The roads are gloriously empty, seductively so. A marrow-numbing November coldness, combined with the depressing shortness of winter days, has cleared Exmoor of all but the hardiest tourists. Even the sheep have abandoned car-baiting for the season, content merely to graze, gaze and bleat.

People often say its impossible to enjoy the full potential of high-performance cars anymore. That there’s nowhere you can drive fast, safely. Most of the time they’re right. The impediments to fun-seekers are enormous, and growing worse. But it is possible, if you’re lucky. And up here, on the tumbling, sinewy roads of a blissfully deserted Exmoor, we’re set for two days of unbelievably good fortune.

Not only are the road conditions in our favour, we’ve arrived in a four-pack of covetable coupes. Covetable because they look tremendous. Because they go hard. Because they’re sensibly sized. Because while they aren’t instantly affordable to many of us, they represent a vaguely achievable aspiration. Porsches, Ferraris, Jaguars and the like belong in never-never land, and probably always will; with a bit of imagination, and the sale of a grandparent or two, even the most costly of our Exmoor collection, the £21,975 BMW 325i Coupe, might just find its way onto some of our driveways.

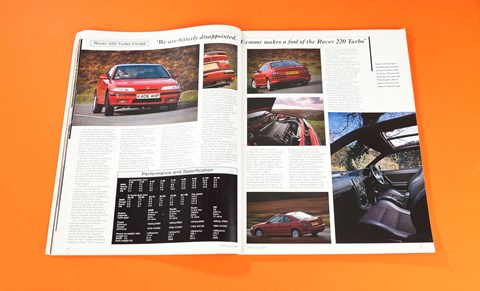

The fastest of the foursome, the spanking new Rover 220 Turbo (at £18,315, it’s also the cheapest) has the on-paper potential for a head-to-head ruck with the super-coops from Stuttgart and Maranello. The claimed performance figures of 150mph and 0-60mph in 6.2sec are the stuff supercars were made of not so many years ago. And they make the 220 Turbo the fastest road-Rover yet built. The other two cars we’ve brought to exercise on the moors – the VW Corrado VR6 (E20,495) and the brand-new Honda Prelude VTEC (no firm price yet, but likely to be between £20,000 and £20,500) – aren’t so far behind the Rover in test-track statistics, but are, as we’ll get to later, a way in front in the areas that really count.

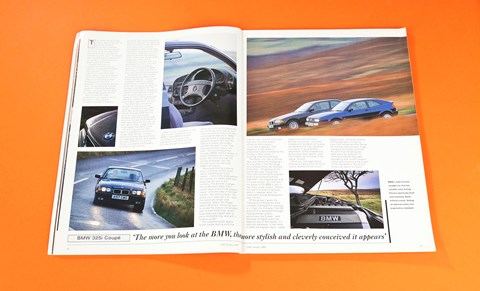

An enticing quartet, then, each in possession of the main coupe requirement – a sleek, distinctive body. But while each is undeniably stylish, their styles are very different. All but the Honda are based on floorpans of saloons and hatches. Most similar to its donor is the 325i Coupe, tested here with BMW’s new VANOS variable camshaft timing gear, now standard for both the 2.5 and 2.0-litre straight-six engines. Some will criticise the Bavarians for not being more radical, but there are sound reasons for the conservative approach. BMW has identified a large body of potential buyers who love the idea of a coupe, but simply wouldn’t be seen in one. Folk who want to look suave, not flash. You could argue that driving a BMW, even a saloon, is pretty ostentatious in the first place. But when you see the Coupe alongside, say, the Prelude, you can see what BMW’s driving at.

Penny-punching certainly wasn’t a motive for the close family resemblance to the saloon – none of the body panels are shared, no matter what your eyes may tell you to the contrary. The bonnet is longer, the windscreen starts 3.0in further back and is more steeply raked – ditto the rake of the rear screen – the roof is shorter, the whole car’s lower by 1.0in, and the doors are longer and frameless. Sadly, the Coupe retains B-pillars; removing them, to create the classic convertible-with-a-steel-hood look, would have required a great deal of extra strengthening, and with it, surplus weight.

