► Honda’s innovative founder was a true one-off

► A profile from CAR magazine, October 2006

► ‘Like many geniuses, he was a bit of a nutter’

Soichiro Honda, the man who started the Honda Motor Company and the godfather of the Japanese bike industry, used to switch hobbies like most people flick through TV channels: one after the other, he’d take up golf, painting, skiing, flying. And these weren’t casual pastimes —when Soichiro Honda took something up, he really went to town, bought a golf course, got a pilot’s licence. His wife had to talk him out of pottery, because he wanted to build his own kiln out in the back yard, and she knew he’d soon be running a global tableware factory where the Kai carp used to be. Honda had a restlessly inventive and slightly obsessive mind; like many geniuses, he was a bit of a nutter.

Thankfully for car and bike enthusiasts around the world, Honda invested most of his energy and ideas into engines, not dinner plates —from clunking weaving machines to high-revving motorcycle grand prix engines. And his greatest love — despite the lawnmowers, scooters, generators and powerboats —was cars, always cars. Honda described the moment in his childhood that changed his life forever, when an early car thundered through his dusty provincial village in the middle of Japan. Without thinking, this little boy ran tumbling after it, choking on the dust, enthralled by the noise and the smell. And when it finally disappeared, he dropped to his knees in the dirt beside a drop of oil, and sniffed its gassy aroma. Now, I don’t know about you, but even for a committed car enthusiast, this seems like odd behaviour. But then Honda was more than just a regular car enthusiast: he was a car nutter. And that’s what makes him such a hero.

Genius is always hard to spot before it reveals itself, but with the benefit of hindsight, it can often seem inevitable. Look at Soichiro’s gene pool: his dad Gihei Honda was a blacksmith who was so good with his hands he also fixed guns, made swords and even turned to dentistry when required. After wiping his hands on his trouser legs I imagine. Soichiro’s mum, Mika, was a weaver who used to fix and modify her own loom. Foxy. Which altogether meant that by the time he was five, Soichiro was already making his own toys, and he spent much time with his dad in the smithy, Soichiro soon had the nickname of Black Nosed weasel. How sweet.

It doesn’t end there — to earn a bit more crust, Gihei decided to open up a bicycle repair shop in the village, but there were so few bikes around he started teaching the locals to ride, to drum up a bit more business. Talk about getting on your bike and look for work. Imagine how all this rubbed off on Soichiro.

When the time came for the young Honda to go out and get a job – we’re talking 1922 here, when he was still only 15 – it had to have some-thing to do with cars, engines and fixing things. So Soichiro went to Tokyo, to become an apprentice at a car dealership called Art Shokai. At first he was an apprentice who specialized in filing paperwork and baby-sitting for the boss, but he was soon entrusted with some bug fixing, and his exceptional mechanical skills began to emerge. Fixing the Daimlers and Lincolns of affluent, pre-war Tokyo, he soon graduated to the dealership’s own race car, a Curtiss-engined special, building scratch parts, becoming the ‘riding mechanic’, winning trophies, driving, crashing, and generally having a whale of a time. We can imagine how this rubbed off also.

But it still wasn’t enough for Honda, so when he was just 21 he cut loose and formed his own car dealership. And that’s when he had his first really big idea: he invented a relatively lightweight cast-iron spoked wheel to replace the wooden wheels of the time, and made a mint. Soon Soichiro was riding around town on a Harley-Davison and taking his friends out on his home-made speedboat.

But it wasn’t all rosy. Honda decided his next huge success was going to be piston rings, but his many attempts to fashion a new high performance ring ended in failure. Soichiro came over all moody and obsessive, sleeping in the work-shop, pawning his wife’s jewellery to pay for his experiments. In the end, frustrated by his failure and his lack of basic knowledge, he enrolled — aged 30 — in the local technical college to learn about metallurgy. He was eventually expelled for not taking the exams — in fact he didn’t even take notes — but he wasn’t after the qualifications, he just wanted the know-how. Soon he was selling piston rings to the military, just as a world war kicked off. Awesome timing.

