► In 1990, the BMW M5 was the world’s fastest saloon

► The BMW was as fast as a supercar, but did it feel as special?

► CAR pitted it against the Ferrari Testarossa to find out

BMW has just launched, in Britain, the fastest saloon ever made. The new M5 can accelerate as briskly as most mid-engined supercars, could do a genuine 170mph if it were not for a speed governor, and can lap racing circuits more energetically than just about any road car, period.

It’s a pukka supercar. The only difference is that it has four doors, while supercars tend to be long, low and mean, have two doors, and be high on panache but low on practicality. The M5 is a road racer for all the family. It can meander around town, four-up, with all the decorum of a Ford. But can thunder along open roads with all the venom of a Ferrari.

That’s the theory, and BMW’s boast, at any rate. To find out if a car designed for passengers as well as drivers really can involve, and please, the enthusiast as much as a blood-red Ferrari, we tested one of the first right-hand-drive M5s to arrive in Britain — yours for £43,465 —against Ferrari’s top-of-the-range super-car, the Testarossa (£106,998, but subject to a four-year waiting list, and particularly greedy second hand dealers).

Not only is the Testarossa Ferrari’s most expensive production model, but it is surprisingly practical — for a mid-engined two-seater, at any rate. Mindful of some of the mindless millionaires attracted to the marque, Ferrari deliberately engineered the Testarossa to be ‘user friendly’. It is noticeably less intimidating to step into than its predecessor, the Boxer, or any other 12-cylinder Ferrari berlinetta. You feel as if you’re in a road car, not a space capsule.

Is it more invigorating than BMW’s best sports car (which just happens to be a saloon)? And can a ‘sensible’ Ferrari possibly be better all-round than the M5?

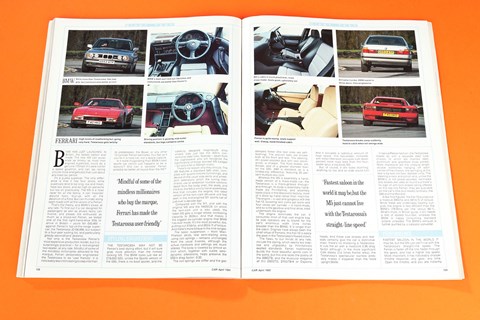

The Testarossa may not be Ferrari’s best styling effort, but it will sure grab more attention than the homely looking M5. The BMW looks just like an £18,000 520i. Unlike the Sports version of the 535i, there is no boot spoiler, and the carefully designed magnesium alloy wheels look just like the 5201’s conventional steel rims. Nobody — apart from the cognoscenti who will recognise the significance of those discreet M5 badges — will pick it for a 155mph motor.

There’s no reason why they should. The M5 features a standard 535i shell, complete with quaint chrome furnishings, and devoid of the usual side-skirts and wheel-arch extensions which the tuning merchants use to embellish humble saloons. Apart from the body shell, the seats, and the trim, the M5 is wholly hand-assembled. And that includes the engine, the latest version of the twin-cam 24-valve unit first seen in the mid-engined M1 sports car of just over a decade ago.

Compared with the M1, and with the original M5 and the M635CSi (in which the twin-cam unit is also used), the latest M5 gets a longer stroke, increasing capacity to 3535cc. And that makes it the biggest six-cylinder engine that BMW has ever made. It’s the most powerful, too, putting out 315bhp, and 265Ib ft of torque. And there’s more torque in the mid-ranges.

The basic suspension — front MacPherson struts, rear semi-trailing arms using coil springs — remains unchanged from the usual 5-series, although the actual hardware and settings are much altered. The body is lowered by almost an inch which, together with subtle aero-dynamic alterations, helps preserve the 535i’s drag factor: 0.32.

The coil springs are stiffer and the gas dampers firmer (the rear ones are self-levelling). The anti-roll bars are thicker both at the front and rear. The steering, still power-assisted (but with less assistance), is sharper. The front brakes are thicker, and of a greater diameter than on the 535i. ABS is standard, as is a limited-slip differential, featuring 25 per-cent multiple-disc lock.