The long-bonneted, grand tourer coupe styling suits the 3-series well, and the more you look at it, the more subtly attractive and cleverly conceived it appears. The elegance of the saloon’s proportions aren’t harmed by the change in their ratios; if anything, they’re enhanced.

The Rover, too, has a familiar face, but there’s no mistaking it for any other in the 200 range. Very different from the ordinary three-door – 75 percent of the panels are new, though the outer skins of the doors and the boot lid are shared with the Cabriolet – the coupe body is an in-house design. Its fines lack the grace of the BMW’s, but it has more visual impact. There’s the look of a crouching feline about it; appropriately, its codename during development was Tomcat.

Of the group it gives the impression of being the most compact, although the smallest is, in fact, the Corrado. The 220 pulls off this deception through having slender pillars – particularly the C-post – and because its flanks aren’t as deep as any of the others’. It’s also the narrowest. It has most to offer the boy/girl racer – deep, aggressive front and rear bumper mouldings, intricately shaped and scooped out to give the appearance they somehow contribute to ground-effect downforce, boldly shaped sills, body-colour boot spoiler, and the funkiest set of alloys in the group. Crucial.

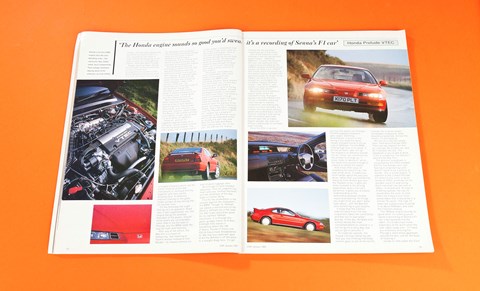

Mind you, the eagle-faced Prelude is hardly short of visual drama, Boldest of the bunch, big-wheeled, and deep-flanked, the Prelude takes its styling cues from neither another Honda nor another manufacturer. Huge triangular tail-lamps reinforce the point that the designers were out to be different. To commemorate the Prelude’s availability with a VTEC engine, a big, boot-mounted wing is part of the standard kit. But as the wing is an option for lesser models, and the alloy wheels are the same as those on the 2.3, your neighbours will have to stare hard at the badging on the back to spot you’ve bought the hottest, most desirable Prelude.

Badge-spotting helps identify this Corrado as the one with the correct number and arrangement of cylinders. Five-spoke Speedline alloys are a bit of a clue, but they’re all you get, for otherwise, all’s as before. The Corrado’s the oldest design here, but still quite a looker, despite its out-of-vogue chunkiness. It’s as unusual and distinctive as the Honda, and conceals its humble Golf origins.

During an early-morning motorway cruise to Exmoor, the two-door foursome have the chance to reveal only a part of their natures; an important part, nevertheless. Honda and VW assail the ears with a bawling match between rubber and tarmac; of the pair, the Japanese car is the bad dude of the decibels, though the Corrado is only half a holler away. If there’s excessive wind or engine noise, neither gives you the chance to find out.

Both have suspension that, when traversing motorway joining strips or poor repairs, seems over-firm; they’re even more harsh, and noisy too, on fractured, fissured, urban roads. The Rover’s ride quality isn’t that much better in town, but at least it’s quiet about its agitation. However, what all its higgledy-jiggling shows up is that body rigidity suffers a touch from being targa-topped. The 220’s glass roof is comprised of a couple of panels which can be either tilted up at the rear individually or removed entirely, together with their centre dividing strut. A reflective coating on the glass holds sunrays at bay during top-on summer runs.

On the motorway the slight flexing isn’t so apparent. Road roar is well suppressed, too, the engine being the greatest disturber of the peace. Overall noise levels are considerably lower than in the Corrado or Prelude, but the BMW leads the way for hush and harmony. After any of the others, the Bee-Em is a haven of tranquillity: like listening to Tasmin Archer instead of Iron Maiden. Its chassis (almost six inches longer in wheelbase than its closest rivals here) soaks up the lumps and bumps, while a stiff shell and good sound-proofing sponge up the din from all other sources. Occasionally wind can be heard trying to nibble its way through the door seals, but it’s much improved over early 3-series saloons in this respect.