Then, to prove that the act of invention was much more appealing to Honda than mass production, he sold off his piston ring business to Toyota, and spent the war thinking of new stuff. As the Japanese menfolk went off to fight the war, Honda redesigned the lathes in his piston ring factory, so that inexperienced women could operate them. Then he developed a new way of machining aircraft propellers — a hand-made prop that had previously taken a week to make now took 15 minutes. It’s around this time that people started referring to Honda as ‘the Edison of Japan’.

But of course, as we now know, all of this activity and invention proved to be merely the appetiser, the first act, the opening credits to much greater, almost unimaginable success. It began in 1947, when a friend (who knew how passionate Honda was about engines), gave Soichiro a tiny 50cc two-stroke from a redundant military generator. He probably wanted to cheer him up, Japan having lost the war and all that.

Anyway, Honda had a flash of inspiration. Seeing how overcrowded Japanese public transport was at the time, and how fuel was in short supply, Honda decided this would be the perfect engine to attach to a pushbike to get his country mobile again. He lashed up a prototype, using a hot water bottle as a fuel tank, and called it his ‘Putt-Putt’, because of the rather uninspiring sound it made.

Convinced, somehow, that this contraption was ‘the future’, Honda improved the design to create his first vehicle, the A-Type, nicknamed the ‘Bata-Bata’ because of the slightly different but equally uninspiring noise it made.

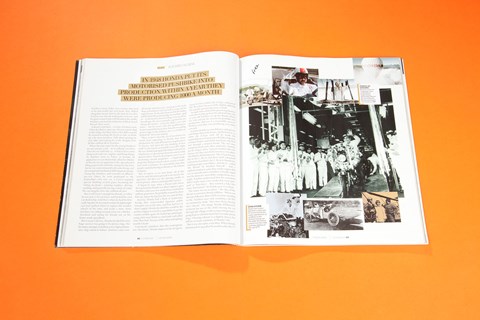

In 1948, with cash from his piston ring business and a bit of a leg-up from his old dad Gihei, the 41-year-old Soichiro set up the Honda Motor Co. Ltd, and put his motorised pushbike into production. And was it a reasonable success? Within a year they were producing i000 units a month.

Soichiro Honda was much better with pistons and things than with money, and he knew it, so when the A-Type took off he made the inspired decision to team up with Takeo Fujisawa, a former banker and timber merchant, who he’d met through a mutual friend. The two men complemented each other perfectly: Soichiro got his fingers dirty, Fujisawa looked after the money, but they were both inventive risk takers who liked to think long term. The A-Type became the B, the C, the D, and then (with a drumroll and crash of cymbals) the E. By now Honda was making proper motorbikes, and the E — called `the Dream’ by Soichiro himself — had a sophisticated new 146cc four-stroke engine that was so smooth and so reliable it virtually wiped out the domestic motorbike competition over-night. Soichiro understood that his customers didn’t really want a two-stroke that went ‘putt-putt’ or `bata-bata’ — they wanted a bike that went `brrrrrrrr.’ So Honda gave it to them.

The name was no accident — the idea of the dream is central to Honda folklore. ‘When you run out of dreams, there will be no more meaning to life,’ Soichiro once said, sounding a bit like an automotive Yoda. ‘One must keep chasing one’s dream.’ The image Honda deliberately conjured up was of the child chasing the car through the village, or the young entrepreneur, going back to school to learn how to make piston rings. ‘Chasing a dream’ is a slightly cheesy, but still an accurate summary of Honda’s life.

But it was also spin, even then. When Honda announced in 1954 that he would tackle the TT – when he hadn’t even been to the Isle of Man – that too was chasing a dream. But it was also a deliberate attempt to occupy the minds of his workforce as the company nearly went bankrupt. Honda and Fujisawa had invested heavily in American and German machinery in the late 1950s, and it brought them to the brink of financial disaster. Then Soichiro invented the 50cc four-stroke Super Cub scooter – a.k.a the Best Selling Vehicle Of All Time (production now at 50 million units since 1958 and still rising). Suddenly everything was rosy again (not least for the worldwide pizza delivery industry), and as if to prove it, Honda actually went on to win the Isle of Man TT, just like he said he would, in 1961. You’ve got to admire his balls.

