► Seven testers, seven days, two cars, 5000 miles

► Is the 205 GTi more rewarding than the Esprit?

► Find out in our feature from December 1988

Seven CAR writers, on seven different journeys, subject Britain’s greatest supercar and the world’s top fast hatchback to a week-long marathon. They find out which goes best, and which survives best

Day one: Roger Bell goes to Cornwall, tackling moors in the rain

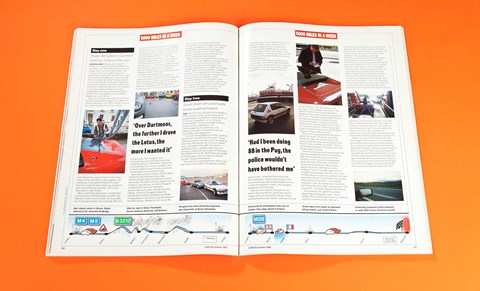

Moorland roads are great levellers in the wet. Had the B3212 that tumbles over Dartmoor been a dry rally stage, free from limits and traffic, the Lotus would have used its superior performance and grip quickly to humble the chasing Peugeot. As it was, the 205 GTi easily kept up. What little ground it lost on acceleration was soon regained through idiot-proof handling. Driving as briskly as prudence allowed, the Peugeot could be pushed amiably to its soft, understeering limit quite safely. Fully to stretch the more gifted Lotus called for greater skill and nerve.

Day one’s marathon chase to Dartmoor, Exmoor and Bodmin Moor for a game of chase had begun at CAR’s office car park. Our dawn escape from Earls Court highlighted the agility of the nimble Pug, close to the ultimate in city dodgems, as clearly as it betrayed the Esprit’s urban shortcomings of heavy steering, excessive girth and restricted visibility. The Lotus flounders in tight traffic.

Both cars felt frustratingly constrained on the tedious M4/M5 drag to Exeter, the 150mph Lotus more so than the busy 205, too fussily geared for fast cruising. We had ample time on this leg to rue the Lotus’s fuzzed rearward visibility, crude heating/ventilation, mean, reflective instruments and graunchy wiper. Still, for long-haul loping, I preferred the comfortable lie-back driving position of the Lotus, despite inadequate under-thigh support and a homeless left foot. The Lotus’s opulent cabin – the most professional yet from Hethel – also gave a better sense of well-being than that of the plasticky Peugeot. What it didn’t give was space for a holdall and a passenger.

On Dartmoor, the Lotus started to justify its supercar status, even though the agile Peugeot, its seat more supportive than the disappointing Esprit’s, kept pace. After we’d swapped cars to repeat the moorland dash, I was all for doing it again in the Lotus. The Peugeot was entertaining, but it was the Lotus that engendered lust. The further I drove the exciting Esprit, the more I wanted it, the more its addictive dynamism and ability overshadowed its shortcomings.

Extended over the moors, the Peugeot fulfilled its promise as a top-class sporting hatch, but it lacked the Lotus’s breeding. The Esprit would catapult out of hairpins, grip secure, while the Peugeot scrabbled for traction; the Esprit accelerated with clean, Ferrari-beating vigour, while the Peugeot’s steering kicked and writhed; the Esprit cornered with prodigious tenacity on a plane beyond the 205’s grasp. Briskly on the move, the responses of the Lotus were sharp enough to make the Peugeot feel a mite stodgy and deficient in bite. The nose-heavy 205 ought to have the better stopping power on wet roads, but the harder I used the Lotus’s brakes the more impressive they seemed.

Bodmin Moor we traversed in a trice on the A30 dual-carriageway; unleashed, the Lotus would have trounced the 205. Exmoor was sterner stuff. Again, the Peugeot held station on tight rain-lashed roads: light controls, friendly handling and giant-killing performance kept it in touch. It was here, though, that the Lotus finally snared my affection. As all-purpose transport, the Peugeot is the better car; on give-and-take roads, it can cover ground as quickly as anything on four wheels. It chased the Lotus with alacrity, but it failed to match the excitement generated by its quarry.