The airiest, most spacious, most comfortable cabin (and seats) of the quartet also endears the BMW to the motorway traveller. Back-seaters will like it best, too: it’s the only one that won’t give them a cricked neck. In spite of having the shortest wheelbase, the well packaged Corrado is next best for back-seat riders. The Rover’s mean on headroom (though there’s plenty of space for legs) while the Honda, which from outside looks the big boy of the group, will keep only Lilliputians happy. And Lilliputians’ luggage is all the Prelude’s boot is good for. Largest, by a couple of suitcases, is the Bimmer’s boot, which can be extended further by folding the split rear seat. Both the Corrado and Rover have folding seats, too; of the pair, the VW has the largest, best shaped luggage area.

But enough of level-headed appraisal. Time for judgment by heart and soul. Exmoor beckons and the shortness of the day begs no further delay. First for the shakedown is the slowest against the stopwatch – the BMW. Though its 144mph top speed is second only to the Rover’s 147mph (on a flat road the 220 Turbo should be good for its claimed 150mph maximum), in a through-the-gears grudge match its 8.9sec 0-60mph time leaves it wondering where the VW (7.8sec), Honda (7.0sec) and 220 (6.5sec) have disappeared to. Not that you need test gear to tell the Bimmer’s off the pace in a straight drag race. It’s got nothing like the low-down, crackerjack go of the others.

Part of the problem is that although it has the second best power output – 192bhp at 5900rpm – it’s also the heaviest. Not even the newfound mid-range muscle provided by the VANOS variable camshaft timing system can help it out. VANOS (the initials stand for something that doesn’t easily translate from German) leaves the power of the 2494cc 24-valve twin-cam straight-six unchanged, but increases slightly maximum torque – now 181lb ft – and allows it to peak at 3500rpm, 1200 lower than before.

Microchips and a hydraulic switch valve control the camshaft timing. At engine speeds less than 3000rpm the timing is retarded, reducing valve overlap to improve combustion, and making the engine run more smoothly. For cleaner running (some exhaust gases are sucked back into the mixture, cooling it and cutting NOx emissions) and more efficient gas flow at higher engine speeds, the inlet cam timing is advanced, to increase valve overlap.

Once the 325i is up and running, the sports car emerges. Throttle response sharpens, gets urgent. Storming performance is yours for the taking if you keep the tacho needle screwed round to the far side of 5000rpm. For the BMW, holding high revs is no sweat. It thrives on them, laps ’em up. The engine’s so dreamily smooth the rev limiter can sometimes be the prompt to change up, It never loses its decorum, yet at the same time sounds enough of a beast to satisfy the zealot.

And it has other ways of rewarding the discerning. Like rear-wheel drive. It makes you think harder about the way you drive, rather than just blundering along as front-drivers give you the freedom to do, It gets you more involved in the driving experience, and in the car’s dynamics; it gives you a clearer understanding of the relationship between throttle inputs and steering. All things you might think you don’t really care about – until the Bee-Em stirs something in your psyche.

It helps that the 3-series’ sophisticated multi-link rear suspension takes the uncertainty and fear out of rear-wheel driving. In the dry, the back end wilfully resists the most concerted efforts to unstick it; it will let go on a rainy day, but you’ve got to provoke it.

At moderate speeds, the Coupe’s billowy damping can fool you into thinking that body control goes to pot at ten-tenths. Instead, the 3-series shows remarkable composure, feels beautifully balanced. Across the moors, it’s exhilarating.

No less so is the four-wheel-steer, front-drive Prelude VTEC. There are two reasons for this: a) it sounds like a track car, and b) it handles like one. The drawback is you’ve got to drive it like a competition car before it delivers the Big Thrill.

The glorious soundtrack is composed by the VTEC-headed 2157cc four-banger twin-cam. Saving on engineering costs doesn’t seem to be a priority at Honda – this is a new engine, in addition to the current Prelude 2.0 and 2.3-litre units. A quick recap on VTEC, a Honda-ism for variable valve lift and timing. Each camshaft has two sets of lobes – mild and wild. At slow to middling speeds, the low-lift squad does the work, to help make the torque curve more presentable than it would be in a normal 16-valver. The high-lift lobes are hydraulically muscled in at about 5000rpm, and start the fireworks display.