Bikes, Bikes and more bikes. Bikes dominate the early years of Honda, and growing up in the 1970s, I always thought Honda was essentially a bike company that also made some drab and characterless hatchbacks on the side. But Soichiro Honda loved cars, and in a way motorbikes were just his route back to this first love: bikes were an engineering challenge, a way of making money, but cars were a passion.

The evidence lies in what he produced: the first Honda car wasn’t a ‘putt-putt’ – it was the S500 sports car, launched in 1963 with a double-overhead-cam, four-cylinder engine that revved to an unheard-of 8500rpm. That same year Honda announced it would enter Formula One – this time it wasn’t spin, he just wanted to do it, remembering how much fun it was, back in his car dealership days before the war. Honda was exporting almost 200,000 bikes a year by then, and it had conquered America with its ‘You meet the nicest people…’ ad campaign – he could afford it.

So Honda lined up at the 1964 German Grand Prix with a single car, driven by an unknown American driver called Ronnie Bucknum. Can you imagine a Vespa F1 car, lining up alongside Ferrari and McLaren next season? It was an astonishingly brave move, and in true Soichiro style, the team won its first race before the end of the season, when Richie Ginther was victorious at the 1965 Mexican GP.

Of course, there was a sensible, Fujisawa approach to Honda cars too, and in 1972 Honda launched the Civic, with its CVCC (Compound Vortex Controlled Combustion) engine, a groundbreaking, environmentally conscious step, that met the forthcoming American emissions regulations and established Honda cars in the United States.

Would the Civic have happened if Soichiro had been left to his own devices? Probably not. Like I said, Honda was an inventive genius when it came to carburettors or hot water bottle fuel tanks, but he was also a bit nutty. By the early 197os he was into space travel, visiting NASA and becoming good friends with astronaut and moonwalker Gene Cernan. Then he instigated the Honda Idea Contest, or I-Con, where employees were encouraged to come up with wild and completely useless new inventions — ‘a sports festival of dreams and brains!’ Soichiro called it. ‘We hold I-Cons because it’s fun!’ Mr. Honda told his assembled staff. ‘It also costs a lot of money. So, let’s all work really hard.’ Brilliant bit of industrial relations.

And in the end, his eccentric waywardness — the antithesis of traditional Japanese corporate life — spelt the end for Soichiro’s reign at the head of his by-now giant company. Never mind that he turned up for business meetings in his white overalls; never mind that he got drunk with journalists and told dirty jokes; it was his engineering obsessions that brought him down. In 1968, Honda unveiled a new saloon car, the H13oo, which he had personally overseen. After years of building air-cooled bikes, Soichiro had insisted on air cooling for cars too, and the purity of his reasoning is a joy to behold: ‘Since water-cooled engines use air to cool the water, we can implement air cooling from the very beginning,’ he explained.

But the 62-year-old company president was out of step with his engineers, who knew that water cooling was needed to meet future emissions restrictions; and with his customers, who didn’t want a noisy air-cooled engine. The car was a flop, and his old friend Fujisawa had to ask Soichiro to leave the R&D department alone, and concentrate on being a company president instead.

You can imagine how that hurt this natural-born inventor. So at the age of 66, on the 25th anniversary of his business in 1973, Honda retired, and took on the title of Supreme Advisor. He remained a high profile figurehead, meeting politicians and hugging Ayrton Senna at F1 races, until his death in 1992. But there’s no doubt, Soichiro’s favourite hobby in those retirement years was travelling around, visiting Honda factories, still wearing his white overalls, where he would tell his beloved employees how important it was for them to dream dreams. While they stood there in a windowless factory on the mind-numbingly boring production line gluing grey plastic into Accord interiors. Still, his heart was in the right place.