Whereas the M5 is essentially a hand-made version of a mass-made car, the Testarossa is a thoroughbred through-and-through. Its body is essentially hand-made (by Pininfarina), and assembly takes place in the Maranello factory, most of it done by hand rather than machine. The engine — a vast and gorgeous 4.9-litre flat-12, boasting twin cams per bank and four valves per cylinder — is hand-made, and so is the gearbox and final drive, sited underneath the engine.

The engine dominates the car. It consumes most of that vast engine bay. Its side radiators are to blame for the car’s enormous width (nine inches broader than the BMW). It is longer than the cabin. Engines have always been the chief virtue of Ferraris; this flat-12 is easily the jewel in the Testarossa’s flawed crown.

The flaws, to our minds at any rate, include the styling, which seems too slab-like and ungraceful by Pininfarina’s exalted standards. Ferrari traditionally builds the most beautiful sports cars in the world, but this one lacks the poetry of the 328GTB, and the muscular elegance of the 250GT0, 275GTB/4 or Daytona.

And it occupies a ludicrous amount of road space: this two-seater, complete with mean little boot, occupies over seven percent more road area than the four-seater (plus a big boot) M5. But, of course, it still looks stunning: anything so low and so wide would turn heads. And those side strakes and rear slats certainly give the car a distinctive mien: there’s no mistaking a Testarossa. It cuts the air with a mediocre 0.36 drag factor although, in the more significant CdA stakes (Cd times frontal area), the Testarossa’s spectacular lowness probably makes it slipperier than the more upright BMW.

In typical Ferrari fashion, the Testarossa makes do with a separate steel tube chassis, to which are married steel, aluminium and glassfibre body panels. More impressive are the unequal-length double wishbones hanging off each corner of the chassis; the springing at the rear is by twin coil/twin damper units. The steering is rack and pinion and, unlike the BMW’s, is not power-assisted. Ventilated disc brakes are used all round but there’s no sign of anti-lock brakes being offered on this top-line Ferrari: they are available on the car’s little (but newer) brothers, the 348 and the Mondial.

A few final figures: the flat-12 pumps out a massive 390bhp and 361lb ft of torque. While these are undeniably healthy out-puts, the engine is less efficient than the BMW’s (78.9bhp per litre versus 89.1). What’s more, in British guise, it still needs a diet of leaded four-star, whereas the BMW is happy consuming standard octane unleaded. The BMW’s exhaust is further purified by a catalytic converter.

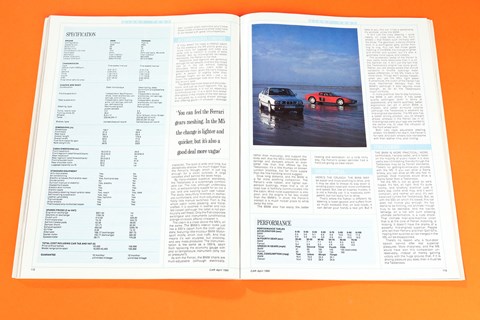

Fastest saloon in the world it may be, but the M5 just can’t live with the Testarossa’s straight-line speed. The Ferrari is faster off the line, faster through the gears, and has a higher top speed. More important, it has noticeably sharper throttle response, any gear, any time. Open the throttle, and you are instantly rewarded with a surge of power: whether it be a tempting morsel (to accompany small throttle variations), or a lusty plunge, The Testarossa’s engine is wonderful. It is in a different league from the BMW’s motor, marvellous though that is.

Figures taken at the Milibrook proving ground in Bedfordshire underline the Ferrari’s advantage. It was wet when we did our testing, but the Testarossa still surged to 60mph, from rest, in 5.8 seconds, 0.7 seconds better than the M5. You can knock half a second or so off those times in the dry. To 100mph from rest, the Ferrari scored 12.2 seconds, to the BMW’s 17.5. It’s the difference between being massively fast, and being very quick. The Testarossa’s advantage is just as pronounced in the fourth-gear figures, useful as a guide to overtaking times. You’ll have nipped back into your lane in the Ferrari, while the BMW is still on the wrong side overtaking the lorries.