Day two: Gavin Green on autoroutes to the south of France

The Police pulled me over, barely 20 miles from home, as the Lotus and I powered down to Dover to catch the ferry to France. It was 6am, on an almost deserted M25. The jam sandwich Sierra pulled into my slipstream, still camouflaged by the darkness. His presence was announced by flashing blue lights, and high-beam.

‘You were doing 88 back there,’ said the policeman, on the hard shoulder. ‘If you keep driving like that, you won’t be able to drive this nice sports car of yours. Good day.’ Just when I thought my licence, spotlessly clean, despite eight years of driving in England, was to get its first stain, the Old Bill let me off. Had I been doing 88 in the Peugeot, you can bet our friend wouldn’t have bothered me.

The next twist came less than 10 minutes later, still on the M25. The speedo needle started to jump; then it started to bounce, right around the clock. And then the odometer stopped working. Here we were, trying to do 5000 miles in a week, and our corroboration of the feat the car’s odometer packed up. The only life coming out of the speedo after that, was an annoying tick.

Dover was enjoying a cloudless, but cool, sunrise. Just as the light started to turn from grey, to soft gold, the Lotus and the Peugeot – which, predictably, had enjoyed an uncomplicated run to the Kent coast – boarded the hovercraft St Christopher, destination Calais. The Lotus narrowly avoided grinding its nose on St Christopher’s ramp; the Peugeot sailed up nonchalantly.

France was chosen, as part of our seven-day marathon, partly because it made sense to log some foreign miles, and partly because Green was due to race at Paul Ricard, near Marseilles, that Sunday and needed to get there. The office long term test Cosworth Sierra Sapphire accompanied the Peugeot and the Lotus; road test reporter Brett Fraser and group art director Adam Stinson accompanied me. They also had the hapless task, the day after we arrived in the south of France, of driving straight back to England. Green would bring the Cosworth back, after the race.

Many cynics doubted that we’d even get to the south of France, given the transport. After all, no two cars have worse reputations for reliability than the Esprit Turbo and the Cosworth. ‘How is the Peugeot going to tow both cars,’ the sceptics were saying.

On the long autoroute grind south, the Esprit proved better than I’d expected. Mechanical drone was almost non-existent; road noise well suppressed, given the size of the tyres, and their closeness to the driver. Wind noise, appalling on the old Esprit, is still a problem: and no wonder, given those unsightly panel gaps. Yet the Lotus was not the talkative, wearing companion I had expected. I drove it most of the way south, and arrived at my hotel – just outside Aubagne, after doing the final stint from the Fraser/Stinson hotel in Brignoles in the Cosworth in better shape than I feared.

Annoyances included the Lotus’s appalling pantograph wiper, which judders its way through its arc in anything less than torrential rain; the car’s wandering, unsettled behaviour on those grooved sections of the autoroute either side of Paris, designed to kill unsuspecting motorcyclists; the uncomfortably close gearlever, necessitating a strange contortion of the hand; the terrible glare picked up by the rear perspex screen when the sun is behind you (rendering the poor rearward vision even more useless); the car’s inclination to tramline badly under brakes; the poor ergonomics; the slow refuelling process; the awkward offset fatigue-inducing driving position; the baulky fourth-fifth gearchange (it would not be difficult to wrong-slot, and get third by mistake — with a subsequent undesirable effect on valve life); and the headlamps which, although powerful enough, tend to shake and vibrate like the cigarette of a nervous old man.

You are also constantly aware that, although not exactly a tiring companion, the Lotus is never truly relaxing: it’s too nervous, too noisy, too much like a restrained racehorse just waiting for the opportunity to break free of the autoroute’s constraints.

