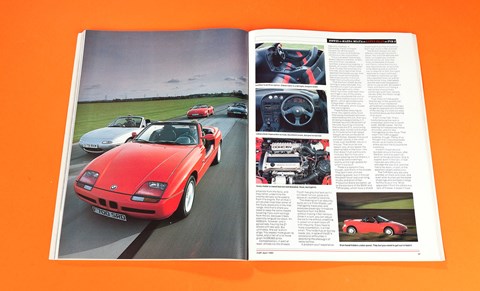

Suddenly, sports cars are here again. Not trumped-up shopping trolleys, super-fast coupes or chop-top saloons, but real, follicle-wrenching rag-tops to succeed the MGB, the Triumph TRs, the Elan and the Spiders from Fiat and Alfa. Rorty, soft-roof two-seaters with their low-set, legs-ahead driving stance, spring-loaded throttle response, ultra-quick steering and that bundle of compromises familiar to anyone who’s spent a week of winter behind the wheel of an MGB.

That’s what you expect of cars like this, at least. These are our last memories of a strain of car whose development stopped a decade ago, when two-seat sportsters were overtaken by economies of scale, mass marketability and hordes of GTIs. But now, 10 years on, we’ve a right to expect more.

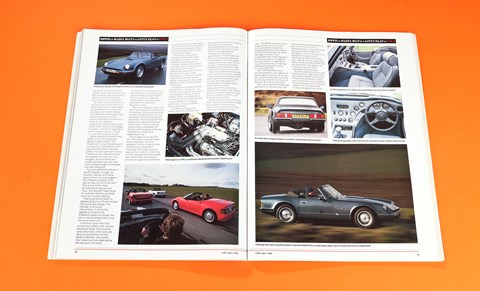

Vastly improved dynamics, better reliability and superior convenience are just some of the desirables. So are decent styling and entertainment value — these, more than anything else. We already know from previous drives that the Lotus Elan, Mazda MX-5 Miata, BMW Z1 and TVR S promise these qualities. But after a week and thousands of miles we know that they deliver far more than that.

They’re technically compelling, an important element in the sportster’s appeal. They fascinate like no tin-top does, not least because soft-tops and two seats or not, their makers have taken very different roads to arrive at answers. Consider these disparities. Three of the cars have separate chassis and plastic bodies, only the Mazda having a steel monocoque body. Three are rear-drive, the Lotus alone in having front-drive and an east-west powertrain, as found in the bulk of today’s cars. But as we shall see, Lotus has worked hard to hone this configuration for sensational results on the road. Engines? We’ve got a V6, a straight six, and a pair of twin-cam 16-valve fours, one blown, one not.

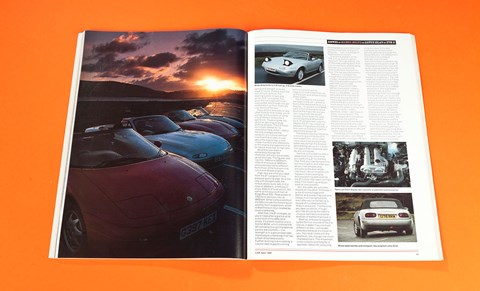

Superficially the simplest is the Mazda. It is closest in concept to the MGB, though without the crudity. This is deliberate. First, the Miata is meant to be a budget sports car, and that means keeping costs low. And second, it was inspired by European, and in particular British, sportsters, machines it unashamedly apes, right down to the mock-Minilite alloys.

So we have a fairly straight-forward mechanical layout, though there are plenty of subtle refinements to endow the car with manners that would be alien to MG drivers. The engine is mounted in-line and well back in the body for good weight distribution (it works out at a promising 52 percent front, 48 percent rear) and bolts directly to the transmission which sends power via a propshaft to the differential.

Suspension is by unequal length wishbones all round, the rear pairs bushed at their outboard ends to produce toe-in during cornering. The dampers are concentric within coil springs, to minimise friction, and there are anti-roll bars at both ends. Long wheel travel, particularly at the front, is a feature, as is geometry to minimise handling quirks.