In terms of top speed – irrelevant in Britain even- more than it is in Germany or Italy – the Testarossa also scores, with a claimed (and believable) maximum of 180, compared with the BMW’s governed 155. Either car is quite fast enough for plying motorways, although the M5 covers the ground with far less fuss, and demands much less input from its driver. The Ferrari not only is faster; it feels much faster. Its engine always seems eager to go, to punch you in the back. It feels brawny from under 2000, and delivers a massive wallop when the tacho needle starts to swing through the central part of the gauge. It revs smoothly, musically, and ebulliently to its red line – a surprisingly conservative 6800rpm. It feels as if it could go much, much higher.

The BMW, frankly, doesn’t feel as fast as we had expected. As with the 535i, the M5 is overgeared for speed-restricted Britain, and the engine, strong though it is, can’t overcome the long-leggedness of the car. In fourth gear with a couple of thousand revs up, this BMW supercar feels positively languorous: it takes a long time to build momentum. Better to snatch a lower gear and watch the revs jump.

In the 3000-4000rpm band, the car throws off its low-rev lethargy. Beyond 4000, it’s a flyer. It never delivers the powerful brutality of the Testarossa; but nearing the red paint on the tachometer, you’re still left in no doubt that you’re piloting an unusually fast car. As with the Ferrari, the BMW engine makes a wonderful sound, and it revs sublimely to its 7200rpm cut-out. It is a smooth, powerful and refined engine, but it has nothing like the through-the-range lung power of the flat-12. At low revs, you feel as though you’re in a standard 520i: it’s that sluggish.

It’s a lot thirstier than a 520i, though. An average of 16.4mpg is adequate by fast car standards, poor by mid-size saloon levels. The Testarossa, predictably, is even thirstier: it averaged 14,4mpg.

The Ferrari rolls less, feels sharper, and loses its hold of the tarmac at a higher speed. But the BMW handles better than the Testarossa. For all their track-car breeding, mid-engined cars – particularly ones that site their engines high, atop the transmission -are often less predictable than well sorted front-engined/rear-drive cars. Especially on public roads, which have constantly varying camber, and bumps. Or at the Castle Combe circuit in Wiltshire, which is about as smooth as a glass table hit by a shotgun blast.

The Testarossa, which is doubtless a pleasing companion on the billiard-table smooth confines of Ferrari’s Fiorano test circuit, was a real handful at Castle Combe. It went like a track racer down the straights, and accelerated so fast that it turned sweeps into serious bends. But the brakes – the pads of which probably had never been properly bedded in – started vibrating badly after a mere handful of laps, and the handling was unpleasant.

Pushed moderately hard, the Testarossa is a steady understeerer. Body roll is well checked, and the front tyres shriek in protest as they try to resist the natural, inveterate nose scrub. But push a little harder and, quite suddenly, you can feel the vast powertrain mass behind your shoulders rolling, and the outside rear tyre starting to lose grip. With all that mass moving behind you, the Testarossa becomes extremely ungainly, and very difficult to correct. You are similarly aware of this rotation of mass when you back off suddenly in the middle of a corner.

This change of behaviour is more sudden than in the frequently criticised 911, which builds up its tail-happy pendulous effect more progressively. Only an exceptionally talented driver could tempt the Testarossa into an oversteer slide, and hold it in that position: the steering – surprisingly low-geared – just isn’t sharp enough, nor informative enough.

In normal on-road driving, you’re unlikely to tempt the Testarossa into a roll-induced oversteer slide. The roadholding – helped by those large 255/50ZR16 rear tyres – is too secure, the cornering powers too reassuring. But chance your luck – or venture onto a private test circuit – and the ultimate lack of chassis balance will come as a rude shock. The old GTB -itself never a top-drawer handler – was a sweeter car to drive hard than the Testarossa; the new 348 – having less roll, and a much lower powertrain – is far superior. So, for that matter, is the Countach.