When it came time to share life with the Peugeot, the relationship inevitably proved less stimulating, but less taxing. You could tote up the miles, on the long deserted straights, with your brain more or fess in neutral. In the Lotus, you have to concentrate. Not that the French car is a refined motorway performer. Its ride can get unsettled (more so than the Lotus’s); it has quite a lot of wind noise (although less than the Esprit); its steering has far more wrist-jarring kick-back than the better-damped Lotus’s; and if you stray over 90mph, the Pug’s engine complains. In the Lotus, the barrier just passes by.

Nonetheless, if you want to ply the autoroutes of France, or the motorways of Britain, my advice is not to buy either car. A regular, bread-and-butter Cavalier L will do a much better job. And so, for that matter, will a Cosworth Sierra Sapphire.

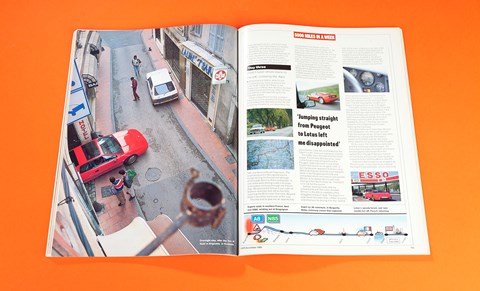

Day three: Brett Fraser drives back to the UK, crossing the Alps

A mysterious siren, akin to an air-raid warning, woke us early in the rustic Hotel Fabre de Piffard, in the sleepy town of Brignoles. Washed, fortified by fresh bread and strong coffee, Stinson and I left the hotel psyched up for the long trek ahead. It was a beautiful morning, southern French sunshine already burning through the October mist. We were on the Aft the Autoroute Provencal, our destination the N85, the famous Route Napoleon. The road along which Bonaparte led his troops during his triumphant (though short-lived) return to Paris and power, is one of the best driving roads in Europe, and snakes viciously through the French Alps. We planned to follow it just north of Sisteron and then fork off on the N75, rejoining the 85 to enter Grenoble. Beyond there it would be autoroute all the way.

This trip was to give me an opportunity not granted many 25-year-olds, the chance to drive a true-blue supercar. As one more used to frantic hatches, the Esprit was a bit of a culture shock. It’s like strapping yourself into a capsule. You sit so low, and the doors and facia rise so high around you, that you feel much more enclosed than in lesser machinery.

Jumping straight from Peugeot to Lotus left me disappointed, initially. Whereas the 205 is eager (almost too eager) and willing at all times, at low to modest speeds the Lotus feels leaden and cumbersome. As I followed Stinson off the autoroute and onto the secondaries, I also felt intimidated by the Esprit’s width and poor rearward visibility.

The traffic soon thinned and the climb began. For the first 20 miles or so, I was content just to tag along behind the Peugeot, learning what I could of the Esprit’s behaviour as we sped north. It quickly became apparent that the Lotus demands that you work for your rewards, while in the Peugeot practically any competent driver can jump in and go fast. Stinson is no Ayrton Senna, yet I was having to try hard to keep up. The Esprit is no car for the novice.

Narrow, twisting roads and my unfamiliarity with the Lotus allowed Stinson in the 205 to overtake a few stragglers and pull clear. The Esprit is a wide beast (broader than a Merc S-class), and when you’re driving it on the ‘wrong’ side of the road, unless you can see a fair way ahead, you daren’t start edging out for a peek. During my efforts to catch up, I began to enjoy the Esprit and my confidence grew. It needs to be driven hard before it reveals much advantage over the Peugeot. The faster it goes, the sharper its responses become and the more spirited it seems. And it has such phenomenal acceleration it simply explodes between bends and past other cars. The 205 was rapidly caught, so I began hanging back to do it all again.

The Esprit corners much faster than the Peugeot, too. Where you’d hesitate in the 205, and perhaps dab the brakes, the Lotus will simply sail round. On one or two tight, loose-surfaced bends, the Lotus twitched a warning with its tail and I heeded its advice – the Alps are a bad place for the inexperienced to start learning the hard way.

