► Our first taste of Alpine A390

► Alpine’s first SUV is incoming

► Track and skid-pan impressions here

The sun is setting on the sublime Alpine A110, the two-seat sports car that relaunched the brand nearly ten years ago to glowing praise, earning spaces in garages both real and fantasy (my own included) for those who valued its trend-bucking kerb weight.

A replacement for that car is due, but in order to grow, the French maker has its sights set on expanding the range beyond pure sportscars. Firstly, with the Renault 5-derived A290, and then this, the larger five-seater A390.

But electric SUVs like the A390 are rarely svelte, so that’s a problem, even if Alpine asserts it’s a sports fastback and not an SUV. A battery car of this shape does share more with a four-door coupe (albeit a tall one) than an off-roader. But still.

Don’t scroll straight for the comments just yet. Alpine says while it can’t make the car any lighter overall, it can make it feel lighter, by trimming unsprung mass and utilising a clever torque vectoring system to manage cornering inertia. The aim, it says, is to recreate the feeling of the A110 in the A390.

And that’s exactly what I’ve been dispatched to assess. Is the A390 a difficult third album, or another multi-platinum banger?

At a glance

Pros: punchy acceleration, agile and intuitive handling, feels lighter than it (probably) is

Cons: we’ve not driven it on dry roads yet, ride comfort unassessed, can’t comment on the interior

What’s new?

Well in a word, everything, but I’ll get to that. The prototype A390 has some clever innovations to help convince everyone it’s a five-seat A110. Yes, we’ve all heard this sort of thing before when sports car manufacturers go large. And experienced varying degrees of success.

More specifically, Alpine wants the A390 to feature the feeling of agility and lightness, even if it’s ultimately much heavier than the one-tonne sports car. You should be able to shut your eyes and know it’s from Dieppe, and not just because you’ve memorised the smell of the seat foam or dashboard glue they use there.

It’s not certain where in the range it will sit for now – a flagship or a mid-range offering – other than the fact it occupies the “everyday extraordinary” segment. This is separate to Alpine’s “timeless icons” (the A110 and its inevitable replacement) and “racing” (err, the F1 car).

What is clear is the ambition for this car to reel in customers from elsewhere, so it can make some money to reinvest into the brand. Alpine CEO Philippe Krief says think German premium rivals, such as Porsche and Audi, but also Tesla, expanding its customer base in Europe but importantly also Japan and Korea.

What are the specs?

There are few numbers that Alpine is willing to share right now ahead of the A390’s reveal, but we know the car is based on the shared Renault/Nissan AmpR medium platform, with electric motors front and rear, 400v architecture (for now), and a big battery under the floor.

Nothing particularly unusual there, but dive into the detail. The wheelbase is exclusive to the A390, the battery uses a specific high-performance chemistry with its own thermal management, and the (passive) suspension, steering system, and brakes are all unique to Alpine.

It also has three motors, rather than two like the Nissan Ariya Nismo platform mate. It also has a wider rear track – an actual one, not just wider rear tyres. All of this begins to add credence to the assertion that the A390 is its own thing, not a spiced-up Renault or sharper handling Nissan. It doesn’t even use mechanical parts from other Alpine cars.

A couple of systems carry over from the A290 – brake-based torque vectoring and torque pre-control (a sort of pre-emptive anti-wheelspin device), but the larger car also adds all-wheel drive for the first time in an Alpine and active torque vectoring enabled by that pair of rear motors to the mix.

This raises eyebrows immediately – rivals make do with a single rear motor and a clutch pack or differential to distribute torque, but the Alpine’s picked a duo of drive units because they can react quicker (just ten milliseconds in fact) to shape the car’s trajectory in a corner.

The torque split percentages are top secret (because the front motor is used elsewhere, and then we’d be able to work out what the total power output is, which is also a secret) but I know it’s rear biased because they told me, and also it was incredibly obvious from the drive.

What is it like to drive?

