► A Lotus icon versus the brand’s future

► One of the greatest against a future great

► Is there any of the magic in the newcomer?

This feels like being in a moving painting. Arms stretched out ahead, hands grasping a tiny steering wheel alive with vibration and information. Capri-blue sky with speed-line clouds overhead. Red-white kerbs flickering under fat slicks. The throttle pedal is heavy, long, a kind of mechanical test of willpower. Override friction and instinct and push it to the stop: those speed lines intensify to a strobing blur; hands seem to move away as the acceleration heaves my body backwards, a dead weight harnessed into an aluminium missile. How can a 50-year-old car be this fast?

The Cosworth DFV just behind my shoulder blades is singing, singing, singing up a never-ending scale, revs soaring for the sky – and we’re still only two thirds of the way to its redline. Tilt head to check the tiny, round mirrors. Evija. Evija? Yep: because the only thing more surreal than the chance to cut loose in the greatest F1 car ever made, in JPS black and gold, is the chance to do it in company with the new Lotus hypercar that’d kill for a legacy as glorious as Lotus 72, chassis number 5.

The two black cars on these pages are separated by 50 years and very different missions: the Evija hypercar is here to spearhead Lotus’s electric future; the Type 72 F1 car spearheaded Team Lotus to Grand Prix glory time and again through the first half of the ’70s. We’ve brought them together because the 72 typifies everything that has made the greatest Lotus cars – road and race – special: innovative design, pretty lines, abundant performance through absent mass, and a place in the history books. As New Lotus trades engines for e-motors, is there any of the 72’s magic in the Evija? That, and the opportunity to drive one of the world’s fastest ever production cars and its greatest ever F1 car is not your average Monday.

Chapman’s Cayman: full story on the Lotus Emira

Greatest F1 car ever? You could make a case for McLaren’s MP4/4, which won 15 out of 16 races in 1988. Or last season’s all-conquering Mercedes W11. But the Lotus 72 (or the John Player Special, as it was often called at the time, in deference to its headline sponsor) raced for six seasons from 1970 to ’75, and won Grands Prix in five of them, a winning streak unthinkable before or since. Along the way it claimed five world titles (two drivers’, three constructors’). Today, like a smartphone, an F1 car is obsolete in a matter of months, but the 72 was so innovative it effectively took a two-footed jump into the future – and stayed there while the rest of the grid caught up. Can the Evija do the same for electric supercars?

As it whirs to a halt in the Lotus test circuit’s pitlane and lead dynamics engineer James Hazelhurst swings the driver’s door upwards to step out, you half expect post-time-travel lightning to crackle all around. As the Type 72 must have done in 1970, the Evija looks like it’s driven straight out of the next decade. This is not the production Evija, but one of several hard-working prototypes testing its dynamic limits. The finished car, delayed by the pandemic, is planned to be with customers at the end of this year. Hence the matt black livery and complete absence of interior trim.

Duck under the door (which takes a chunk of sill away with it, like a McLaren, for ease of entry) and it’s all business: racing seats, rollcage and a smorgasbord of electronic testing gear. The first thing that strikes you is how low the seat is. It’s virtually on the floor. We’ve become used to battery-electric cars with big chunky sills and a fair bit of space between you and the road, to account for the batteries. Not here.

‘We wanted to get the driver really nice and low,’ Hazelhurst says. ‘We’ve positioned the battery where the engine would ordinarily be in a mid-engined car.’ That also puts you, the driver, in a cab-forward position, feeling almost on top of the front wheels. The nose is so low as to be out of view, while the wheelarch humps sit nicely in your peripheral vision. The ‘Becker points’ Hazelhurst calls them, after storied Lotus test driver Roger Becker, who felt a driver should be able to see exactly where the front wheels are, to place the car precisely.

‘Almost every aspect of this car prioritises handling balance – that’s something we know about,’ Hazelhurst says. Bewitching handling is a Lotus hallmark, of course, but an all-electric hypercar – that’s something entirely new for traditional Lotus fans to get their heads around.

A quick recap of the Evija’s basics: the first new Lotus under Geely ownership and originally revealed to the world in 2019, it’s a hypercar flagship, to get the car world talking about Lotus and warm it up for future electric sports cars. Four 17,000rpm e-motors (one per wheel) target a total output in excess of 2000 metric horsepower; 130 cars will be built, at £2.04m a go (£1.7m plus local taxes). Final 0-62mph time will be somewhere under three seconds; top speed ‘far north’ of 200mph. It’s seen 230mph in testing. Price aside, the really head-scrambling statistic is 0-186mph in under nine seconds. (The brutally quick McLaren 720S takes around 20 seconds.) This won’t just be the fastest Lotus ever; it’ll be one of the world’s fastest cars full stop.

Lotus’ electric plans: ‘forget hybrid, we’re going straight to electric’

Doesn’t sound very Lotus, does it? Shock-and-awe performance figures and Instagram-idol pricing all feel out of step with the delicate, do-a-lot-with-a-little Lotus sports cars we know and love.