The BMW turns into corners with a little less verve than the Ferrari, and sways noticeably in conditions where the Italian car would remain flat. Yet it is a more controllable car. At lower speeds it interacts less with its driver but, when tanking on through corners, it can be held in glorious oversteer slides, its chassis communicating richly, the car easily controlled both by the throttle and by the steering. Its roadholding limits are slightly lower than in the Ferrari – the tyres start to lose their grip a little sooner – but, once over the threshold, the M5 still talks to you, still entertains you.

To boot, the M5 lacks the sudden and deceptive transition from understeer to oversteer. It understeers a little initially, before flowing into invigorating four-wheel drifts. Again, you are not likely to get the chance to enjoy such behaviour on public roads. But it’s nice to know what the car is capable of delivering.

Mind you, the extra weight of the new M5, over the likes of the M3 and Z1, means that this is not the sweetest-handling BMW in the range. It is sloppier and less responsive than those smaller and more manoeuvrable cars and, if anything, slightly less fluent than the old (and lighter) M5, one of the best-handling saloons we have ever driven.

On the public road, the Ferrari – more firmly damped and sprung – tracks more surely, and changes direction more nimbly, despite the low-geared steering. It feels massively secure, clamping itself to the tarmac. But for brisk public road driving, the BMW still wins. The Ferrari’s massive width is its Achilles heel: it is too bulky to be threaded down a narrow A or B-road with any confidence. It is too wide to be driven unconcernedly in a city as well: London width restrictors (you'(l have three inches of clearance either side) have to be treated with great circumspection.

If you want to take a friend away for the weekend, the M5 plainly gives you more room for luggage and odds and ends (not to mention a couple of extra friends). But, by mid-engined two-seater standards, the Ferrari is not bad.

Headroom and legroom are generous enough for tall people, and two big chaps can sit in the car without rubbing shoulders. Mind you, cabin width is deceptively mean, given the car’s massive girth. A person of slightly taller than average height, will be able – just – to touch the passenger side door trim from the driver’s seat.

The BMW has more head and shoulder-room, and just as much legroom. Yet, by saloon standards, it is not an especially commodious car: it is a strict four-seater (the space in the middle of the rear bench is occupied by a sliding drawer storage box, offering good – if unusual – stowage capacity). The boot is wide and long, but deceptively shallow. It’s much bigger than the Ferrari’s, though, which is just big enough for a small suitcase. A large carpeted shelf behind the seats helps.

By hairy-chested supercar standards, the Testarossa is a surprisingly comfortable car. The ride, although undeniably firm, is extraordinarily supple for so low a car, and one wearing such vast rubber. The seats, beautifully trimmed in leather, are comfortable, and multi-adjustable (by fiddly little manual switches). Fact is, the whole cabin looks pleasing, and hand-crafted. It is swathed in leather and rich red carpet (although the latter is not particularly well fitted). Only the Fiat corporate switchgear and instruments (unattractive orange-on-black affairs) cheapen it.

The cabin is a class above the M5’s, all the same. The BMW’s interior looks just like a 535i’s (apart from the cloth upholstery, featuring little tricolour BMW Motor-sport motifs, which look naff). And that means it’s well sculpted, but plasticky, and very mass-produced. The instrumentation is the same as a 535i’s, apart from replacing the economy gauge with and oil-temperature instrument (why not oil pressure?). As with the Ferrari, the BMW chairs are multi-adjustable (although electrically, rather than manually), and support the body well. And the M5’s noticeably softer springs and dampers ensure an even better ride than that offered by the Testarossa: it’s a little thumpy on broken London blacktop, but far more supple than the fine handling would suggest.

Drive long distance, and the BMW is a far more soothing companion. The Ferrari’s wide rubber, and tighter suspension bushings, mean that a lot of road roar is faithfully communicated into the cabin. Wind noise suppression is also poor, and the engine is far less muted than the BMW’s. In short, the Ferrari’s cockpit is a much noisier place to while away the time.