The suspension is mounted on sub-frames rather than to the body direct in an effort to improve rigidity and refinement. To the same end, Mazda has developed what it calls the power plant frame, a pressed aluminium component that’s bolted to engine and front sub-frame and runs to the offside of the propshaft to link with the rear sub-frame and the diff, creating a rigid, unitary powertrain. Amazingly, it weighs just 11lb. Apart from its strengthening role it is intended to prevent snatch and shudder under acceleration and deceleration. Steering is by rack and pinion, as you’d expect, but it’s assisted, which you wouldn’t. This allows just 2.8 turns lock to lock, despite a tight turning circle. Brakes are disc all round, vented at the front.

The Miata’s twin-cam 1598cc motor comes from the 323, but it’s been tweaked for its sportier role, modifications including tuning and balancing to stretch the rev range to 7200rpm, slimming the flywheel for sharper response and, get this, rounding off the cam cover casting to give the unit a European look. Power works out at 115bhp at 6500rpm and there’s a rather less impressive 100lb ft of torque at a barely less frenzied 5500rpm. This is clearly a rev-to-the-heavens motor. Fuel is sequentially delivered by L-Jetronic injection, and sparks arrive without recourse to a conventional distributor. The manifold tube lengths have been equalised as far as possible and the entire exhaust system, which includes a three-way catalyst, is of stainless steel for lightness and long life.

Longevity should be a feature of the Elan, too, with its plastic body panels. These aren’t load-bearing, because the structure’s strength is drawn from a fabricated backbone chassis, a feature of the original Elan. The chassis provides a subframe for the engine – detachable, so that the powertrain can be dropped down for major work – and the suspension pick-up points. In tandem with the reinforced floorpan, it makes the Elan shell a stiffer structure than the average hatchback’s steel body.

Given Lotus’ history, both in production cars and motor racing, it would be a surprise to find anything other than double wishbones lurking in each wheel-arch, and that’s exactly what you get. At the back end are arrangements very similar to the Excel’s, consisting of a wide-based lower wishbone for accurate wheel control, upper links, coaxial coil springs and dampers and an anti-roll bar articulated via drop links to the chassis, enhancing its effectiveness.

Up front we again have unequal length wishones, the same spring damper arrangement and a similar anti-roll bar lay out. What’s unusual is the pair of so-called rafts to which the wishnones are mounted. They’re claimed to take front-wheel drive one step beyond, and in Lotus’s eyes, justify the abandonment of rear drive for its sportster, something many tail-slide tearaways can’t stomach.

Essentially the rafts provide an extra link between wishbone and chassis frame to control the wheels. It allows the wishbone brushes to be very stiff for accurate wheel control without transmitting road noise into the body structure, permits a very low castor angle to minimise change in the steering effort a you swivel the wheel, and helps expunge torque steer.

The engine comes from the Isuzu, and though Lotus had a say in its development and some detail design – such as reshaping the intake plenum so that it would clear the bonnet – the basic design is Japanese. Lotus will earnestly tell you that this engine was chosen on merit and not because it comes from some arm of GM, but its hard to imagine the Elan powered by, say, a Fiat engine.

Whatever the politics, there’s no denying that it looks good on paper. An iron-block, alloy head twin-cam 16-valve, the Isuzu motor squeezes 130bhp from 1588cc in normally aspirated, injected form and, as tested here with an IHI turbocharger and an intercooler, the figure swells to 165bhp, delivered at 6600rpm. The torque figure is strong, too, at 148lb ft, and the peak arrives earlier than for the Mazda, at 4200rpm. The Isuzu unit is mounted across the engine bay, of course, and comes to Lotus complete with an end-on five-speed box.

Other details: brakes are disc all round, the front rotors ventilated, the steering is rack and pinion assisted giving 2.9 turns lock to lock for a not too compact turning circle. And the Elan’s weight is distributed 64 percent front, 34 percent rear. You might expect a less than favourable weight spread for the TVR, too. The 2.9-litre Granada motor, and its transmission, lie well within the front half of the car, yet the axles share the load equally. Open the bonnet, and you realise that the Ford lump sits well back in the shell, forcing the gearbox into the cabin where it separates you from your passenger.

Of course, the TVR has a separate chassis. It comes from a long line of British cars, not all of them TVRs (remember Gilbern? And Clan?) whose creators hit upon the idea of taking a stock engine, stuffing it in a tubular frame and clothing the whole in a shapely (or sometimes not) envelope of glassfibre. If this suggests crudity, then so be it – the TVR is an old-school roadster.

