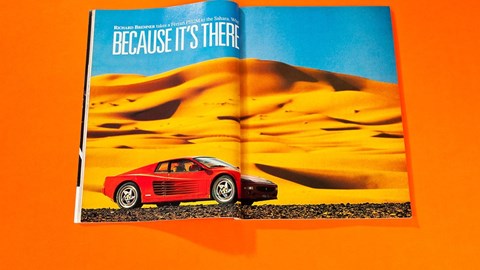

► We retrace our steps to the Sahara, 30 years later

► In a new time, with a very different Ferrari

► Read Part 2 now by subscribing to CAR

For hours we’ve crushed distance with speed, watching in reverential silence as vast landscapes – widescreen valleys between sky-scraping escarpments – slid inexorably from windscreen to windows to rear-view mirror. As coarse tarmac rushed beneath warm Michelins and the V12 cantered just off idle for hour after hour, the effect was hypnotic. There was no traffic; no other life, even. Nothing to break the spell of this elemental place.

Purosangue in the Sahara: the journey begins

Then, perhaps 20 minutes ago, the road turned and made straight for one of those escarpments. It then began to climb, soaring from scrub-flecked valley to cloudless sky in stacked coils of curves. Now the engine is awake. Now the spell is broken. We’ve traded lazy revs and barely-there inputs for 8000rpm and great sweeps of the throttle pedal, a savage sonic barrage and racing shift lights testament to the 6.5-litre V12’s reach and potency.

What’s more, the rest of the Ferrari’s powertrain – an eight-speed twin-clutcher with shifts like a GT3 car’s and dexterous, apparently unimpeachable four-wheel drive – is offering no real counter-argument to this hedonism. A gearlever, three pedals and just the one driven axle to manage? For better or for worse the Purosangue cares not for such impediments to speed. The contrast in effort, on the car’s part and mine, between now and just a few moments ago is, like the Ferrari’s crimson paint against the scree, stark.

Three quick inputs have swapped Comfort/Soft for Sport/Hard and Sport ESC, and now the Purosangue’s brutal brand of athleticism is vindicating the decision to come here in spectacular style. Just as your brain grows uneasy, its calculations around speed and mass and the severity of the upcoming curves prompting a fast-swelling sense of fear, the Ferrari’s composure crushes the nascent panic.

The firm and powerful left pedal (in drilled aluminium, naturally) is endlessly reassuring, the very physical deceleration it delivers instantly erasing any excess speed your wanton V12 usage may have brought about. The steering, so slack-free and responsive you must, like a sniper, measure your breathing and consciously moderate your inputs, appears able to send that long, heat-weeping bonnet arcing wherever you choose regardless of speed. And, thanks to those hypnotic hours that came before, the Purosangue and I feel less like two forms working together than one without demarcation; decision-making organism and physics-stretching machine as a raging singularity between shimmering armco.

Then a very strange thing happens. Mid-corner, braced against the Ferrari’s unwavering body control, I think about a desk and a telephone and a call nearly 30 years ago; the beat of a butterfly’s wings and a chain of events that made this drive, this moment, inevitable even then. Rounding one corner I see a mountainside much like every other. Only this one is different, familiar. Not from a dream or a previous visit but from a page – a spellbinding image, powerful with incongruity, in which a scarlet 512M speeds along a road cut into a rock face.

The road has changed, sure. But this is the spot. Where once it doubled back around each and every crease in the topography, struggling to make genuine, crow-flies progress, now the highway, smooth as glass, runs right through the ridgeline in a cutting 80ft high. But look for it and you can see the old road, blocked off and obsolete. My world, deafening as it is with an engine and chassis under considerable load, grows quiet for a moment, the better to hear what I swear I can hear: a flat-12, an open-gate manual and three pedals working their way east three decades ago.

How it began the first time

Two Ferraris, 30 years apart. But so insignificant is the time between them that, so far as this landscape is concerned, ancient, unchanged and sentinel, they might be the same car moments apart, their 12-cylinder cries echoes of one another in eternity.

‘I can still see the desk and the phone,’ says Richard Bremner, architect of Ferrari to the Sahara the first time around.

Richard joined CAR in 1985. The following year he went to Morocco to drive one of the first UK-built Peugeots, a 309, to see if it was at home in a country then, as now, stuffed with old Peugeots, a legacy of Morocco’s French colonial rule. Richard was struck by how open and empty the roads were, how beautiful the country was and, pertinently, what an amazing place it would be to bring a supercar. For that poor 309 spent an awful lot of time going as fast as it possibly could, speeding rim to rim across flat-bottomed valleys devoid of a single soul. All of which got Richard thinking.

