► How Schumacher changed F1

► Seven title victories, 91 wins

► Ex-champ marks his 50th birthday

Seven-time F1 champion Michael Schumacher is ‘in the very best of hands,’ according to his family as they mark the former race maestro’s 50th birthday on 3 January. He is being cared for at home in Switzerland after the catastrophic skiing accident five years ago that left him with brain damage.

‘You can be sure that he is in the very best of hands and that we are doing everything humanly possible to help him,’ his family said in a rare statement. ‘Please understand if we are following Michael’s wishes and keeping such a sensitive subject as health, as it has always been, in privacy.’

Read on for our profile on Schumacher, who became the most successful F1 racer of all time before retiring from the sport in 2012.

Michael Schumacher: the F1 legacy

It seems ridiculous now, but no-one was talking about Michael Schumacher on the eve of his Grand Prix debut in 1991. Bertrand Gachot was the only name on people’s lips; he’d been jailed following an altercation with a London cabbie and the British tabloids wanted answers. What had happened and who was to blame? ‘Gach uh-oh’ was one of the headlines doing the rounds.

The Belgian’s replacement at Jordan Grand Prix was boring by comparison. He was a shy and retiring 22-year-old from Kerpen, who’d never done anything as controversial as spray CS gas into the face of a taxi driver. He’d won the previous year’s German Formula 3 Championship and he was a member of the Mercedes junior sportscar team, but few people outside Germany knew how good he was. Even Mercedes believed Heinz-Harald Frentzen to be the fastest of its young chargers.

Attitudes towards Schumacher were about to change irrevocably, however, and Formula One would never be the same again. While Fleet Street continued to seek out quotes about Gachot ahead of the 1991 Belgian Grand Prix, Schumacher quietly took to the track in the Jordan 191. On his second flying lap of Spa-Francorchamps – a track he’d never previously seen – he took the fearsome Eau Rouge flat-out. To put that into perspective, his team-mate Andrea de Cesaris managed the feat only once during the entire weekend.

Legendary journalist Denis Jenkinson was watching from Eau Rouge and remarked to a colleague: ‘Who’s that guy? He looks special.’ That’s the same ‘Den Jenks’ who’d interviewed every F1 world champion since 1950.

Schumacher went on to qualify seventh for the race and despite cooking his clutch at the start and retiring on lap one, he’d done enough. F1 czar Bernie Ecclestone wanted him in a top team and facilitated an immediate switch to Benetton, for whom Michael finished fifth at the next race in Italy.

In the space of two weeks, Schumacher had gone from zero to hero. He was just two races into his 18-year F1 career, but he was already one of F1’s most bankable stars and he’d become an overnight sensation in his native Germany. It was manna from heaven for Ecclestone.

‘We [F1] needed him,’ says Bernie, who was so transfixed by Michael that he went to support him in a sportscar race at Magny Cours the week after his F1 debut. ‘He was fast, he was young and he was German – he ticked all the boxes.’

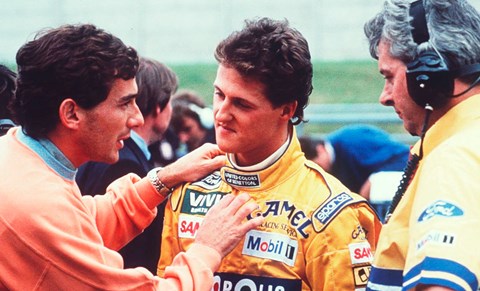

Such was Schumacher’s self-confidence that he was happy to ruffle a few feathers from the outset. After the 1992 Brazilian Grand Prix he accused Ayrton Senna of ‘playing around’ with him during the race, and he aggravated the legendary Brazilian further when he blocked him during a test session at Hockenheim later in the year. What seemed like a fairly trivial incident resulted in Senna grabbing Schumacher by the collar and reading him the Riot Act.

‘Michael wasn’t intimidated by anyone or anything,’ says Gary Anderson, Jordan’s then technical director. ‘He took the whole Spa weekend in his stride and he was happy to race wheel-to-wheel with the best. He was very impressive.’

For all his public bravado, Schumacher was clever enough to view his first couple of years with Benetton as his university years, during which he learnt how to maximise the potential of an F1 team. Team-mates Nelson Piquet, Martin Brundle and Riccardo Patrese came off second best, Brundle describing Michael as having the ‘guile of an assassin.’

Was he cunning, or was he merely astute? After all, it was Schumacher who realised before anyone else that there was a direct correlation between physical fitness and on-track performance. When Michael made his F1 debut, he had a resting heart rate of around 40bpm (average is 60-100bpm) and in terms of body mass index he was fitter than any other driver on the grid.

‘I want to be 200% physically prepared,’ he said. ‘Even at the end of the race I want to have something in reserve; I don’t want to feel tired at any point because that will affect my ability to drive the car on the limit.’

Other drivers were fit, but they weren’t as meticulous in their preparations. Schumacher raised the bar: he cycled, he ran, he swam, he lifted weights and he watched his diet. That’s not to say he lived like a monk because he did enjoy a celebratory drink – something that was encouraged by Benetton boss Flavio Briatore – but he didn’t party often and he was always the first in the gym the next morning, sweating out the excesses.

‘Michael’s fitness was a pain in the ass,’ says Gerhard Berger. ‘We were all pretty fit back then because we had to be. The cars were heavy; they had no power steering and they had manual gearboxes. You couldn’t do the job if you weren’t fit enough, but Michael proved that there was fit and fit; suddenly we had our teams asking why we weren’t as fit as him and we all had to train more as a result. You can imagine what I thought about that!’

Thanks to Schumacher, fitness became another gauge of a driver’s worth. Irrespective of driving talent, drivers would no longer be taken seriously if they weren’t super-fit and some great talents have since fallen foul of this new yardstick.