Not the case, Hazelhurst promises: ‘The Evija has to have all the Lotus pillars: the steering feel, the way it breathes with the road, and to be capable on road and on track.’ And if its 168okg target weight is heavy for a Lotus, it’s still by far the lightest of all the EV supercars in development. (The excellent Rimac Nevera weighs 2150kg. And Porsche’s four-door Taycan – one of which Lotus has, for benchmarking – is more than two tonnes in its lightest form.) The first Lotus production road car with a carbon monocoque, the Evija’s bare chassis weighs 129kg and its compact battery pack weighs 600kg.

Thanks to the perfectly linear nature of the motors’ torque delivery, all couple of thousand horsepower will be managed with incredibly fine traction control and actively distributed not only between the front and rear axles but also across all four wheels, too. Except the development car I’m driving today isn’t running torque vectoring – or traction control. Nor is it wound up to the full 2000bhp-ish. But it is running a healthy 1600bhp or so, 77 per cent of which is permanently latched to the rear tyres.

And yet, a few corners in, you feel incredibly at ease in the Evija. There’s generous body movement here, including a fair bit of roll – no bad thing. It helps you judge what the car’s doing, and the car quickly settles into a stable pose. And, reassuringly, there’s a Lotus-ness to the way the Evija yields to the road without feeling wallowy. Its suspension (adaptive dampers, mounted in-board, with a third damper to control heave) easily absorbs the circuit’s low kerbs without them tremoring through the chassis. You quickly find yourself using all of them because this is a wide car – around 2m door-to-door. (Not a big one overall, however. Wheelbase is approximately the same as an Evora, and it’s not much longer overall.)

Okay, let’s up the pace. Should a car with 1600bhp, a 600kg battery at your back (weight distribution is around 37:63 front to rear) and no traction control not be borderline undriveable? Not the Evija. Get on the power and you find a nicely judged safety margin of very mild understeer. You can then either lean on it for reassurance or push through and tip into very controllable power oversteer.

Without the virtual e-diff function to modulate power to individual wheels, this prototype can spin its inside wheels merrily. Without the soundtrack of an engine’s revs rising or a revcounter needle to flare, it’s possible to not realise they’re still spinning until you’re some way down the straight (and each wheel can spin to 200mph). That won’t be the case in the torque-vectoring final car, however.

And there’s grip: lots of it. I try a standing start, half expecting the tyres to turn into bonfires: no wheelspin. There’s a smooth edge to the initial torque hit, without the shock of a clutch engagement, and the bespoke Pirelli P Zero Corsas are big (325 section at the rear) and soft enough to absorb huge force. I wonder if some customers might want more of an impactful, Tesla-style wallop, but Lotus hasn’t targeted dragster-style 0-62mph times. It’s above that speed where the Evija comes alive: 124mph to 186mph takes less than 3.0sec, and you can reach the car’s top speed in much less space than you’d expect, the team reckon. ‘It’s still trying to peel your face off all the way up to 190mph,’ says director of vehicle attributes Gavan Kershaw.

The Evija handles predictably off the power, too. Go deep into a tight corner, come off the accelerator and it behaves like a traditional mid-engined car, pivoting into lift-off oversteer. That it does so controllably speaks volumes for its stiff structure and the nous of its engineering team. ‘The position of the battery makes it a little like developing a car with a big, heavy V12,’ says Hazelhurst. ‘You’re working with the same challenges.’

This is not to say that the Evija feels as nimble as an Elise or Exige. You certainly feel the higher centre of gravity, due to the tall battery pack. It doesn’t change direction in quite the same way nor feel as lithe in its movements. But still: this is a car that feels inherently controllable despite its prodigious power, and it can hit 200mph in a heartbeat. Surreal.

But things are about to get yet more dream-like. A flash of black and gold in my mirrors and the serrated edge of a Cosworth DFV V8 cuts through my reverie as the 72 slices past. At the wheel is Classic Team Lotus director Clive Chapman (son of Lotus founder and leader Colin, who devised the 72 together with designer Maurice Philippe). He’s shaking the car down and bringing it up to temperature before I drive.

He’s driving it quickly, too. Crisp heel-and-toe downchanges into the hairpins, getting on the power so the car adopts a neutral balance mid-corner, and sparing few of the DFV’s horses once it’s warmed up.

‘The problem is, I always end up driving too fast,’ he says, mock-ruefully back in the pitlane. He debriefs lead mechanic Tim Gardner, and suggests moving the pedals back a little before I drive. ‘That said, I don’t mind if you don’t get full throttle…’ Chapman adds.

Of all the 72s, chassis 5 is a particularly special car. Raced almost exclusively by world champion Emerson Fittipaldi and nicknamed Old Faithful, it won Grands Prix in three different seasons. After a painstaking five-year restoration it was reunited with Fittipaldi, emotionally, to drive at Goodwood in 2019.