It’s a surprisingly effective one. Like the best sportsters, double wishbone suspension features, though only at the front. The rear wheels are located by trailing arms, and coaxial coilspring and damper units are used all round. There’s a solitary anti-roll bar up front. The steering system is rack and pinion and — a surprise, this, given the car’s apparent bulk — unpowered. And though you get vented discs up front, there are only drums at the rear.

If you drive a Granada, or any other Ford for that matter, you’d wonder at the wisdom of using one of Henry’s motors for a sports car. These engines are about as sporting as drug-stuffing athletes. The 2.9 motor isn’t much altered for its installation here, either — about the only changes are the adoption of a tubular exhaust manifold that snakes its way about the engine bay, a new intake manifold and alterations to the engine management chip to induce more fuel at high revs.

What this also does is completely change the character of Ford’s old plodder, as we shall see, The figures look like this: 168bhp at 6000rpm, 1721b ft of torque at 3000rpm, characteristics rather different from those of the fast-spinning Lotus and Mazda engines.

High revs are what you need from the Z1’s engine if it’s to produce gushing urge. As is the way with straight sixes, the torque peaks quite late, in this case at 4300rpm, where you’ll enjoy 1641b ft of twist action, the same as for your common or Kings Road 3251, Peak power of 170bhp is identical, too, at 6800rpm, Other carry-overs from the 325i include the transmission and the front suspension, which is MacPherson strut located by lower wishbones.

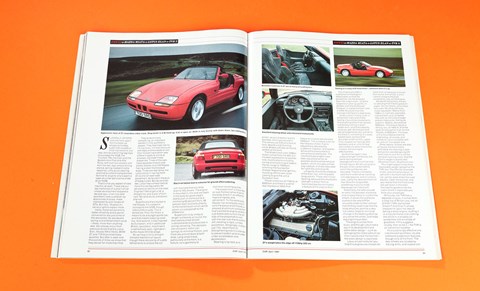

After that, the Z1 diverges, as you’d hope after a glance at its outlandish silhouette (and price). It’s plastic-bodied (not a first for BMW, which clothed the M1 similarly) though the external panels are cosmetic — the strength is in a galvanised steel monocoque underbody that has a floor of bonded plastic. Further bracing is provided by a tubular steel support running behind the facia and an integral roll-over hoop that runs up the pillars and across the top of the screen.

The Z1’s engine is mounted well back in the car — almost a foot further rearwards than in a 3-series to achieve what BMW calls a front mid-engine layout. Scoff at this if you like, but you can’t argue with the weight spread, which loads the axles almost equally at 49 percent front, 51 percent rear. Like the Mazda, the Z1 has a rigid link between the gearbox and diff, in this case via a torque tube that sleeves the propshaft.

The torque tube also serves as a mounting point for the Z1’s rear suspension, which is far more advanced and promises better results than the 3-series’ semi-trailing set-up. It’s a multi-link layout that in essence uses double wishbones. Not that all this techno-talk is uppermost in the mind when you confront a Z1 for the first time. First, you’ll be trying to find out how to get in, and when you do you’ll be amazed and amused as the door drops into the sill. So will anyone who happens to be passing by. Actually gaining admission to the Z1’s coal-hole cabin isn’t too easy if the hood’s up and you want to look graceful.

Still, the seats are welcome reward for the effort. Trimmed in a mix of camouflage print leather and suede, they cup and caress in all the right places, even after you’ve racked up a couple of hundred red-mist miles in one burst. The first time you take up station, though, you’ll be struck by the cabin’s unusual architecture and the swathes of leather that cover it.

Start up, and you’re regaled by the familiar sounds of the 2.5-litre six. It doesn’t sound much different at idle —just louder, probably because it’s closer to you, You’re at home with the gearlever, too, though not much m pressed by it. The movement is too rubbery and long for a sportster. Move off, savouring the progressive clutch and oiled throttle movement, and you’re struck by well, a shortage of eagerness and oomph.

This isn’t a problem in the TVR. Fire up and you get an explosion. Or to be precise, lots of little ones woffling down that tubular manifold, reverberating beneath you, and issuing seductively from that twin tail pipe. This car sounds powerful. Getting in it is easier, too, though there are pitfalls for the unwary— those doors aren’t very long, and getting your feet past them calls for deft legwork. Once in the TVR’s leather-lined world — there’s more of the stuff in here than there is in the BMW — you’re reminded of the olde worlde sports car driving stance. It means legs stretched, bum close to the ground and not much elbow room on the right because the wheel is so far over.