Roughly half way to Grenoble, Stinson and I swapped cars. Although quicker than the average driver, Stinson was soon left trailing, uneasy with the Esprit’s power and limited visibility. His smile returned when he got back in the Peugeot.

All too soon, the mountains were over and the motorway tedium began. On those Alpine passes, the Esprit shone and proved appreciably faster than the upstart from Peugeot. But you have to concentrate and you can have nearly as many thrills for half the effort in the 205.

Darkness descended as we slogged up the toll roads. It was then that I noticed the Esprit’s speedometer, which had long ceased working, had broken its needle. Fortunately, the French policemen who stopped us at the last toll booth before Calais didn’t spot this deficiency. They didn’t explain why we’d been pulled over. Perhaps the combination of flash car and scruffy young driver was irresistible.

By now our 21.45 ferry was long gone, lost to the mountains, the police, a few photographs and a long, long journey. Fortunately there was another at 23.30, and we were back in fog-bound Blighty in the early hours of Friday morning, ready to hand on the batons to the next members of our relay team.

Day four: Steve Cropley concentrates on winding Welsh roads

Picture taking is the enemy of all progress, I decided in the dark, as I waited outside my Gloucestershire place at 6am for the two cars to arrive. True, CAR’s own smudgers are agreeable fellows, but on this, day four of our zero to 5000 miles dash, when the job was to put 715 miles under the wheels of each of two cars, much of it on the sinuous roads of Wales, vistas through viewfinders were far from my mind. Time is distance.

Still, it was a pleasure to see my driving companions, Mr Newton, photographer, and Mr Elsden, art director, when they turned up at 6.13am. Best of all, it was too dark and foggy to take pictures. We elected to head west to the end of the M4; that would make an easy 150 miles. Here began the hard driving: along the slow A40 to Haverfordwest, then out to St David’s Head (a veritable photog’s paradise), then to Fishguard, and up along the west coast, past Cardigan on the A487 towards Aberystwyth.

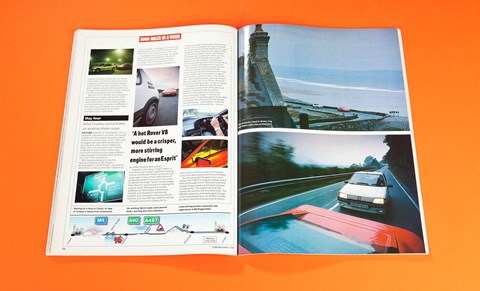

I started in the Lotus. I hadn’t been in one of the new models, apart from taking a short and frenetic thrash at launch time a year ago. It was a most odd mixture of properties excellent and awful. You have to admire the shape. Given his low budget, Peter Stevens’ achievement in making the angular early-’70s Esprit into a lithe, professional ’80s shape, is enormous. Visibility and headroom and driving position are now beyond serious criticism—and this is an over-fed lad of 6ft 2in talking.

Plaudits also to the chassis for its handling/roadholding/ride compromises. Lotus, which has been telling us (to plug its active ride) that steel suspensions can’t be good in every way at once, gets closer and closer to disproving its own theory. The easy high-speed gait of the car and its wide-tracked stability even under extremes of acceleration or braking or cornering load speak for the thousands of hours’ chassis development it has had.

But frankly, the engine is past its time. The lack of crisp and instant throttle response just can’t be tolerated any more. I can’t believe we once said this engine was lag-free; it just isn’t true. The 2.2-litre twin-cam is still powerful, but that doesn’t make it adequate. A hot Rover V8 would be a more stirring power unit for an Esprit.

The test car’s gearchange felt more notchy than I remember of the previous models. I hated the way the doors wouldn’t open wide (a car this low is difficult enough to get in and out of, without that). I hated recognising old ARG switchgear. And the fact that the speedo had packed up and made a noise like an over-wound clockwork toy— was an awful echo of the fact that not long ago Lotus cars were presumed to be unreliable.