The BMW has easily the better heating and ventilation: on a cold, rainy day, the Ferrari’s screen demister had a hard job giving us clear vision.

Here’s the crunch. The BMW may be easier and more soothing to drive, and it may be able to thread its way down a winding public road with more confidence and speed. But, like all 5-series models, it is not a friendly car. It is massively competent, but not really fun to drive.

That’s where the Ferrari is different. Its steering is lower-geared and suffers from so much kickback that, on bad roads, it can deliver your hands a real jolt. But it talks to you, this car. It has a personality, it’s animate, unlike the BMW.

It isn’t just the lively steering – quite clearly, on close terms with the front wheels – that fosters such intimacy with the driver. The gearlever, a dainty chrome stick in a six-fingered gate, snicks from cog to cog. You can feel those gears meshing. In the BMW, the change is lighter and shorter and quicker, but it’s also a good deal more vague, and rubbery.

The accelerator pedal of the Ferrari is also vastly more responsive than it is on the German car. It isn’t just the fact that the Testarossa’s engine has more grunt. Rather, you are always aware that minute variations in throttle openings mean speed differences. In the M5, there is far more slack. Things don’t always happen, when you use the M5’s right pedal. Furthermore, the clutch of the Ferrari has more mechanical delicacy than the BMW’s (although it also requires more strength, as do all the Testarossa’s major controls).

In more practical day-to-day functions, the BMW is well ahead. It has better quality switchgear (both in terms of appearance, and tactile qualities), better ergonomics (an art in which BMW is master), and better all-round visibility (although the Testarossa is excellent by mid-engined standards). The M5 also has a better driving position: you sit straight ahead, whereas in the Ferrari (as in all mid-engined cars) your legs are canted to the centre line, to clear the intrusion of the front wheel-arch.

Both cars have adjustable steering wheels: the BMW’s for reach, the Ferrari’s for rake. And both wheels look handsome with their leather rims, and inviting.

The BMW is more practical, more comfortable, handles better, and is faster on the majority of public roads. It is also vastly less intimidating, friendly though the Testarossa may be by Ferrari standards. There’s no getting-to-know-you process with the M5. If you can drive a Sierra briskly, you can drive an M5 very fast. In contrast, most motorists would drive a Sierra faster than a Testarossa.

Yet the M5 is not as good as we’d hoped. It’s fast, all right. And it’s quite roomy, and blissfully practical (use it every day, come what may, and it won’t complain, and neither will you). It’s well balanced (unlike the Testarossa). But, as with the 535i on which it’s based, this car does not involve you enough, It’s too sterile to be thrilling, not animate enough truly to be desirable. And the low-rev lethargy, on a car with such pleasing ultimate performance, is a rude shock. That intimate man-and-machine union that is at the core of Ferrari motoring, is missing. It doesn’t have the drama of a powerful mid-engined supercar. People who sell their Ferraris and their Golf GTis, hoping their qualities will be merged in the M5, will be disappointed.

There’s no reason why a four-door saloon cannot offer real supercar pleasures. More sharpness, and the M5 would have won this comparison un-reservedly, instead of merely gaining victory with the huge proviso that, if it is driving pleasure you seek, then it must be the Testarossa.

Statistics

BMW M5

Engine: 3535cc, in-line six, 315bhp @ 6900rpm, 265lb ft @ 4750rpm

Transmission: five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Performance: 6.6sec 0-60mph, 155mph (limited), 16.4mpg

Weight/material: 1668kg/steel

Dimensions (length/width in mm): 4711/1750

Ferrari Testarossa

Engine: 4942cc, flat-12, 390bhp @ 6300rpm, 361lb ft @ 4500rpm

Transmission: five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Performance: 5.8sec 0-60mph, 180mph, 14.4mpg

Weight/material: 1506kg/steel

Dimensions (length/width in mm): 4486/1976

Read more iconic car features