It’s a complex machine. ‘The restoration took an awful lot of work,’ Chapman says. ‘When racing in period, the Lotus mechanics were always the first to arrive and the last to leave. Changing a torsion bar means removing the fuel tanks; last-minute set-up requests caused some eye-rolling…’

Sliding down into the cockpit, it’s like lying in a very narrow bathtub with a small but supportive cushion in the small of your back. There’s a real patina here; original paint, the residue of the glue bonding the aluminium chassis panels. It even smells great – a blend of oil, fuel and hot metal. If you could bottle it, I’d buy it.

The steering wheel is further away than you expect, and a tad higher – your arms are almost straight, reaching ahead of you for the rim. The gearlever is to the right, with a bulge fashioned into the monocoque allowing enough space to get your hand around it. Into first gear (back and to the left; it’s a dogleg shift), enough revs to avoid stalling and… we’re away.

Into the first sweeping corners of Lotus’s test circuit, the steering response is instant – turn the tiny steering wheel by what feels like little more than a millimetre and the front slicks arrow for the apex. Over the plastic cockpit shroud you can just see the tops of the tyres, helping you place the car perfectly – the 72’s ‘Becker points’, if you will.

Out of the first hairpin I squeeze the throttle, its long travel a natural traction control – but traction from the huge rear slicks on this sun-warmed circuit is immense. Oh my word, the 72 is fast. Even after the Evija the old-timer’s speed is startling. This rebuilt DFV is running about 450bhp, says Gardner. In a car weighing 530kg or so, it feels sensational. Naively, perhaps, I’d expected the 72 to feel broadly comparable, in a straight line at least, to a modern supercar. It was designed 50 years ago, after all. But my sums put the power-to-weight ratio at 850bhp per tonne (a McLaren Senna is 659bhp per tonne) and it feels every bit as quick as that sounds. The thought of going wheel-to-wheel in a slipstreaming battle at Monza, or piling into the Karussell at the Nürburgring… Terrifying.

It’s remarkably smooth-riding for a racing car, absorbing the circuit’s kerbs sweetly. And that’s one of the most uncanny things about the 72 – it feels almost like an Elise in the way it blends immediate steering response with supple, malleable and yet controlled suspension movements. It was conceived to ruthlessly win races, yet it somehow feels inherently like a Lotus sports car to drive, too. Based on this first impression, in far-from-final prototype guise, the same is true of the Evija. It won’t be the first electric supercar, but there’s little doubt it will be the most involving, the most interactive – the most Lotus – to drive.

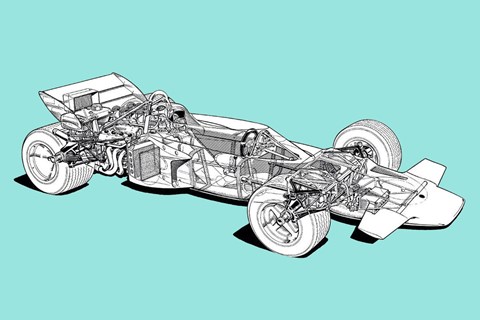

Three innovations that made the 72 a world-beater

Aero-first design…

Before this car, wings were bolted onto F1 cars after the chassis had been created. The 72 was the first to incorporate aero into its design from the start, leading to that iconic low-drag, winged-wedge profile.

…but grip-led handling

The 72 was an aerodynamic car, but downforce was in its infancy. ‘With the later ground-effect cars, it was all about aero; this car was all about maximising mechanical grip,’ says Classic Team Lotus boss Clive Chapman. To that end, its springless torsion-bar suspension was designed to look after the tyres as carefully as possible, and its inboard brakes kept heat away from softer, faster tyres.

Thinking space

As well as slashing unsprung mass by moving the brakes inboard, the 72 boxed clever with its radiators. Instead of one big one at the front, it was one of the first F1 cars to divide it into two smaller rads in sidepods. Advantages: lower nose, smaller frontal area, less drag, less weight from cooling pipes – and a cooler driver, although their feet were still kept toasty by the front brakes.

Three innovations at the heart of the Evija

Aero-first design…

Like the 72, the Evija’s shape has been designed from the get-go with aerodynamics at its heart. The Evija is a ‘porous’ design, shaped by taking things away rather than adding on. Airflow through the nose pushes down on the front suspension, and venturi tunnels duct flow through the car to its wake to reduce drag.

…but grip-led handling

Although lead dynamics engineer James Hazelhurst says the Evija’s aerodynamics are crucial to its performance, he adds: ‘We want to start with getting the mechanical grip right. Electric power opens up a whole new box of tools [traction management, torque vectoring] but we don’t want to use them until the grip without them is just right.’

Thinking space

Where more mainstream EVs floor-mount batteries in a ‘skateboard’ chassis, and Rimac’s Nevera hypercar positions its battery in an H-shape, dividing its bulk and weight along the car, Lotus has chosen to position its battery behind the driver, concentrating mass in the middle for the most responsive possible handling balance.