Summing up the Peugeot is so much easier. The 1.9 GTi is leagues ahead as the best of the superminis. The small size and superb shape make a Golf seem old and cumbersome. The supple, poised ride makes the rest feel like wheelbarrows. The effortless steering and sweet gearchange continually delight you, no matter how far you drive. And the torquey engine (which can deliver flashing performance without exceeding 4000rpm) is a far better advertisement for the in-line four than Lotus’s higher-developed unit.

The big issue, though, is how these entirely different cars seemed, one after another. The Lotus was comprehensively the faster on even the most kinked and curvaceous road, but to extract its full potential you had to turn off the radio, take a deep breath, settle yourself comfortably and concentrate single-mindedly on placing the car’s wide body in corners with racetrack accuracy, and on being in the right gear at all times. One wrong cog could cost you 200 yards, such is the depth and breadth of the lag.

The Peugeot, after the Lotus, always seemed light, effortless and surprisingly fast. In no way was it disgraced by expensive and specialised company. The Lotus, after the Peugeot, was bulky and heavy, complex and challenging. The Peugeot is the better car for 95 percent of Britain’s drivers. The Lotus is better and more satisfying, once you’ve I earned the techniques that 95 percent of the population don’t know about.

As examples of their types, the cars were very uneven. The Peugeot was a delight; for me the pinnacle of hot hatchbacks, The Lotus – for all its fine chassis and beautiful body – drove like a car whose best years are past. I found myself hoping this was not the best the new Lotus company could do.

Day five: John Lilley heads north and takes in Edinburgh

At 40mph, the loudest noise in the Lotus – I discovered after leaving the Earls Court car park at 7am – came from the mechanical speedometer drive as it chewed up the broken instrument entrails. I endured the racket for two hours on the trek to [an Fraser’s house near Diss, Norfolk. (It was there that the vice-like fingers of Fraser’s son Anthony extracted the offending worm of metal which, to our general amazement, proved as long as the car.)

It was on those early morning roads that I kept gentle station with the Peugeot – ferried by a friend who joined us for this Scottish leg – until an energetically driven 928 began to swallow A11 traffic in prodigious gulps, I tagged along for a while, the Lotus’s third and fourth gear overtaking wallop matching the pace set by the Porsche. But l let it go in the end, my stomach for the size of the overtaking bites failing rather than the Esprit’s muscle.

Heading west from Diss, onto the four-lane Al, I stuck with the Lotus, exploring its user friendliness in multi-lane drudgery. Forget handling, forget performance, rearward vision is what counts here, and ride, creature comfort, ambient noise, quality of stereo sound. It looks a pretty blinkered piece of kit, the Esprit, but I found outward vision only marginally more limiting for lane hopping than the average saloon’s. Aided by large and essential and excellent ’89 spec mirrors, this car offered no dangerous blind spots, care being needed only on the nearside rear when overtaking.

Generally, the driving position for the long haul is relaxing, the seat itself being the weakest ingredient. It needs more substance around the bum, and more emphatic lumbar support. However, with elbows resting on centre console and door arm-rest, and hands falling onto the wheel at a quarter past nine position, the miles can be racked up for several hours before you feel the need for a stretch. Ride is a pleasant surprise, comfortable if firmish, the engine noise well suppressed, but motorway concrete communicates tyre slap and roar very faithfully. And the Lotus’s sound system provided much richer companionship than the Peugeot’s could muster. Worst motorway irritant in the Esprit seems footling, but isn’t: the indicator stalk won’t self-cancel after lane changing.

I swapped with Fraser at Scotch Corner. Here was a chance to fly, literally. The A68’s sharp peaks will put air under all four wheels at perfectly modest speeds. Everything is lighter, easier, in the 205. Here is a car that lives on its nerves, its throttle hair-trigger keen; on the twists and swoops of the A68, the 205 scampered and lunged, its safety margins so high that no averagely sane driver need feel anything other than pleasure. On later M90 multi-lane driving, the Pug’s more compliant ride and generous bushing made it the quieter cruiser, its all-round vision, despite little mirrors, excellent.

