► The ultimate Porsche 911 group test

► 2.7 RS, 959, 964 RS, 993, 997 GT3…

► Key milestone models from 50 years

How do you represent 50 years of the Porsche 911 in one road test? Should you be completist? Not when the previous generation alone stretched to over 20 variants. Trawling through every offshoot of every generation would be like locking yourself in a room with an elderly relative and a slide projector. But do you choose the base models? The sporting thoroughbreds? The biggest technical leaps? It’s an endeavour fraught with hand-wringing and endless possibilities and the fear that, come the end of it all, we’ll get a couple of emails complaining that we’ve left something out and that the whole shebang really must be better come 2023.

So we hope that the cars we’ve shepherded to Brands Hatch paint a succinct picture of the journey undertaken by the world’s most important sports car: the guiding hand of motorsport, the ever-expanding breadth of the brief, the purity of the basic cars, the heady thrill of the hardcore variants, and the process of continual evolution punctuated by giant, sporadic leaps.

There’s a car from each generation save for the current 911. And what better place for us to start than the grandaddy of the most recently launched 911 GT3, the iconic 2.7 Carrera RS of 1972-’73?

With almost ten years of honing under its belt, the Carrera RS represents the zenith of first-generation 911 development and the moment that ‘Carrera’ (a reference to Porsche’s class win on the Carrera Panamericana) and ‘RS’ (for Rennsport, motorsport in German) first appeared on a 911 bootlid.

It started when Porsche began developing the 911 for Group 4 racing once the all-conquering 917 prototypes were outlawed from the World Sportscar Championship. The pokiest S model was deemed too heavy and its 2.4 litres too lazy, so the RS was bored to 2687cc for 207bhp and 188lb ft, up on the S’s 187bhp and 159lb ft. There was also thinner-gauge steel for some of the panels and thinner glass too, along with a pared-back interior, strengthened suspension mounts and gas-filled Bilstein dampers in place of the S’s Konis. The gearbox and brakes remained standard.

Click the handle, gently swing out the light driver’s door and you lower yourself onto a bucket seat with a fabric covering that looks much like a throw you’d put over a tatty sofa. The seatbacks are fixed and very upright, the base firm and offering precious little under-thigh support. You grip a broad, thin, four-spoke rim, one that frames a rev counter that’s redlined at 7200rpm – high today, nevermind in the early 1970s! It’s just-and-so larger than the speedo, a little nod to what takes priority here.

Turn the key and the engine spins freely and breathily, the revs falling faster than Felix Baumgartner every time you take your foot off the pedal. On the road there’s a real thrill – more so than the sometimes more lethargic newer models – in winding that rev counter right round the dial, the RS still feeling fleet and gunning for the redline with the hyperactivity of Scrappy-Doo shadow-boxing a mystery villain. It feels counter-intuitive to short-shift in this car.

The steering is light and jiggles your hands like a Thunderbirds puppet, and you steer it delicately, flowing down the road with little nudges back and forth, something the excellent ride on those plump sidewalls complements – it means the nudges never escalate into tugs when you encounter ruts or more pronounced cambers.

You need to be pretty physical with the gearshift, though, taking two distinct bites, and it’s perversely hard to heel and toe on these idiosyncratically set-up pedals, let alone use the stoppers to avoid an accident, but it’s impossible not to long for a 2.7 RS once you’ve driven one.

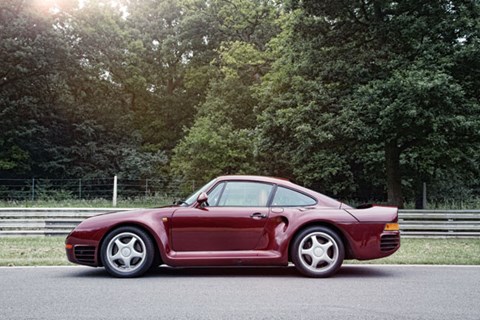

When the second-generation 911 arrived in 1974, the lessons learned from the RS had fed into its development, but that car – covered in our buying guide, page 80 – soldiered on until 1989 and was really a continual evolution of the original. Instead we’ve picked the 959 as the key milestone in the 1980s 911 story. I know, I know, it’s not a 911 proper, but bear with me here; we need a little context.