The controls — clutch, gearlever, wheel — are heavy in action, but compliant. The throttle response is marvellous. A soft prod, the warbling deepens and the S moves with the assurance that only a fat torque curve can deliver. There’ll be no bogging down in off-cam calms with this one. The Miata, on the other hand (and we refuse to call it MX-5, the car’s official badge in Britain, it’s so soulless) is the very antithesis. Its controls move with the lightness and ease of a Nissan Micra’s. The difference is that there’s an overlay of delicate, machine-tool precision in their movement, too, especially in the gearchange. Its little engine ticks over crisp and quiet, jumping eagerly if you tap the throttle. It sounds keen, but not rubber-wrenchingly potent.

If snicking home the controls is easy, so is getting in. Yes, the seats are lower than in a Fiesta, and you must extend your legs more, but this car is as easy to enter as the Ford. Your mother would like it. She’d probably turn her nose up at the depressingly extensive acreage of vinyl, though, just as we did. It shrouds the dash, itself a very simple structure, the doors and quite a lot more. Combine this with black seats whose cloth covering looks to have been hijacked from a ’74 Datsun Cherry and black as coalite carpets, and you have a cabin that looks cut-price. Still, the Mazda feels peppy and fun.

After this trio, the Lotus feels more grown-up. There’s not much of a wrestle getting in, apart from the appalling door locks and handles, though you do plunge rather low. You’re confronted by a modern, well-stocked facia that’s nicely sculpted. Not that this hits you first. No, ifs the huge distance between you and the base of the screen that surprises. At first it’s slightly intimidating, especially since you haven’t a hope of seeing the bonnet, so steeply does it dive. That you sit a bit too low in the car doesn’t help here, either.

If you’ve ever experienced a ’60s roadster, even for a couple of hours, you’ll probably remember the way it quivered and shook over bumps. In the Lotus, it doesn’t matter whether there’s canvas or firmament over your head, this car does not shudder, And another bonus -you enjoy a supple, controlled ride. Occasionally it causes discomfort, but that’s mostly at suburban speeds, and the cause is simply the firm springing and damping, necessary for a 140mph car.

The TVR is stiff-sprung in the town crawl, too. Most of the trouble is at the back end, where the rear wheels fall into bumps with seat-squashing resolve. Add speed, and if the road’s poor you often feel a sharp vertical jerking as the springs fail to absorb.

But this isn’t so upsetting that you don’t enjoy the car. Its allure is strong enough to overwhelm another drawback that dates it, and that’s scuttle shake. Hit really rough blacktop, and you’ll see the front of the car, from A-posts forwards, twisting relative to the cockpit.

There’s bulkhead shudder in the Miata, too, but it’s fairly rare. Mostly, it’s a taut car. There’s a slight decline in rigidity when the hood is unfurled, and you sense that behind you, when the back occasionally quakes.

You get the same sensation in the Z1, too, as if the rear wheels are fighting each other for control of the structure. It’s not a serious flaw, but it certainly separates the BMW from the Elan. What sets it apart still more distinctly is the ride, which isn’t all that good. The Z1 wears fat tyres – 225/45 VR16s – and their low profiles don’t help the Z1’s case. Absorbency is good on smooth to undulating tarmac, but when the surface is pitted and broken, progress turns jarring, and noisy, too.

The Mazda makes a better fist of roads like this, aided by narrower, taller tyres – they’re 185/60 R14s – besides suspension that is clearly more supple than the Z1’s. It doesn’t impinge. What does is the sheer agility of the thing. Response to the steering is razor sharp. As in a Citroen CX, the steering needs a bit of acclimatising to if the wheel isn’t to be swivelled too far. The effort needed is low, but there the analogy ends, because the resistance in the mechanism doesn’t seem artificial. It’s hardly over-laden with feel, either, but it does feel right.

A major reason for this is that its weighting matches those of the rest of the controls. This is a low-effort machine. Just a dab of the brake slows it noticeably. Crushing the clutch doesn’t take much thigh-thrust. You can pull up the handbrake with a solitary finger. And best of all, you can slide the gearlever about with a single digit, too. It has gloriously short throws that will be familiar only to those who’ve driven a Caterham Seven.