At Jedburgh, A68 exhilaration was dampened by our awareness that the Lotus’s oil pressure needle was flirting with the red part of the gauge. We had too much oil pressure. So Fraser called Martin Cliffe, project manager on the Esprit Turbo engine from 1979-82, and he suggested we limit ourselves to 3000rpm, just in case. This was not good news. But blowing an engine was not a welcome prospect, either.

I switched back to the Lotus for the drive through Edinburgh city centre. It was here that the car’s hidden forward extremities became worrisome, especially the nearside front corner, in narrow lanes and during give-and-take city driving where our eyes were at everyone else’s bonnet and boot levels. Worst irritant here was the ludicrously stiff accelerator pedal; the clutch was fine, the brakes a fraction too light. (The 205’s clutch and brake are well weighted, but the accelerators too lightly sprung.)

Out of town, over the Forth Bridge, we pressed on up the A9 into the evening mist, to find safe harbour for the night at Blair Atholl, 627miles from Earls Court.

Day six: Ian Fraser heads south, but cannot drive the Lotus fast

Grey dawn and dark thoughts. But at least the temperature was well above zero as I gingerly roused the Esprit’s engine and held my breath, waiting for an oil line to split or the filter to rupture as the thick lubricant accelerated the pressure gauge needle near the red with only 800rpm on the clock. We had diagnosed a jammed oil-pressure relief valve the day before and were worried to distraction that excessive pressure might dump the entire lubricant supply onto the roadway (or, worse, over the hottest bits of the turbocharged engine) in one massive, destructive splurge. So it was going to be a Sunday of religious adherence to 2800rpm to keep the needle out of the red.

Out of Blair Atholl and back onto the excellent A9 without having even glimpsed the Duke of Atholl’s castle, or any of his private army that we could tell. Sitting low in the Lotus, brushing aside the thick mist, made me think imaginatively of the red deer herds in the Highlands. Would the Monarch of the Glen come through the windscreen or go clean over the top if I took his feet out from under him?

Definitely no space for a stag and me in the Esprit. In fact, I struggled to find accommodation for a few tapes, a map book, travel sweeties, a small bag and my jacket. Had a second person been travelling with me, the latter two items could have been relegated to the boot. Because I’m fat and have big feet and my back hurts most of the time, getting into and out of the Esprit was a graceless process, aggravated by the right-hand handbrake and a door that only half opens. More footwell space would have been good for the size 10s, but the seats suited me well enough and gave sufficient support over long stretches at low revs.

Steering was wonderfully high-geared and responsive, the brakes assured, the clutch light and progressive. Gearchange was better than remembered but still not silky like a Ferrari’s. And the suspension was wonderful, firm and comfortable, well controlled and alert in a supercar’s toughest role: travelling at low speeds.

We changed cars before we got to Inverness. John Lilley took the Lotus and we headed for the saddest place in Scotland, Culloden Moor. The Peugeot felt lofty and spacious after the Esprit, and its ride less well controlled. Through Inverness and down the Great Glen, with hart an eye peeled for unusual happenings in inky Loch Ness. Very agile car, this Peugeot, with reasonable gearchange not used too often because of the immense flexibility of 1.9 litres in light, compact package. Very habitable cabin apart from awful boom period from the exhaust around 65 through 80mph.

From Fort William down to Glasgow via the rough old road around Loch Lomond. Typically good French suspension showed to advantage. Ever onwards towards Penrith to the A66, thence Scotch Corner to change back to the Lotus for the run down the Al to London.

