► Are hydrogen fuel cell cars the future?

► Pipe dream or The Next Big Thing?

► We look at fuel-cells and H2 cars

As the electric revolution redraws the automotive map at faster and faster pace, you’d be forgiven for thinking that battery electric vehicles (BEVs) have won the argument – and other forms of alternative fuel such as hydrogen fuel-cell electric vehicles (HFCEVs or FCEVs) have already lost. In reality, it’s not quite such a binary discussion. Life is rarely black and white, and the future of fuelling cars isn’t decided just yet.

Be in no doubt: some car manufacturers still believe that hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles could secure a place in a new, more fragmented future of the automobile. But so too could synthetic biofuels keep petrol and diesel combustion alive, while hybrids, autogas and other powertrains remain important considerations, as engineers explore multiple technologies in the quest to balance decarbonisation with consumer need.

In this article we discuss the feasibility of hydrogen cars and look at some of the opportunities and obstacles to their mainstream adoption. It asks the question: are fuel-cell cars the future?

How viable are hydrogen cars?

Automotive hydrogen fuel-cells have been around for decades and have long been caught in a chicken-and-egg situation. Can they launch before a valid infrastructure is ready? Or should a network of hydrogen refuelling pumps roll out first, paving the way for widespread demand?

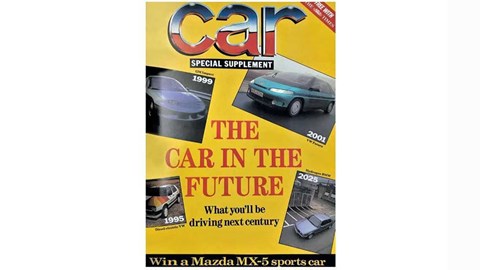

Long-time readers of CAR magazine will be familiar with the arguments around hydrogen in the automotive firmament. Our supplement The Car In The Future tackled the viability of H2 cars as long ago as summer 1990:

After sampling a hydrogen-powered BMW 7-Series prototype in Munich, our correspondent Roger Bell called it right: ‘Hydrogen power is not just round the corner.’ Over 30 years later, it’s still not clear if the revolution is imminent or far off.

Fuel-cell cars you can buy today

Fast-forward three decades and there are only two hydrogen-powered cars on sale today in the UK – a brace of fuel-cell models geared towards corporate users likely to have bunkered hydrogen at their disposal.

The Toyota Mirai retails from £49,995 while the Hyundai Nexo (below) costs £69,495. Such lofty prices might explain why they have not yet taken off, but many manufacturers persist with developing fuel-cell vehicles and believe that their myriad benefits are worth pursuing in a multi-fuel future.

Other carmakers still dabbling with the technology include BMW, Jaguar Land Rover, Mercedes-Benz and Renault – while Stellantis actually has a range of plug-in hybrid hydrogen vans on sale in Europe already.

There are even some performance concepts beginning to emerge, including the 2022 Alpine Alpenglow, a GR Yaris prototype with a hydrogen combustion engine, and an experimental BAC Mono.

What are hydrogen fuel cell cars?

Hydrogen fuel-cells are, fundamentally, electric cars – it’s just a question of how they store their energy onboard where they vary from pure EVs. Herein lie the advantages and disadvantages of the H2 brigade:

Benefits of hydrogen cars:

- Clean tailpipe emissions (only emissions are water)

- Ability to refuel as quickly as a petrol or diesel car

- Potentially longer range than current battery tech allows

- Avoids need for heavy and bulky batteries onboard

- Proven technology, mechanically simple

Disadvantages of hydrogen cars:

That last point is a fundamental one often overlooked in the fuel debate: how hydrogen is created dictates its cleanliness. Prepare to dust down your scientific rainbow as we consider ‘brown hydrogen’ (created through the gasification of coal or lignite), ‘grey hydrogen’ (produced by steam methane reformation using natural gas), ‘blue hydrogen’ (steam methane reformation, cleansed by carbon capture and storage) and ‘green hydrogen’ (made by electrolysis of water powered by renewable energy).

Discussion around automotive hydrogen becomes more compelling when green hydrogen is on the table. A new £240 million government Net Zero Hydrogen Fund (NZHF) is being established to promote the production of low-carbon hydrogen in Britain – it’s worth watching specialist firms such as ITM Power, Johnson Matthey and Ceres Power who are pioneering clean hydrogen here.

Will hydrogen fuel-cells ever take off?

Many western countries would need to pivot their energy supply dramatically to make hydrogen a viable mass transport fuel. The UK doesn’t have enough infrastructure today to make widespread adoption likely, but that could change given long-range investment and direction from government and industry.

The UK Hydrogen Strategy was published in summer 2021, setting out the government’s target to produce 5GW of clean hydrogen by 2030. A hydrogen economy that backed H2 for certain specific tasks – like fuelling the haulage sector, some buses, automobiles and even domestic boilers – is on the cards as Britain prepares to hit net zero by 2050.

The white paper spells out the future for hydrogen in the UK: ‘We expect that the role of hydrogen in transport will evolve over the course of the 2020s and beyond. To date, road transport has been a leading early market for hydrogen in the UK. Going forward, we expect hydrogen vehicles, particularly depot-based transport including buses, to constitute the bulk of 2020s hydrogen demand from the mobility sector. Fuel-cell hydrogen buses have a range similar to their diesel counterparts. Back-to-depot operating means hydrogen refuelling infrastructure can be more centralised and is likely to be compatible with distributed hydrogen production expected in this period.’

But what about hydrogen cars? Or is H2 only going to power commercial vehicles?

Politicians predict that hydrogen will be focused on heavy goods vehicles. ‘We will undertake a range of research and innovation activity which will focus on difficult to decarbonise transport modes, such as heavy road freight. As we demonstrate and understand these larger-scale applications we are likely to see more diversity in transport end uses in the late 2020s and early 2030s. By 2030, we envisage hydrogen to be in use across a range of transport modes, including HGVs, buses and rail, along with early stage uses in commercial shipping and aviation. Our analysis shows there could be up to 6TWh demand for low-carbon hydrogen from transport in 2030.’

Tellingly, even the government’s own white paper doesn’t foresee scaled take-up among private motor car users. But that won’t stop more globally enlightened car makers giving it their best shot.

You’ve just got to hope that the policy makers shaping the country’s infrastructure are on the same page as the industrialists planning the next generation of cars.