The motor is responsive, too, but it doesn’t turn the Mazda into an earth-burning road-rocket – there simply isn’t the horsepower for that. Nor is there the torque. The baby twin-cam doesn’t really get humming until the crank’s spinning at 4000rpm plus, when in the first three gear ratios at least, there’s noticeable extra thrust. This is accompanied by enthusiastic mechanical noises from up front which, if they aren’t musical, certainly don’t deter you from forays to the 7200rpm limit. The available pull in fourth and fifth is less electric, prompting keen use of that flick-switch shift, and that just heightens the fun of driving it.

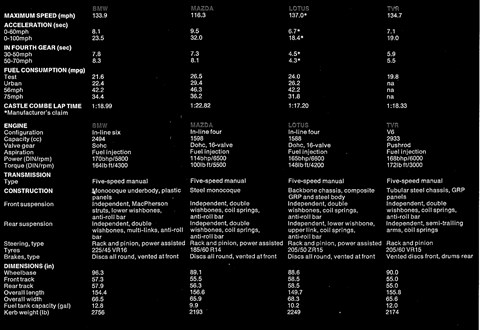

If you’re looking for the pace-setter, though, it’s the Lotus. At one extreme we clocked the Mazda at 9.5sec to 60mph and on to a top speed of 116mph, and at the other comes the Elan. We couldn’t confirm Lotus’s claims, but they’ve been reliable enough in the past, and amount to 6.7sec for the 0-60mph sprint and an all-out speed of 137mph. Between these extremes lie the TVR, which, at the Milibrook proving ground, charged to 60mph in 7.1sec and hit 135mph, and the Z1, which will top 60mph in 8.1sec and 134mph.

The Lotus doesn’t feel blisteringly quick in the first few miles. As you’d expect of small, turbocharged engine, throttle reaction isn’t acid sharp. But it’s respectable, and you’re never left cursing the invention of the blower. Once it’s spinning, acceleration builds very swiftly and it’s easy to keep the momentum going because the power band’s wide. There’s useful effort when the crank is stirring at 2500rpm and the urge isn’t over until the red paint is broached at 7000rpm, It’s an efficient, seamless engine, and sounds it, too. It hums rather than roars it doesn’t even boom, usually a failing of fours. The trouble with the Elan’s engine is that it sounds as if it came from a small, swift and well-mannered saloon, not a sports car. The motor doesn’t goad you.

If you want a car that sounds like a sportster, then the TVR is your machine. It sounds great at idle, invigorating in mid-range and cataclysmic when the V6 is working hard. It may have six cylinders, but this motor sounds as if it came from a Yank V8 NASCAR stocker. The music isn’t a false promise, either. The TVR delivers what none of the others in this quartet can – instant, urgent action when you press the pedal. Better still, it comes no matter what the crank speed. At 1500rpm in fourth you’ve got enough grunt to overtake, though the S isn’t as tractable as it should be, stuttering at low revs in high ratios.

The solution, of course, is to accelerate, which the TVR does with spine-tingling zeal, right to its 6000rpm limit. The curiosity is that the Ford lump sounds smooth right to the end, whereas in the car it came from, grumbles start from as little as 4000rpm. Amazing what some trick manifolding can do. It’s a pity that the Blackpool engineers weren’t let loose on the Z1’s tubing. The six sounds smooth, but not meaty. Strange tingling and tappet noises emanate from the facia, and they rather undermine the creamy delivery were used to from this engine.

For all that it still sounds nicer than either of the fours, especially in the mid-range. And that’s where you need to keep the tacho needle hovering if you want solid go from the six, because it feels distinctly languid low down. Hit 4000rpm, however, and it galvanises, hauling the Z1 ahead with real zeal. But ultimately, this car is short of go. You expect more given its looks, and a hell of a lot more given its £36,925 price.

Compensation, in part at least, arrives via the chassis. The Z1 has grip that feels as if it will never run out, poise and, aboveall, wonderful balance. The steering isn’t as absurdly quick as it is in the Mazda, just intelligently measured, and – produces pleasingly immediate reactions from the BMW, without making it feel nervous. Once in a turn, you can adjust the car’s line without unsettling it, power on or even back off with impunity. If you have to make a correction, it will be small. This holds true on bumpy roads, too, in spite of the Z1’s occasional difficulties in absorbing the onslaught of rocky tarmac.

A problem you’ll experience regularly, however, is tramlining. The Z1 is forever trying to roll off the road’s camber. It’s also re-directed by variations in the road surface. This is a problem that simply doesn’t figure in the Elan. in fact, one of its most impressive qualities is directional stability, a benefit, of course, of front-wheel drive. It’s also the corollary of a fine ride, which becomes more apparent the harder you go. And you can travel tremendously fast cross-country in this car, faster than virtually any other.