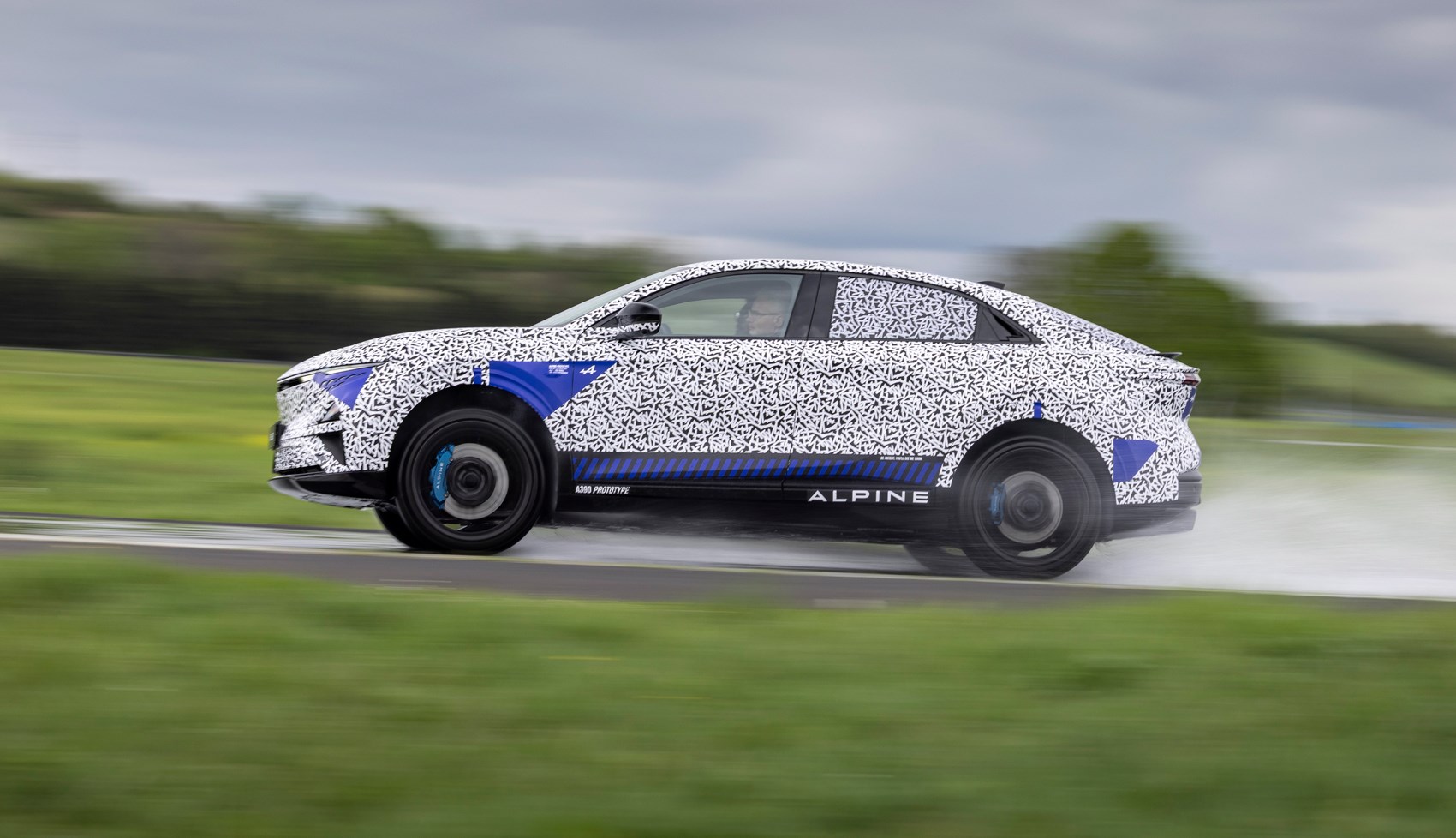

Access to this car has been somewhat drip-fed so far. It’s been driven on snow and ice, and now on the wet track at Michelin’s Ledoux facility in France. A full-friction launch will surely follow after its global reveal on May 27th, but for now I’m testing how well it skids.

But these aren’t just ordinary skids, these are “analytical manoeuvres”, says Alpine, or Business Skids in other words. Driving on slippery tarmac is slightly more indicative than on snow with studded tyres, but it’s still not a dry surface, let alone a UK road.

The wet track opens the opportunity to experience the on-limit handling of the car at a much more manageable speed, in a lower risk environment than for example, a small roundabout in Cambridgeshire. So, I can get a good look at this Active Torque Vectoring and work out whether it’s any good, up to and beyond a reasonable use case.

And spoiler alert: it really is. The car feels poised and up on its toes in a corner anyway, thanks to the low-slung centre of gravity and 49:51 weight distribution, and that balance makes it incredibly responsive to the throttle, whether rotating in response to a mid-corner lift or poke on the exit.

There are two things at work here – the torque vectoring on the rear axle, which is always on, and the stability control safety net that can be tweaked using four drive modes, Normal, Sport, Track and an individual setting. You can’t manually adjust the torque split front to rear and there’s no 100% RWD drift option, as it’s all handled by the drive modes.

Normal and Sport are broadly similar, with the former prioritising stability at the limit and tending to push the nose wide rather than allowing much rotation. Sport slackens things off a bit so you can start to slide the car, and in both cases it’s possible to tuck the nose into the corner with some manageable lift-off oversteer.

Track mode feels much more distinct. For a start the changes to the steering heft and throttle response, and even the brake pedal were immediately obvious. The latter is odd considering the A390 uses a normal hydraulic set up, not the brake by wire system in the A290. Either way, it’s thankfully of a consistent weight, unlike the spongey first inch you often get in an EV.

The power feels more rearward-biased and the car keener to slide around, responding intuitively to my inputs. It communicated its limits well through the sound and vibration from the tyres through the chassis, if not via my fingertips on the wheel, and this inspires confidence.