Fast-forward to 1994 and Bremner, sitting at that desk, picks up that phone and makes that call. Now, CAR had a good relationship with Maranello – it had pulled off the first F40 versus Porsche 959 twin test – but this was a huge ask. ‘Leave it with me,’ said the man from Ferrari, Antonio Ghini. A few days later he called back. So long as Bremner was sure he could get unleaded petrol (he was; he’d spoken to Shell) then the answer was yes. I mean, can you imagine?

Timing is everything and Richard’s was exquisite. Ghini had an ex-engineering 512M kicking about. He’d been thinking, too, about how bland and samey Ferrari stories were becoming. Maranello was also keen to address the misconception, exacerbated by the tiny annual mileages most owners did, that its cars were fragile. Then came the call from CAR. Bremner had his Ferrari.

Legacy

Its exquisite timing also helps explain the story’s enduring legacy. The year 1995 pre-dated the proliferation of both internet access and mobile phones. It was the calm before the online, endlessly connected storm, and perhaps the last time in human history you could take a Ferrari somewhere and reasonably expect that people wouldn’t know what it was.

While some in the CAR office were uneasy at bowling into what wasn’t a wealthy country in a millionaire’s car, Richard had a hunch the 512M was more likely to provoke excitement than resentment. So it would prove. Only a pair of teenagers in Marrakesh knew what the car was, asking if it was Ferrari’s Diablo riposte. It was. For many Moroccans the Ferrari was as alien and unknowable as a land-bound UFO, and Bremner’s story pulses with that wide-eyed wonder. With faultless logic one even asked if, given that in his experience cars had one exhaust pipe and one engine, did the 512M’s twin pipes denote two engines?

Much has changed since 1995, not least at Maranello. In the ’90s Luca di Montezemelo was busy dragging Ferrari from unprofitable antiquity to something approaching modernity. The F355 and 456GT were both paradigm-shift cars launched early on his watch. Modern Ferrari, complete with an official dealer in Casablanca, is a success story built on shrewd management, savvy commercial moves and that wildly successful stock-market flotation. Revenue in 2022 was a touch over €5bn with 13,000 cars sold. And in late summer 2022, after years of conjecture, Maranello pulled the covers off the Purosangue, its first four-door and the first car in its history not to sit as low to the road as was practicably possible.

Echoes of the past

Nearly 30 years on Ferrari is still here; still making stylish flagships with extravagant engines. And still saying yes.

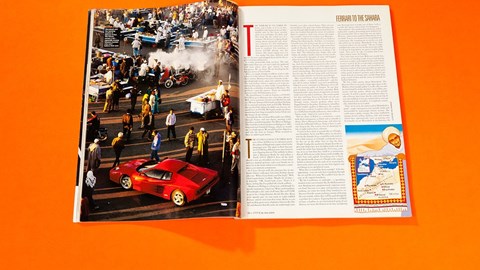

No faster than shifting tectonic plates the ferry drops its twin ramps and, with one almighty clang, sets us free – free to drive into Africa.

On the dockside, chaos. In the Ferrari’s sumptuous cabin, calm. Despite sharing a hold with idling refrigerated trucks for the last couple of hours the car’s display indicates a decent level of air quality. Fully fuelled, the read-out shows some 370 miles of range (we’ll average 17mpg). And the fierce drop-off from the ferry ramp to the dockside holds no fear in a car with plenty of ride height, not to mention a body-lift function should we need more. Doing the same in a Ferrari supercar would be slower, more stressful, scrapier. (In ’95 customs officers went at the 512M’s sills with a screwdriver with such fervour Bremner feared having to find a panel beater to put right the damage; three decades on we’re harmlessly X-rayed and sniffed by dogs.) There is, it turns out, nothing remotely slow, stressful or scrapey about the Purosangue.

This stretch of motorway south from Tangier to Marrakesh is Morocco at its most developed – nearly 400 miles of immaculate, toll-maintained motorway with Shell , McDonald’s and Burger King. You could be in Spain but for the currency and the signs, many of which show place names in Arabic and Tifinagh, written Berber.