That the front wheels do the driving is rarely betrayed. You stumble on clues if you power out of very tight turns, when there’ll be more understeer than you’d get in any of the others, when you accelerate flat-out on wet, bump-riddled roads in low gears —which generates some torque steer — and when you lift-off, mid-bend, which causes the line to tighten.

These foibles rarely figure, mind. You spend vastly more time being impressed and even astonished by this car, than you do being disappointed by it. It handles neutrally 90 percent of the time, flaunting a balance that rivals the Z1’s, swallowing pocks, dips, humps and bumps as if it were some high-speed assault vehicle conceived for NATO forces. Speeds that you’d consider unwise in the other three, even the BMW, are on in this car. That must be one reason why, at low speed, the steering feels a little slow —the Elan doesn’t turn particularly incisively. But if it had ultra-quick steering like the Miata’s, it would be disconcertingly twitchy at the high speeds for which it was built.

There is a dynamic flaw, though, and that’s in the brakes. They don’t lack ultimate stopping power, but in this car the pedal travel was over-long, mushy and short of feel. Production Elans are better, up to the standard of the BMW and TVR brakes, which have a shade more travel than they should but don’t lack much in feel and bite.

The Miata’s brakes are very different, being light and short travel. You must be delicate with them, as indeed you must be with the whole car. Even the most uninterested of drivers can’t fail to notice that this is a very responsive car, so sensitive is the steering and so swift the car to respond. In fact, this rapid response is in part contrived, intended to make the car feel like a sportster even on a drive to the corner shop. Add speed, and the dartiness disappears, which is just as well. But press it hard, and there’s no hiding a well sorted chassis that’s satisfyingly quirk-free. Despite slender tyres, the Miata hangs on really well.

True, there isn’t the power that the rest of the quartet can field, but it’s an impressive achievement nonetheless. If you do get an opposite lock moment, in the wet say, it’s none too easy to correct because that steering is so quick.

It isn’t in the TVR. That’s mostly because the rack is unassisted, and it has to swivel wider, 205/60 rubber. Yet the steering isn’t excessively heavy at a crawl, and it’s very manageable on the move. That wasn’t the TVR’s biggest surprise, though. Plenty of us thought that it would be badly shown up at Castle Combe, where we took the foursome for a workout. It wasn’t.

It was second quickest around the track, after the Elan, and that wasn’t all down to the grunt factor. Grip is superb, even in the rain. In fact it proved very difficult to dislodge the rear end, and that has to be down, in part, to the excellent weight distribution.

The TVR feels very securely planted, on track and road, and even when bumps get the better of springs and dampers it stays faithful to your line. What separates it from the others is a lack of finesse. It doesn’t have the agility of the others, and needs more work to drive hard. But its barely less rewarding. It delivers just the sensations you’d hope for in a sportster.

So that’s what they deliver on the road. it would still be fun if these cars had tin-roofs. When you peel their roofs back, the entertainment factor trebles, The effects of decapitation are much the same in all four. You’re buffeted from behind in them all, but in balmy conditions it doesn’t bother you much. If you like driving topless in winter — and if you’re going to exploit these cars, you’ll have to —you need a good heater.

Easily the best is found in the BMW, which can roast and demist to great effect. The Mazda and Lotus toasters aren’t as powerful, and the Elan’s isn’t very versatile, either, but they suffice. You can get warm in the TVR eventually, and demist the front screen at least, but it’s a struggle, and the battle isn’t made any easier by a fan that roars loudly enough to compete with that V6 burble.

You can defeat the efforts of the Z1’s heater, though, by driving it flat-out with hood down and doors submerged in sills. People probably think you’re mad, but what the hell? This is one of the most exhilarating drives you can have. You wouldn’t want to go far and fast like this, but door down is fine below 50mph. That’s just one of the Z1’s appealing quirks. Others include the wacky seat design, the strange, minimalist, instruments, in which the speedo and tacho are differently sized and styled, the car’s unusual proportions, and the novel cabin trim.

Irritations, apart from the sometimes crashy ride, include excessive noise, from engine, tyres and hood, which provide serious competition for the stereo at 80mph, the almost total absence of storage space, the tiny boot and most obviously of all, left-hand drive. And the Z1 isn’t anywhere near as well made as lesser BMWs. Trim fit is patchy, there are rattles and the car feels less solid than the standard Bavarian motor.