The 183bhp engine sounds so good when it’s cooking you’d swear a recording of Senna’s F1 car is being piped into the cabin. It’s a rapturous noise, especially at the point when the cam lobes swap over – it’ll have you endlessly shoving the Prelude’s short-throw gearlever around the box, just for the buzz of hearing it.

Unlike its little sister the Civic VTEC, the Prelude has a lot to offer low down as well as on high. It has enough fourth-gear punch to spar with any rival here. And enough flat-chat go to outpoint all but the Rover. Like the BMW, it feasts on high revs, converting them into lightning-fast throttle response.

Quick response is an attribute of the all-wishbone chassis, too. It’s bestowed by the four-wheel steering, an electronic system, which takes into account vehicle speed and the rate at which the steering wheel’s being twirled, in addition to steering angle. Up to 18mph, the rear wheels steer in the opposite direction to the fronts, enabling the car to turn more tightly. At high speeds fronts and rears turn the same way, increasing stability. And at medium speeds it depends on the steering input, although the system reduces the counter-steer effect as road speed rises.

It takes a bit of getting used to, although the benefit in town is immediately obvious. There’s a slight feeling of detachment through the narrow-rimmed, leather-bound wheel, at its worst at low speeds, and still evident at higher velocities. In all but the tightest corners, the Prelude exhibits a stability and neutrality that inspires great confidence. It is possible to bamboozle the control box – pile into a corner too fast, a lot of lock on, scrubbing off speed as you go, and suddenly the system can elect to steer the rear wheels in the opposite direction to the fronts. Unsettling for both car, and driver. It doesn’t happen often, but it’s worth remembering that it can.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that in extreme situations the Corrado, too, can give a little waggle at the back. Tight corner, too fast, turn too soar) for the apex. In two days of hard driving over the moors this happened only the once, but it was a lesson learned. Nevertheless, it doesn’t detract from the fact that the Corrado is one of the world’s most dependable handlers, a great forgiver of mishandling.

But it isn’t a dullard. Quite the opposite. Stick your index fingers into both corners of your mouth. Now pull up. That’s how the Corrado makes you feel. As in the Honda, its hard-edged low-speed ride doesn’t translate into flat-out jitters. The faster you go, the greater the feeling of control and reassurance. It doesn’t turn in as briskly as the Prelude, but its steering communicates better, puts you closer to the action. Neither lets you forget through which end the power is channelled, though.

Talking of power, what a difference it makes to your perceptions of speed and progress, having six, rather than four, normally aspirated cylinders, Going fast seems so undemanding in the Volkswagen compared with the Honda, though the two are very evenly matched at the test track. The Corrado’s transversely mounted, 190bhp single-cam 2.9-litre V6 burbles with accessible brawn, and seldom gives the impression of having to try too hard. Mid-range lustiness is just a toe-twitch away. Keep stretching the right hoof and you release a fresh burst of brio. There’s no hysteria, no frenzy, just snarl and thrust.

Thrust is something the Rover’s not short of – any gear, any time. That is its strength, and its downfall. Because, sadly, under its chic, feline skin, this Tomcat’s a dog. A howler. Forget the, ‘An, but it’s so much cheaper than the others,’ argument. Its deficiencies are more fundamental than that, and price is no excuse for its flaws.

We’re bitterly disappointed. We’ve come to Exmoor expecting great things of it -hell, all that performance in a car the perfect size to be enjoyed on some of Britain’s best driving roads. But Exmoor makes a fool of the 220 Turbo. Still, the news isn’t all bad. Rover’s 16V 2.0-litre twin-cam T-series engine is a masterpiece of the turbocharger’s art. It’s the same engine that powers the 800 Vitesse, tuned to give another 20bhp. As for the intercooled Garrett T25 turbo, apart from the occasional muted whistle, as soft as a canary’s sigh, you’d never know it was there. You certainly can’t feel it cutting in or out.

But you are aware that it has an amazing effect. The Rover unit develops a hulking 175lb ft of torque right down at 2100rpm, as if it were an engine with twice the number of cylinders. And that high point on the torque curve isn’t a freak blip, its the crest of a gentle swell. The gearbox is merely a distraction in town driving. Top gear at 1000rpm? Certainly, sir.