When CAR came in the 512M only a fraction of this road was motorway; a single short stretch just north of Marrakesh. My illustrious predecessors decided to celebrate with a brief 150mph squirt, to better hear and feel the flat-12 uncorked. That twilight speed run nearly ended abruptly against the back of a dawdling, unlit dump truck, and 30 years on this still isn’t a great place to extend a 12-cylinder Ferrari… Immaculately uniformed officers hang out at every toll stop, and less than two hours after landing I’m being beckoned into a van for a little chat…

A minor set back

The charge? That’ll be 130km/h in a 120km/h limit. The evidence? A crystal-clear shot of the Ferrari’s prow, apparently moving through the warm Moroccan air with excessive speed. The image is so sharp you can see the handful of Haribo Starmix going into my mouth. The punishment? A 150 dirham/£12 fine. I have no cash.

My cop shouts to his partner, presumably asking after their card machine. His colleague saunters over and, as he gets closer, breaks into a broad grin. He says something and laughs. Now my friend is laughing too, chuckling so hard tears prick his eyes. ‘We cannot fine Mr Bean. Welcome in Morocco Mr Bean!’ This face may not open doors but it can, it seems, quash speeding tickets in Africa.

Marrakesh

The transition from cruise-controlled, calm-as-a-cucumber motorway to fire-and-brimstone Marrakesh is as abrupt as it is violent. (If only finding cruise control was more straightforward. Its touch controls, which call the left steering wheel spoke home, remain unlit and mysterious until you wake the system – not always easy with the haptic controls’ fickle temperament.) The city is neither particularly large nor difficult to navigate. But its fortified core is as perfect a barrier to the peaceful progress of vehicles as it’s possible ⊲ to imagine, certainly those with four wheels – the packs of scooters move easily like shoals of fish on unseen currents.

From the motorway you can effortlessly lap the city on a ring road of broad boulevards. But if you want to see this place properly, to feel its energy, then you need to push into its cramped centre.

Into the city

That starts with archways barely wide enough for the Ferrari’s mirrors, and into which you must simply force yourself: two-way traffic and a portal big enough for one car simply doesn’t work otherwise. Timidity is punished with a conspicuous lack of forward progress, the traffic behind you building exponentially, in both quantity and ill-temper, as you wait. In a Ferrari on Italian plates we’ve no chance of blending in. But drive as everyone else drives – positively, decisively, forcefully, even – and you can at least move with the storm, like a galleon with sails and anchor stowed. And that is infinitely preferable to pitching yourself against it, a sure path to tears and pain and mangled aluminium.

This, Morocco’s fourth largest city and one of Africa’s very busiest, is not a place to drive windows up, stereo on. Let it in. It’s late afternoon now and the city’s dusky pink walls are by turns cool and muted in the shade and hot-ember warm in the dying rays. Smoke is ever-present, the aromas bringing on painful hunger pangs for anyone with an empty stomach. Blue-grey two-stroke fumes hang in the air like incense. Donkeys and camels jostle with the mopeds and the minivans amid an endless stream of Dacia taxis.

The chatter of conversation, the cries of the hard-working hustlers, parping horns, squealing brakes… Driving here is, according to the internet, the stuff of nightmares. In truth it’s special, as memorable as California’s Pacific Coast highway or Italy’s Amalfi coast, just in a very different way. In 1995 the 512M picked its way through to the bustling main square, Jemaa el-Fnaa, with its snake charmers and food stalls, but that’s off-limits these days, a prized machine calibrated for the efficient extraction of tourist dirhams.

In this labyrinthine city the Ferrari helps and hinders in equal measure. Visibility is a mixed bag. Yes, the driving position is elevated versus every other Ferrari in the company’s 75-year history. But you can’t see much out of the back and that endless bonnet creates a faintly terrifying blind spot on the far side of the nose. At least the effortless steering and superb brakes are on your side, as are the hard-working blind-spot assists on each side mirror and the parking sensors, all of which work overtime as you try to tease what isn’t a small car (just over two metres wide, a smidge under five metres long and 1.58 metres from floor to carbonfibre roof; a panoramic glass roof is an option) between boundaries defined organically, over centuries, by the movement of smaller, squidgier objects.

In the cool, dark calm after sundown the Ferrari and I gaze longingly at the map and at the mountains to the south, silhouetted against the twilight sky. To date the Purosangue’s proved almost faultless. But you don’t bring a V12 Ferrari all this way to cruise motorways and battle through cities. We need a road worthy of the car. In the majestic Tizi n’Tichka, the mountain pass that corkscrews up to an ear-popping 2200 metres between savage slopes and snow-dusted peaks, we’ll find it.