Neither car was the ideal long-distance tourer. The Lotus Jacked cabin space and convenience despite its hefty external dimensions, and its performance was peaky. Conversely, the Peugeot was spacious enough but its suspension was not ideal, joggled uncomfortably at times and the boom was tiring. But the engine was lusty and responsive.

Woke up 3.30am next day with a shattering neck-and headache that had unquestionably been caused by one or the other of the cars. Cannot be sure which, but the finger points towards the 205’s sometimes joggling ride. Neither car really fitted the bill for long-distance touring.

Day seven: Mark Gillies loops Millbrook’s bowl and handling circuit

Final day, and we ferry the cars up to the Millbrook proving ground in Bedfordshire. Perchance, we happen to meet a Lotus test driver, doing work on a US Esprit. We ask him about the oil pressure gauge. ‘That’s the press car, isn’t it?’ We told him it was. ‘Oh yes. It has a faulty gauge. Ignore it.’ Fraser and Lilley, who have just endured two days of restraint, will later curse that gauge.

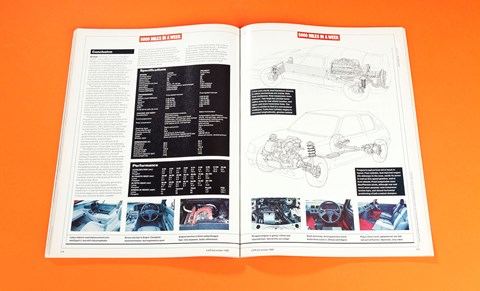

On the mile straight and high-speed banked bowl, there’s no real contest. The Pug performs astonishingly well, but the Lotus is from a different solar system. Any car which covers 0-60mph in 5.3sec, 0-100mph in 13.4sec and whose fourth gear increments from 40-60mph to 70- 90mph are under 5.0sec, is phenomenal.

It’s not easy to extract that performance, though. Taking fourth and fifth gear figures from just below 20mph, the Lotus responds as willingly as a sulking child. In fifth, where the tacho shows just 900rpm, you have to feather the throttle sympathetically until the engine picks up. Standing starts require brutality and delicacy: brutality to keep the crank spinning at 6000rpm when you drop the clutch, delicacy to avoid too much wheelspin. On one of our four runs, using

500 revs too many, the Lotus snaked up the first 50 yards. Too few revs, and the turbo motor will bog down, off boost. Once you’re away, though, and once beyond 4000rpm, acceleration is stunning – like Captain Kirk winding up the warp factor on the Starship Enterprise. It’s quick, the Lotus, the sense of speed enhanced by the proximity of your backside to Millbrook’s surface and by the seemingly unending power curve. Standing start times are aided by the gearchange, which is fast and fool-proof.

On the bowl, the Lotus will run a complete lap at more than 153mph, at which speed you’re sacrificing about 5mph to turn-in tyre scrub. It’s not a particularly pleasant experience, for the Lotus squirms a little over bumps as you restrain its tendency to edge up towards the Armco-retaining wall. Above 140mph, too, the rear nearside edge of the bonnet lifts, which is less than reassuring. But later on, running at 130mph for 40min, you can’t fail to be impressed by its high-speed stability and superb performance.

The Peugeot is easy after this one. Part of its charm is that it’s simple to extract the full performance. Around the bowl, the car feels secure while running at 124mph, its tacho needle nestling in the red sector at 6400rpm There’s no fuss, no drama, no need to hold the steering wheel firmly. On the mile straight, engine flexibility makes the fourth gear runs a doddle. There’s ready power from as low as 1000rpm, continuing well past the 6000rpm start of the red sector. Although there’s nowhere near the top end grunt of the Lotus, the Pug is more accelerative from 20-40mph in fourth and fifth, as well as from 30-50mph in top. Thereafter, I’d prefer to be in the Lotus if I’d slightly misjudged an overtaking manoeuvre while a 38tonner was bearing down on me.