On the motorway or ambling along B-roads there’s zap aplenty for overtaking or relieving boredom, and that’s without trying. By using only a fraction of the available revs, just a couple of inches of the available throttle travel, you could easily convince yourself the 220 Turbo is a very fine thing indeed.

And look at our performance figures. It scorches the opposition in all the standard performance measurements. Hitting 60mph from standstill in 6.5sec is hot stuff in any company; here it’s sensational. Given a flat road rather than Millbrook Proving Ground’s banked track, the 147.6mph it recorded in our hands should easily translate into the claimed 150mph. Impressive stuff.

Or is it? Before we undertook that top speed run, Rover advised a number of precautions. That we swap the 195/55 ZR15 Michelins on the car for another set, shaved down to a tread depth of 3mm. That the ‘new’ rubber should be inflated to 51psi. Then, to warm up the tyres properly, we must run four laps at less than the maximum, Safety is foremost in our minds for any trip to Millbrook, but never before has a manufacturer laid down such rigid guidelines. How many autobahners, we wonder, will be as conscientious?

Perhaps we shouldn’t worry. On the evidence of our Exmoor exploits, the Rover’s misbehaviour at lower speeds will discourage anyone from going for broke. In the face of the engine’s mighty outputs, the front wheels don’t stand an earthly. The problem is addressed, but not answered, with a Torsen torque-sensing traction-control system. Designed to ferry the torque across to the wheel with most traction, in the 220 Turbo it proves useful only when pulling sharpish out of T-junctions or powering out of roundabouts. It simply doesn’t work as a controller of traction, merely a moderator of wheelspin in limited circumstances.

For the most part, the front wheels have a life of their own. Power corrupts them, tempting them often to abandon their role as steering gear. Guessing which way the torque-steer will fling the car next is like playing roulette – a game of chance and luck. Under power the whole car writhes and squirms as if an exorcist were trying to rid its body of a plague of demons. Throw in a decent camber and the fight to retain control becomes an epic battle.

Powering hard through corners is not recommended. Unless you enjoy that much understeer, And how quickly can you wind all that lock back off again? It had better be quick, otherwise your rapid exit from that tricky corner could be mighty haphazard.

Matters are worsened by the stiff suspension set-up. Battered black-top can pummel the Rover off-line, and once the chassis is unsettled, the traction soon follows suit. Lack of wheel travel means even quite modest crests can put air between rubber and road. None of the others is similarly troubled.

The 220 Turbo is totally without finesse, unless you care to drive using only a fraction of its potential. Then what is the point? This is Rover’s Vauxhall Astra GSi – great engine, great looks, beautifully styled, well appointed interior (Rover always does its cabins so well), incompetent chassis.

It doesn’t just finish fourth in this comparison, it finishes rock-bottom last. It’s the company’s calamity coupe. And we were hoping it would be so good. If you admire its looks, and we do, plump for one of the more modestly powered versions.

Putting the other cars in order is far harder. All are excellent, all appealing, all entertaining and fast. Each one a good buy, each slightly different in character. Not without regrets, the Prelude finishes third. Glorious engine, rattling good chassis, but until you push it right to the limit, it doesn’t strike up enough rapport with the driver. In spite of goodies like driver’s and passenger’s side airbags, air-conditioning and leather, its futuristically styled cabin leaves you cold. Short of space, too, for passengers and their luggage.

The Corrado VR6 remains a favourite, but doesn’t win. Compared with the BMW it’s too noisy and its ride is too taut, But it ain’t half fun. It’s a gutsy performer and handles superbly. If you really can’t come to terms with rear-wheel drive, the VR6 makes an admirable 3-series substitute, though it lacks its fellow German’s civility.

Once more a 3-series leads the pack, despite being disadvantaged in the areas of price and performance. It’s an enthralling, captivating drive; one from which you will learn a little bit more each time. If you owned it, the 325i Coupe would hold your attention for longer – for years, even – than any of the others. That it’s also the most refined and spacious, means your head can follow your heart.