The Lotus is better made, and that’ll be a shock to devotees of the marque. Our pre-production car felt wonderfully robust, was rattle-free and enjoyed good fit and finish. And this was the first Lotus this magazine has ever had on test in which nothing went wrong, or dropped off. Final proof has yet to come, but this feels as if it will be a dependable car.

It’s an easy car to live with, too. The cabin is well planned and convenient, with the exception of the invisible Clock and the nasty instrument markings, the hood is easy to use, as it is in the Z1, which has similar arrangements, the seat are comfortable and almost uncannily supportive and there is actually some storage space and a fair boot. More important, refinement is excellent. Noise from all sources is well muted, including the hood.

The same is true of the Mazda, which is even more painless to live with. It has a hood that’s even easier to collapse — and it can be done from the cabin — visibility is the best of the bunch and everything works well. Finish is good, but not up to other Japanese cars. Panel fit varies a tad, there are weld marks visible in places and, of course, there’s all that low-rent plastic in the cabin. It looks a bit cheap in places, but then it is a cheap car — in America, the country for which it was designed. Fitting a Momo leather wheel, as Mazda does for the UK, will not hide that fact or justify the £14,219 tag we suffer here. They pay £9000 in the United States.

The Mazda’s high price makes the TVR’s £16,645 tag seem terrific value. This is easily boosted by a couple of desirable extras (our car had £1500-worth of hide trim) but there’s nothing essential missing from the base specification. Finish? Well it’s not up to the others, but then you’d expect that. Panel gaps are generous in places, the air scoop on the bonnet is badly finished, bits of the cabin look amateurish and prone to leaks.

But our car felt tremendously solid, its paint finish was superb, and nothing went wrong. Points were lost for the pathetic door mirrors, the high speed din, stupidly positioned gearlever, which is too far back, instruments that are hard to read (and missing a trip-meter) and a tacky steering wheel. But you can forgive it all this, just for that exhaust note.

What should you buy? Any of them. They’re all marvellous. But if you have to choose, then there are two you can live with every day, and two that you can’t. The BMW is just too hard to get in and out of, its cabin too vulnerable to be serious everyday transport. And there’s nowhere to put anything. What damages its case more completely than anything else is its ridiculous price. It might be built at a trickle, it might be a copy of a show car, it might be wonderfully eccentric, but it isn’t worth £37,000. The TVR is borderline as serious transport, too. Again it’s hard to get in and out of, it’s far too noisy for long distances and its ride is jarring for too much of the time. But it’s almost there.

The Lotus and the Mazda you can enjoy on any journey. The only compromise they place on you is the one that all two-seaters present — they don’t have four seats. When they’re as painless to own as this, you can enjoy their lengthy list of attributes all the more. Of the pair, we’d go for the Lotus if the extra money for the £19,850 tag can be found. The edge in all-round ability more than outweighs the extra cost.

But this is being rational, and that’s a foolish approach when you’re dealing with these cars. They are all wonderful, and if you owned any one, you’d feel mighty pleased with it. Now we need more manufacturers to show the guts these have.

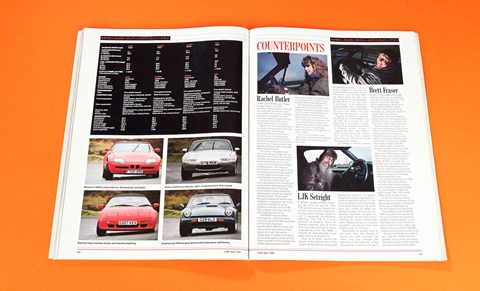

Counterpoints

Rachel Butler

If my legs were just two inches longer, I wouldn’t hesitate in declaring the TVR my favourite. But driving an open two-seater with a pillow wedged between my bottom and seat back because the seat won’t go far enough forward for me to reach the pedals, is not ideal.

Apart from this oversight (and it’s quite a major one, for I’m not an especially abnormally proportioned five-foot-four) I loved this car. It might be the least sophisticated of the four, but for a roadster that’s not such a bad thing. There’s something deeply satisfying about its gutsy down-to-earthiness.

