defeated slowly and methodically, but the road ahead does not look good. The original plan was to cross Mauritania diagonally, to a town called Nema, then cross the eastern border into Mali and on to Timbuktu. Problem is, this border area is notorious for Touareg bandits, who ride out of the desert and steal everything you own. Shortly before we arrive, an Italian expedition is held up. To find out the latest news on the situation, Ahmed calls ahead (some kind of Bandit Hotline) and it isn’t looking good. It seems the army has moved in to crack down on the bandits, aided by the US military. So our route east is blocked. We study the maps, but with Timbuktu surrounded by desert on all sides, our options are limited. We can either retrace our steps, doubling back for thousands of miles to re-enter the desert via war-torn Algeria; or take on the might of the US army; or head south, and then loop north in a 1000-mile detour. We turn south.

Stretching the Discovery to the limit, we drive down into Mali and enter the Sahel, the wetter, greener border region of the desert. Flat out along deeply rutted tracks, through bonnet-deep water, axle-clawing mud, over hundreds of miles of bone-jarring corrugations, we spend 14 hours a day at the wheel to reach the Niger. The car feels unstoppable, but here we learn of a new difficulty: late rains have caused widespread floods across the Niger’s inland delta, and the dirt roads that lie between us and Timbuktu may not be passable.

We stop near the river port of Mopti, in a B&B run by Jutta, a German woman who’s lived here since 1993. She shakes her head when she finds out where we’re headed. ‘You’ll be disappointed,’ she warns. ‘Most people are. People come from all over the world expecting something magical, and find a run-down little town like any other.’ We thank her, but frankly after the journey we’ve just had, Timbuktu could be a phone box and we still wouldn’t care. So Jutta asks around and discovers one road north is passable. After 5300 miles, Timbuktu is now just a day’s drive away.

Arriving by boat is more than I ever hoped for. Timbuktu is all about the romance of exploration, and when we board the small, flatbed ferry the following morning, and cross the slow-moving Niger, we feel just like those Victorian explorers (albeit with air conditioning and a built-in fridge). From the bank of the river we drive the last 10 miles north, and finally enter the gates of our mystical, magical destination: at last! We’ve reached Timbuktu! And wow, what a dump. It really is just like any other desert town – low lying and scruffy, with electric cables and shop signs and rubbish blowing down the street. But after the initial shock, I learn to like this frontier town, with dunes on its doorstep. It is, literally, built onto the desert, with streets and alleyways full of sand. Walk around the warren of mud-built houses in the old town and look inside the open doorways, and you’ll see the interior floors are sand too. Not sand that’s blown in – sand that was here before the houses.

Another striking thing is the mix of cultures and people – you see every tribe, every bone structure, every skin colour on the streets. Timbuktu was always this way: it was created as a trading post in the 12th century by the Touareg, who would come here from the north to trade with the African tribes of the southern Sahel. The Touareg are still here.

Amazingly, the town used to be right by the river, but after a severe drought in 1973 the Niger chose a new course, 10 miles away. Since then, thousands of nomads have moved into the town, swelling the population to 45,000. The wells are now 80 metres deep, and they’re planting vegetation in the dunes to stop the advancing desert. It’s worth trying to save, and Unesco has granted the town World Heritage Site status in recognition of its history and cultural importance. It’s an enigmatic place to explore – we park the Disco, now covered with so much sand and mud it blends in, and thread our way through the filthy, sewage-run streets. Children play amongst the rubbish and the crumbling walls. But the atmosphere is incredible – it feels alien, mysterious, and yes, totally remote.

Remote! After thousands of miles of desert, after floods and dust storms, bandits and border guards, after 12 days on the road and so much sand I never want to see so much as an egg timer again as long as I live – after all this, I’m glad Timbuktu is still so hard to reach. In the 21st century, it means the middle of nowhere is still somewhere special.