Standing starts are simple in the Peugeot, too. Burning enough rubber to push up Michelin’s share price, we recorded 7.6sec for 0-60mph. And using just 2500rpm we reached 60mph in 8.0sec accompanied by just a chirrup of wheelspin. I’d lay bets you couldn’t get within 2.0secs of its optimum time if you tried the same approach in the Lotus. We were astonished by the Pug’s marginally superior stability on the straight.

But despite its straight-line performance superiority, the Lotus was only fractionally faster around Millbrook’s tight and twisty handling circuit. Both Richard Bremner and I, swapping cars, could eventually catch the Pug up in the Lotus: but the extra effort required was enormous.

We immediately adapted to the Pug’s brand of in-car entertainment: a fluid, safe, communicative chassis which changes direction neatly, purposefully. Near neutral, the only handling flaw is too much steering self-centre which causes your shoulders ructions. The Lotus, though, is tricky and its slight advantage around the handling course seemed down to far better brakes and the extra grunt you can use between the corners.

The corners. Theoretically, a mid-engined layout, wide tyres and a race-developed chassis should mean sharp turn-in, near neutral handling and immense grip. Well, the Lotus washes wide on entry to bends, then oversteers if you try to neutralise the understeer either by lifting off or applying power. And you have to be quick to catch the tail. It doesn’t like changing direction, either. After 10 laps, you climbed out of the Lotus relieved you hadn’t stuffed it, but stayed in the Pug, grinning.

Conclusion

Seven drivers; seven different routes; many different opinions. The Peugeot comprehensively beats the Lotus in town and, although its superiority is not as marked as we had expected, on motorways or autoroutes. It is a more relaxing car, a quieter car, an easier car to live with, and drive. A more refined car, too, given its much more progressive power delivery, the better weighting and feel of its controls, its overt modernity (compared with the slightly old-fashioned Esprit) and its more predictable handling.

The Peugeot also proved less troublesome, as we expected. Yet the Lotus stood up to its 5000miles-in-a-week ordeal better than most of us feared. Its only faults concerned the instruments: the speedo stopped working on day two, the oil pressure gauge read too high from the very beginning, and the handbrake warning light failed on day three. While a trio of faults hardly give the Esprit a clean sheet, it’s significant that there were no mechanical problems. The Lotus never missed a beat. Neither did the 205.

The Esprit used more oil than the Peugeot – three pints, as opposed to one – and, predictably, it also used more fuel on the identical routes. Its average petrol consumption, after 5022 miles, was 20.49, as opposed to the Peugeot’s 27.56mpg.

The test proved to us that the Peugeot is the best fast hatchback you can buy. Its daintiness of line, its willingness to rev, its nimbleness, and its sheer manoeuvrability, put it ahead of its nearest hot hatch rival, the considerably more expensive Volkswagen Golf GTI 16V.

The Esprit is not the best supercar. It lacks two crucial ingredients. Its engine, although able to deliver the ultimate wallop of sweeter, larger, non-turbo units, has nothing like the flexibility, the throttle response, or the music of the likes of the Porsche 911 or Ferrari GTB. It also lacks the external beauty: its body is not as well crafted (witness those awful panel gaps), nor as distinctively styled. Paint quality is not of the finest, either: the Lotus had a number of stone chip scars at the end of the seven day drive.

At the end of the week it was generally, but not unanimously, agreed that the Peugeot was the better car. Its ability is far more even; it has far fewer flaws. To boot, it is more responsive, safer handling (and, in the view of some testers, a better handler, period). Its performance is so much more accessible than the Lotus’s. It is there to be taken, to be enjoyed, to be exploited, like an easily reached yet delicious sweet. You do not need great skill to discover the appeal of the Peugeot (or have to accept the many compromises that surround the Lotus).

And yet, in the right hands, the Lotus is still the more exhilarating car – and by a wide margin. Faster on winding secondaries, too (a fact that, before this comparison began, many of us seriously doubted). This extra stimulation is the great trumpcard that the Lotus can play – providing the player is good enough.