Up to 100% of rear motor torque can be sent to either wheel (actually 125%, for a complicated reason I didn’t entirely understand) and you can really feel the effect of this in the way the car tightens your line or extends your powerslide depending on what you’re doing with the wheel.

This system debuted on a test mule six years ago, although that car had four electric motors. Engineers concluded they still needed one for each wheel in the rear to get the effect they wanted, but one in the nose (along with brake-based torque vectoring nipping a wheel here and there) did the job just fine.

All the programming has been done in house, and takes into account things like wheel speed, inertia, yaw, and steering wheel angle to understand what the driver wants.

From my experience it works brilliantly, enhancing the driving experience by assisting you rather than misinterpreting impending doom and slamming the throttle shut. In Track mode there is a definite limit of yaw angle before the system starts to persuade the car into a straight line, but there’s plenty of fun to be had in that area before then.

Less is more at this point – too much corrective countersteer (the kind you’d usually dial into a sliding rear-driven car) seemed to interrupt the A390’s train of thought, and pull it straight somewhat prematurely. It was better to relax and, in a way, let the car do its thing first in order to hold an angle.

I later went out with one of Alpine’s test drivers who spent more or less the entire lap sideways with minimal steering input, other than at the initial turn in, to make the most of the Active Torque Vectoring system, which solidified my initial impression.

If you’re starting to bristle at this point, then it’s worth me asserting that we were going really very fast, and there is absolutely no road in the UK where you’d have enough space to drive this sideways – even in the wet – and the commitment level required in the dry would be inconceivable. But it’s an interesting quirk of how the system works in the extreme and worth pointing out nonetheless.

Overall traction levels were hard to assess on the unfamiliar mu of the wet tarmac, but the A390 felt approachable as I nudged towards the point of no return, and adjustable in its angle even beyond. Grip didn’t fall off a cliff either, despite the deliberately short wheelbase offering the potential for spiky, end-swapping behaviour.

That’s certainly true on the larger (forged) 21-inch wheels, which come with Michelin Pilot Sport 4S tyres. These seemed to hook up better than the Pilot Sport EV shod (cast) 20-inch wheels.

The track was much wetter when I tried those (because it had rained) so the difference in the dry might be less obvious. They certainly felt better later on when the rain stopped – the difference between Formula D heroics and aquaplaning on a wet test track can be down to millimetres of water, after all.

Alpine thinks the wheel choice will largely be driven by aesthetics rather than performance potential, and the car’s various systems will work just as well for both, but I’d be keen to try both models on the road before I put a deposit down. Both Michelin options were developed for the A390 and bear a A39 designation on the sidewall.

What’s the interior like?

Shrouded in secrecy (and an actual shroud) for now, but we can tell you about the wheel, which now features an overtake button and recharge toggle that ape the ones Pierre Gasly has in his race car.

Some significant work has been done on the interior soundtrack, which we were able to preview, and on first impressions it sounds quite nice. It’s not a fake ICE noise and there aren’t simulated gear changes like you get in a Hyundai Ioniq 5 N, but Alpine has included some elements from the A110, such as a bassy rumbling sound at low speed.

There are two versions you can choose, and three volume levels (including off) and your preference is memorised by the driver profile, so it’s set and forget. Alpine says it’s reactive to the demands of the driver, rather than just getting louder under acceleration, and each of the three motors was measured and recorded on a test bench so the sound is grounded in reality.

That means there’s more noise when one motor is spinning faster than the others, for example when the active torque vectoring is working its magic, but the noise is not dynamically located. If the rear left wheel is powering you through a huge skid, the overall volume will increase, but it won’t move fore and aft or left and right as this would apparently be distracting.

Before you buy

Not really a huge consideration right now as orders don’t even open until early 2026, but if you’re currently considering a Porsche Macan EV or the upcoming, Neue Klasse-spec new BMW iX3 and you’re not in a colossal rush, it’d be worth waiting to see a full review of this one when CAR Magazine drives the Alpine A390 on UK roads.

Alpine A390: first impressions

Is the A390 a five-seat A110? It certainly accelerates like one and offers the driver intuitive handling at the limit, that rewards you the more you put into it, so from that perspective I’d (tentatively) call it a success.

The all-wheel drive and Active Torque Vectoring system feel like they add control rather than taking it away, so the car feels on your side rather than trying to reign you back in, which is nice. It’s only when you’re sliding it hard on a wet track with the traction control off that it starts to feel a bit unnatural, such as being able to hold it sideways with the steering wheel straight.

But that’s not exactly real-life, is it? So it’s probably not worth worrying about. Where this car will be most enjoyable is being hustled briskly down a country road, and at that point the sensation of all that clever torque-shuffling will melt away into the overall driving experience.

Overall, I found it to be a surprisingly responsive and joyful thing to drive. Will it capture the imagination as successfully as the reborn A110? While that’s not its primary focus, early indications are good.