By the early 1980s the 911 was close to being towed over the border by its front-engined siblings and dropped at a euthanasia clinic with a note around its neck. Luckily for us, new CEO Peter Schutz had no intention of administering a lethal dose, and engineering boss Helmuth Bott longed to build an ultra-911 for Group B competition. The result was the 959, a car most closely connected to the first 911 Turbo of 1975, but radically different too. It’s a car that both takes from the 911 – the glasshouse, the rear-mounted flat six, the interior layout – and gives to it, styling touches and technical innovations filtering into the 911’s genes.

This balancing of past and future is ever-present: the C-pillar is clearly 911-derived, but the little line below the paintwork demarks a composite roof from a steel body. 911 fans might not notice that, but they will double-take when they open the bonnet: you’ll struggle to get a pair of slip-ons in there, a by-product of the four-wheel-drive system’s packaging – today’s Carrera 4 models have whittled that space penalty down to just 10 litres.

Open the treasure-trove-like rear deck and you’re greeted by a 2.85-litre twin-turbo flat-six with its air-cooled cylinders and water-cooled heads. It takes 444bhp to the road via a computer-controlled four-wheel-drive system, and stops you with four super-sized – at the time – disc brakes, ABS watching their backs.

If the 959’s body has echoes of 911, the interior positively screams it. Yes, it’s luxurious for the time and there are what must have seemed like space-age dials to tweak your four-wheel-drive system and firm up the dampers and raise or lower the ride height. But it’s still very much ’80s-era 911 –vertical dash, upright windscreen, scattergun buttons, floor-hinged pedals – and it still sounds like a 911 when you fire it up, chuntering and chattering and rumbling quite rowdily in an endearing kind of way.

Like today’s 911 Turbo, the 959 gets twin sequential turbos, and the example we’ve sourced has the factory Sport-spec upgraded blowers, taking it to 550bhp, perhaps more. Yes, a lot. Even today. It pulls from low down with real smoothness, then you feel the first turbo ignite at 3200rpm and you start to get a proper hurry on. Quick car, you think. Then you hit a pretty late 5500rpm and that second turbo jumps to attention and things go berserk, propelling you to 6500rpm like a firework up a drainpipe. Yet this is no Ferrari F40-style animal: the four-wheel drive offers dependable traction and the steering and gearshift are light and user-friendly too. You’d happily daily-drive a 959.

In May 1984, CAR predicted the 959’s ‘myriad design refinements will filter through quite surely to the rest of the 911s, to refine them further… it probably extends the life of the 911 for at least ten years’. Well, we did say ‘at least’.

One glance at a 964-era 911 from 1989 suggests it had gone for a sulk and refused to grow up when introduced to its new, cleverer sibling. Yet it sucked up the 959’s influence, and its powertrain and suspension and brakes were all new. The danger of hiding its light under a bushel wasn’t lost on Porsche, and as if to stress the technological transfer from 959, it launched the 964 with four-wheel drive first, introducing the Carrera 2 a year later.

This was the step-change that brought the 911 up-to-date with a Tiptronic auto gearbox, ABS and power steering and more creature comforts than ever before. The car we’ve chosen, though, shuns all that: the 964 RS, spiritual successor to the 2.7 RS.

It’s a beautiful looking car, the only RS to feature a rear spoiler that extends at speed, keeping the kerbside lines as pared back and simplistic as the interior. Not that it’s a hardship to sit in a 964. Slide past the firm outer edges of the fixed-back bucket seat and you sink – noticeably canted back – into a deeply padded, leather-trimmed base, the aggressive bolsters preventing you from sliding around on the slippery trim. The floor-hinged pedals are, as ever, twisted towards the transmission tunnel, but the go-kart seating position and small diameter three-spoke wheel – still non-adjustable – mean that kneecaps attached to longer legs are less likely to get in the way as you brake and change gear and steer.

The RS is not a fast car, feeling surprisingly leisurely at low rpms and never really pulling with the spine-tingling vim that you might expect, but it sounds fantastic and handles so sweetly that you stop worrying about outright pace and start focussing on carrying speed, on listening to what the chassis is telling you in the least convoluted terms.