If fitness was the most tangible way in which Schumacher changed F1 forever, he left his mark on many other aspects of the sport. He understood that he needed to surround himself with the best people if he was to win races and, having found the magic ingredients at Benetton with tech bods Ross Brawn and Rory Byrne, he kept hold of them for the duration of his career. They moved with him to Ferrari in 1996, and it was Brawn who lured him out of retirement in 2010.

But Michael wasn’t just about keeping the star names happy; he was brilliant at looking after the entire race team. He knew everyone’s name, something that very few drivers master, and he was good at the minutiae. He remembered people’s birthdays, even their wives’ birthdays, and these small gestures created unflinching loyalty between Schumacher and the people around him.

‘Michael wasn’t only an incredibly impressive driver,’ says Ferrari technical boss James Allison, ‘he’s an incredibly impressive person. When I worked with him, he laid great emphasis on the team. I’m not saying he didn’t have an ego, but the team aspect of what we were doing was important to him and that’s unusual in a driver of his calibre.’

Until Schumacher introduced the idea of loyalty between a driver and his engineers, a technician’s loyalty had predominantly been to his team. Patrick Head was so devoted to Williams that he became a shareholder; McLaren’s modern-day success was built on the brilliance of design king John Barnard and Brabham became an extension of Gordon Murray’s innovative thinking.

Thanks to Schumacher, it was common practice for an engineer to follow a driver around the pitlane. Jock Clear followed Jacques Villeneuve from Williams to British American Racing in ’99; Adrian Newey followed David Coulthard from McLaren to Red Bull in ’06; Tony Ross followed Nico Rosberg from Williams to Mercedes in ’10; Andrea Stella went from Ferrari to McLaren with Fernando Alonso in ’15, and there will be more in the future.

What these newfound driver-engineer bonds demonstrated was a fundamental shift in the power of the drivers. When Schumacher switched from Benetton to Ferrari in ’96, not only was he the best driver in F1, he had the power to bring Brawn and Byrne with him. That was gold dust to the Scuderia, which hadn’t won the drivers’ title since 1979, and resulted in Schumacher commanding a record salary of £60 million per year.

With the big bucks came a pressure to deliver, and that’s when Michael’s on-track antics began to straddle the line of acceptability. He’d already had a controversial collision with Damon Hill at the close of the ’94 championship in Adelaide but, in Michael’s defence, Damon wasn’t alongside his Benetton when they collided.

Not so Jerez ’97, another title-decider.

Jacques Villeneuve was almost taken out of the race when Schumacher turned into him in the closing stages. It was a deliberate piece of foul play that prompted former team-mate Martin Brundle to say on ITV: ‘You hit the wrong part of him, my friend.’ Schumacher was vilified for the clash, yet he seemed impervious to the public backlash. He maintained that Jacques had used him as a brake and he didn’t seem bothered that the FIA disqualified him from the world championship standings.

But, as distasteful as Jerez was, you could argue that Ayrton Senna was equally ruthless on track, so Schumacher wasn’t the sole catalyst for a change in driving standards. But Ayrton didn’t demand preferential treatment inside his own team; he was happy to accept equal kit to Alain Prost at McLaren. Schumacher, on the other hand, always sought the advantage.

Michael got first use of the spare car and first call on all development parts, and he demanded that his team-mates help him win at every turn. No one at Ferrari admitted to this favouritism, until they laid themselves bare at the 2002 Austrian Grand Prix, race six of 17 in that year’s world championship.

Race leader Rubens Barrichello was asked to let Schumacher win. Rubens fought the decision throughout the race, until the pair exited the final corner and swapped places in sight of the chequered flag. The backlash was immense, but Schumacher once again showed little remorse. ‘You need to maximise our opportunities,’ he said.

And then came qualifying at Monaco in 2006. This was the unequivocal low point of Schumacher’s career. He had no excuse and there was no hiding place for him. After setting the fastest time in qualifying, he deliberately crashed in order to prevent his main title rival Fernando Alonso from knocking him off the top spot. Never had the sport seen anything like it.

‘I really struggled with what he did at Monaco,’ said Mark Webber, who was so incensed that he demanded a clear-the-air conversation with Michael at the following race. ‘He was such a great talent that he didn’t need to bother with any of that.’

Indeed he didn’t. Schumacher was brilliantly fast and consistent, of the ilk we might never have previously seen in the history of the sport. His seven world titles and 91 victories are a testament to that breathtaking ability. But, like so many sporting greats, he didn’t know where to stop. Winning meant everything to him, not the means by which he achieved it.

Twenty five years on from his debut, as Michael continues to fight for life after his terrible skiing accident in 2013, there’s no danger of people not talking about him. And no danger of F1 forgetting his legacy.

Michael Schumacher: a life in F1

Active years: 1991-2006; 2010-2012

Debut: Spa 1991

First win: Spa 1992

First F1 title: 1994

GP starts: 307

Wins: 91

Poles: 68

Percentage of races won: 33.7%

Titles: 7

How Schumacher changed F1

Fitness: Michael was the first driver to make the link between fitness and on-track performance. He was fitter than everyone else. ‘A pain in the ass,’ said Gerhard Berger

Reward: Schumacher worked hard to become the best of his generation, then named his price. £60m a year? Because he was worth it! And others have followed

No.1 driver: Every point counts, so don’t allow your team-mate to take away world championship points. Toto Wolff knows it only too well. Ferrari could yet benefit in 2016

Rule-bending: Schumacher pushed the rules to the limit. His questionable calls at Jerez in ’97 and Monaco in ’06 led to the introduction of a driver steward at every race

Read more from the May 2016 issue of CAR magazine