You sit low, the pedals are heavy, the gearchange stiff and the ride hard. Touch the throttle and the car roars forward, And that’s the best bit of all – that noise, It’s a wonderfully throaty, throbbly growl. This really is what sports cars are about. Only not when you’re having to perch on the edge of your seat, toes outstretched, to make it go.

To be fair to the Lotus, my early retirement from the test (on account of carelessly flushing a contact lens down the plug-hole) meant I had to base my impressions on just two laps of Castle Combe. These were enough to establish that it was indeed an impressive car, but it just didn’t satisfy the same primeval instincts as the TVR. That engine could be just any old Japanese 16-valver.

The BMW I found rather intimidating. Left-hand drive and driving on the left-hand side of the road are a bad combination. What’s more, the view out the back was not too good. All in all I felt rather vulnerable. It rattled more than you would expect, and even the slight camber of the outside lane of the motorway sent the Z1 pitching towards the barrier. The sliding doors are a bit of a lark, but £37,000 is too high a price.

The Mazda is quite the opposite. Not only is it the most elegant and the cheapest of the four, it’s also the friendliest. No familiarisation is necessary before you can have fun in this car. It’s slower than the rest, but nevertheless feels nimble and agile, especially through bends, And the cabin is pleasingly bare-essentials, if it does look a little cheap.

If it was my money I was spending, I’d choose the Mazda. But I’d still be hankering after the TVR.

LJK Setright

It is not always true, that you get what you pay for. The TVR would have you fooled, for a start. ‘Look at me’ it beckons, flexing some muscles. ‘Listen to me!’ it demands, incontinently belching. The TVR is a lout, ignorant of humane ideals, of human anatomy, and of much that has been learned in motor engineering since the 1960s. I should be embarrassed to be seen near it, let alone in it.

Only as its driver would I be aware of the deficiencies of the Lotus. Its front-wheel drive gives me debased steering, its instruments printed in invisible red on inscrutable black give me no information, and its high steering wheel gives me the suspicion that the car was designed by GM. Worst of all, the Lotus is non-linear in its behaviour, unpredictable and unpardonably erratic in every translation of cause into effect. The car goes fast, but driving it is nasty.

Despite its flyblown ugliness, the Mazda is a little sweetie, not as little as it should be, but behaving to a nicety in every-thing it does. Maybe a little short of braking power, though I suspect the tyres were responsible, it never gives the impression of having more engine power than it can handle. Quite the opposite, indeed.

The BMW is simply superb. Marvellous balance in every-thing from chassis dynamics to control-matching proves it the work of masters, and if it profited from better tyres than the other cars, full marks to BMW for specifying them. Praise also for sensible seat-trim suitable for wet weather, for the best hood-latching, the most comfortable open-topped cockpit, and utterly delightful sensations from the engine and all controls.

Admittedly its quality costs a lot more than the Mazda (I would not even consider the other two), but consider the obverse of my opening: unless you pay for it, you do not get it.

Brett Fraser

I can’t pick a winner. For starters, they’re all convertibles, so that’s an instant point in their favour in my book. Besides which, they’re all so good, and all of them in different ways.

The Z1 is for posing. It’s so outrageous, a designer label on wheels. But it is certainly impractical. The boot is about big enough for a briefcase and a packet of crisps, so outings in it should be within reach of home.

But provided you’ve got no particular place to go, the Z1 is a smile a minute. Drop those fancy doors and a new motoring experience opens up. You can see the road right there by your side, reach out and pull weeds from grass verges. And this while perched on one of the best-balanced chassis around.

The Elan I’d save for those days when I felt like driving fast. Really fast. Over roads I know well, winding, narrow, Norfolk lanes, the Elan is by far the swiftest car I’ve ever driven. The quality, the suppleness, of its chassis, means you can brake later on a bumpy approach to a corner than you can in more stiffly suspended cars.

If only it sounded like the TVR. The Elan has a wonderfully refined and powerful engine, untroubled by excessive turbo-lag, but it doesn’t make the right noises. The TVR, on the other hand, makes music. It’s the car I’d take on tour. When you’re in the mood, it has the power and grip to entertain. When you in sight-seeing, the S is happy to lollop along.

For everyday use the Miata (MX-5 sounds too impersonal for a car of such character) is perfect. It looks superb, is just the right size to be nimble on back road or in city traffic and feels as if it would last 100,000 miles without using a drop of oil.

What all of these cars offer is fun-lots of it. At the end of a journey, any journey, you step out grinning, and start making excuses for going out again.

Read more classic CAR features