You’ll read that the 964 was criticised at launch for being too firm, but this car feels perfectly acceptable to me, a firmish ride, yes, but one still offering enough compliance to work on a British B-road. It’s poised and adjustable too, never nervy, and all the while you’re pedalling it along, the nose bobbing about gently and darting left and right, instantly dancing to your tune. I love it.

The thing is, the 964 RS is special as much for what it represents as how it drives – it’s the 911 at a crossroads, the classic lines of 30 years before still very much in evidence, the technology available to its siblings overlooked in favour of an elemental rawness. Think of it as one final celebration of the past before progress marched in.

And progress was coming: the fourth-generation 911, the 993, bowed in 1993 and 80% of it was new, including an all-new, more muscular, more rakish body designed by Brit Tony Hatter, while the 964’s semi-trailing arm rear suspension made way for a multi-link set-up derived from the stillborn four-door 911 project. Bar the is it/isn’t it 959, this was the 911’s biggest leap in 30 years, Porsche investing heavily in its halo car, soon to be its only car. Which is why we’ve plumped for the basic Carrera, to see this pivotal 911 wearing the clothes it first met the world in.

Just like the 959, the 993 feels surprisingly familiar inside considering the progress elsewhere: same upright dash with a non-adjustable steering wheel pushed up against it and hiding the heater controls, same upright windscreen with its skinny A-pillars, same old-fashioned-quarter windows and floor-hinged pedals, same kind of stubby little gearlever positioned on the deck.

With this car’s standard seats – slippery leather, low on lateral support – you sit higher than in the 964 RS’s low-slung buckets, and the airbagged steering wheel is larger, so I actually have a bit of an effort getting comfortable, knees threatening to snag the steering wheel, left foot constantly dragging against the under-dash gubbins as I feed the long-travel, weighty clutch in and out.

But I’m glad for the progress beneath the skin when I head out on the road in a deluge: it’s a very well-mannered machine, with lots of grip and traction and a very forgiving ride, but it still retains a sense of delicacy and fun despite reaching middle age. There’s not the feel I was expecting through the steering, though – bar the 959, the first of our 911s to get power assistance – and the 268bhp performanc is a little lackadaisical, waking up at 3800rpm but never delivering the intensity you’d get from its contemporary over in Munich, the similarly powerful E36 M3. But on track the 993 is still satisfying, the roll on turn-in translating to easy oversteer if you’re that way inclined – or just a bit late on the brakes. And the 993 will have the last laugh on those M3s: its chassis is sharper and its fixed-calipers and cross-drilled discs are far meatier than its rival’s weedy stoppers.

If you wanted to really humiliate the BMWs? Well, there was always the Turbo, the clearest sign yet that the 959 was fertile, a 911 with four-wheel drive and twin blowers pushing it to a heady 402bhp.

Glancing at the spec of the 996-generation Turbo that replaced it in 2000, you’d be forgiven for thinking Porsche had slipped back into glacial evolution: four-wheel drive, 3.6-litre flat six, negligible power hike. But the 996-generation 911 in general was another, even bigger shake-up, and one that came just four years after the launch of the 993.

Porsche needed it. After the lean late 1980s and early ’90s, new CEO Wendelin Wiedeking had arrived on the scene and took to producing a new 911 with a logic not before seen. You can understand why he upset people: the fried-egg headlamps, the pooled genes with the Boxster, the water-cooled engine – the latter causing as much consternation as electric power steering does today. But this 911 was cheaper to produce and stiffer, lighter and safer too, and anyway, this wasn’t all about the hardcore fans: this was about getting the non-hardcore to buy Porsches, about Porsche surviving and turning a healthy profit. It worked: by the time the 996 went off-sale, Porsche was the world’s most profitable car maker per unit, the 996 its most successful model ever.

Step inside a 996 and there’s an instant, immediately obvious break with the past: the windscreen is far more heavily raked than before, the dated quarter windows are gone, and the dash – logically laid out but seemingly attired in a fat-suit – is all new. Trundle about and there’s another step-change: this feels like a normal car to drive, in large part down to the more adjustable driving position, the more conventionally arranged pedals and the fluid, easy-going control weights.

It’s perhaps testament to this Turbo’s user-friendliness that it wins today’s high-miler trophy at a healthy 110,000, and perhaps also why it feels a little sloppy and brittle. Yet there’s no doubting it’s underlying talents: when the power kicks in at 2800rpm, it fast-forwards you round the dial to 6000rpm in one even swoop, not the pronounced two-step kick of the 959. It’s a different sensation to the faster naturally aspirated cars, the naughty tingle of excitement that comes with winding those motors out superseded by the funfair woop of a motor suddenly picking up speed despite your fixed throttle position.

It’s the first time today that it feels harder to explore this car’s limits on the road, but on the track its abilities come into focus. Drive the 996 Turbo just a little below the limit and instead of feeling the rear soaking up all the power, you’ll feel an eerie pull from the front that drags you to the next corner as if there’s a giant magnet at its apex. But go really hard and accelerate early and that rear end starts to come back into play, hunkering down and then, as the turbos ignite, slipping ever-so-slightly sideways, the rear tyres fizzing as the boost roars loudly behind you. That’s the more satisfying way to drive a Turbo. It lacks low-down punch, though, and while the initial response to the throttle is sharp, there’s an underlying sogginess that detracts a little from your dialogue.

Which is why, for some, only natural aspiration will do. Want to induct the clueless? Strap them in the passenger seat and give the outgoing GT3’s 3.8-litre flat-six all you’ve got. Then they’ll understand. The GT3 is one of the hardcore versions of the 997-era 911. It’s the modern-day successor to the 2.7 RS and the litmus test for the new 991 GT3. It’s got a lot to live up to: in January 2007, CAR billed the 997 GT3 as ‘the greatest 911’.

This engine has heritage, an evolution of the iconic Mezger flat-six which, among other feats, took Porsche’s 911 GT1 to victory at Le Mans 1998 and starred in previous-generation Turbos, GT3s and GT3 RSs.

At idle it chunters and pulses and you know it means business. You look around you and everything means business too: the cage that criss-crosses the rear screen like a skull and crossbones, the Alcantara-trimmed steering wheel and gearknob, the central rev counter that promises action until 8200rpm.

At low speeds it’s flexible and willing and perfectly quick enough, but there’s a little step at 4000rpm after which it really comes on cam, intensifying a bassy mechanical howl that becomes progressively more demented the longer you keep your foot in. It’s easy to be complacent about the 429bhp and 317lb ft outputs these days, because they’re easily beaten on paper. But on road or track this is sensational performance; you never, ever wish for more.

The GT3 has a mechanical sound and a mechanical feel too: the gearshift is very physical – I like the toil, but no doubt it’ll seem cumbersome to some – and the steering is meatily weighted and streams high-definition detail. It’s the benchmark that the latest car’s electric rack can’t live up to.

In the newest generation, Porsche has lengthened the 911’s wheelbase and really tamed the unweighted front end’s tendency to understeer, but some damp laps at Brands amplify the old car’s delicate balance, the tendency for the nose to push if you get on the power too early and the way you can cancel that out by backing off the throttle and teasing out the fat rear end that comes slowly at first, then swings quickly, the notorious Michelin Cups – more of a liability around water than Whitney Houston – hooking up and smearing two black lines down the Tarmac.

If it’s tricky on the limit, the GT3 is magic just below it with its effervescent front-end response, massive traction and it’s immediate sir-yes-sir response to throttle orders. You’d expect nothing less from such a track-focussed machine, but there’s something else less expected: it’s great on the road and very usable too. There’s nothing else at this end of the market that combines such track-pure thrills with such daily-driver versatility.

It’s why, at the end of our shoot, with six 911s standing before us, I take the keys to the GT3. It’s a car that lifts your spirits in a way that a hunk of metal and four tyres really shouldn’t, and it’s some testament to 50 years of evolution that it stands as the best car here.

Words: Ben Barry Photography: John Wycherley

This feature first appeared in the August 2013 edition of CAR magazine

Thanks to Nigel Mitchell (2.7 RS), Club GT (996 Turbo), www.171959.com (959 and 964), and to Richard Tipper at Perfection Valet (@perfectionvalet)