► Retracing the Orient-Express in a Rolls-Royce

► 2500 miles in a Phantom across lost empires

► Paris to Istanbul in our CAR+ archive adventure

The type of journey the first GT cars were made for: 2500 miles on the route of the Orient-Express. Lost empires, shell-shocked cities, and a Rolls-Royce Phantom

The Hungarian border guards wave us through with one last disbelieving look, and we officially enter Eastern Europe to a fanfare of utter silence. Ahead of us an arrow-straight highway stretches off into the distance, just like the ones we’ve already wrung out across France, Germany and Austria – only this time there’s an unsettling difference: it’s empty. Absolutely desolate, tumbleweed blowing down the centre lane, like a ghost road to nowhere.

What makes it worse is that there’s a traffic jam on the other side of the central reservation, an immense queue of cars, all trying to get out. The line is so long and so static that people are standing in the road, pushing their battered East European hatchbacks to save petrol. It looks like some post-apocalyptic panic, like everyone’s escaping from a volcano or a nuclear explosion, or a rampant virus that’s leaked out of a Soviet lab. They stare at us and we stare back as we swoosh past. It all adds up to the uneasy feeling that we’re heading Completely The Wrong Way.

It’s good to get out of your comfort zone every once in a while, and as we speed across Hungary our comfort zone recedes into the depths of the rear-view mirror. But getting out of your comfort zone doesn’t mean you can’t travel in absolute comfort. That’s how the Orient-Express was born. First run in 1883, the Orient-Express was a steam train of luxury sleeper and restaurant cars that ran east from Paris to the exotic gateway of Asia, Constantinople. By the turn of the century it became the perfect way for the wealthy, aristocratic and powerful to reach distant lands while sipping gin and tonic.

After the First World War, the Orient-Express was re-routed via Venice, Belgrade and Sophia (to avoid Germany), and in 1921 you could get from Paris to Istanbul (as Constantinople had now become) in just 56 hours. This was the heyday of the Orient-Express, a time of elegant evening dress in the restaurant car, of spies and intrigue, of Agatha Christie.

The Orient-Express literally ran out of steam after the Second World War, and declined to almost nothing until 1977, when the old coaches and restaurant cars were finally bought up, restored and revived. Now the train represents luxury on wheels once again. Not only that – every year it still makes one epic trip from Paris to Istanbul, via the original route. It costs about four grand, one way.

But the train isn’t the only way to cross continents in the 21st century. Nowadays you can cross Europe by car or bus, or you can hide on the top of a lorry, depending on the state of your passport. But there’s only one alternative that offers anything like the romance and elegance of the Orient-Express. Like the train, Rolls-Royce also ran out of steam before being revived (by the Germans, ironically) in the form of the magnificent Phantom – £270,000 worth of V12, leather-bound, land-of-hope-and-glory mobile comfort zone, complete with lamb’s wool rugs and electrically operated rear ‘suicide’ doors.There’s only one car in the world that can do the Paris to Istanbul route of the Orient-Express any kind of justice, and this is it. And I have the keys. So what are we waiting for?

Wafting along a smooth French autoroute, the Rolls-Royce Phantom is so quiet you can hear the whistling of fans in the air vents, and the faint tremble of a speaker’s inner cone in the door. It’s a bit unnerving, like you’re about to sink under the soporific spell of a general anaesthetic.

There aren’t many buttons on the dashboard to keep you occupied either – the Phantom uses a BMW 7-series switch pack, but Rolls-Royce chose to keep it discreet and dispense with the power station control panel that most luxury cars favour nowadays. So, to keep ourselves awake across hundreds of miles of well tended EU farmland, we just drive really, really fast instead. At around 100mph, the wind noise does start to encroach a little, and by 120mph it’s almost loud enough to wake you up. You start to feel the aerodynamic effect of the huge frontal area now, which is hardly surprising given that the Phantom is an extremely tall, extremely upright car. From here you look down disdainfully on BMW X5s.

The view ahead is pure classic car – slightly finned wheel arches mark the edges of the big, flat bonnet, with a chrome strip that leads your eye down the centre to the Spirit of Ecstasy. With 6.75 litres of V12 at its disposal, the Phantom hasn’t finished yet, and it exhibits amazing stability as the 453bhp pulls towards its top speed of 149mph.

Stay alert, though – when someone pulls out half a mile ahead, you’d better be on the brake pedal fast because this car carries massive momentum, and while the brakes are ace, you sense an accident in the Phantom would be messy, like a Sherman tank through a supermarket.

France and Germany are very big, but we’ve taken the decision to dispatch both in a single day, just as the Orient-Express does. With a 100-litre tank and 400 miles between fills (at just over 17mpg) it’s an easy cruise, and stupefyingly comfortable – especially if you sit in the back. Which I do. To pass the time I memorise some handy phrases from our phrase book: ‘Beyin tava istememistim’ (I didn’t order the fried brain); ‘Ima umrial v baseina’ (there’s a dead person in my swimming pool); and ‘Cineva mi-a furat Rolls-Royce-ul’ (somebody has stolen my Rolls-Royce).

We arrive in Salzburg, home of Mozart and The Sound of Music, and after 800 fast miles the car feels like it’s freewheeling as we roll silently over the dark waters of the Salzach river, and into the narrow streets of the old town. And so begins a phenomenon that recurs throughout our time with the Rolls: stop for one minute on the street and the car is encircled by amazed onlookers. Tourists stop taking photos of Maria von Trapp’s birthplace and start taking photos of the car instead. We find a modern multi-storey, and park on an empty floor. It doesn’t fit in a normal space, so we leave it lengthways.

We wake to the same view that passengers of the Orient-Express enjoy on their first morning: the green foothills of the eastern Alps; but while they’re served coffee and pastries in bed, we’re up and off to enjoy the mountain roads. If the car’s size is an issue in a multi-storey car park, that’s nothing compared to a twisting Alpine road. It actually handles pretty well, but the long wheelbase does hamper your racing line through tight hairpins. Best to take it wide and slow.

The other thing you find is that the Phantom just runs away down hills. The six-speed gearbox has so much torque at its disposal (531lb ft to be exact) it usually sets off in second, but after spending half my time on the brakes, I discover the ‘L’ button on the steering wheel. This engages ‘low’ – also known as ‘first’ – to induce a bit of engine braking. It also induces a 0-60mph time of 5.7 seconds, which comes in handy later.

When the Alps finally peter out we follow the mighty Danube past Vienna, and push on towards Eastern Europe across the Great Hungarian plain. It’s funny – with all its borders and kingdoms and languages, we don’t see the European continent in the same way as North America, but travelling across these farmlands feels like crossing the prairies of the Midwest.

Hungary joined the European Union in May 2004 – so we’re all friends now – and the border guards wave us through cheerfully; but you can tell that this country hasn’t kept up with the West. Unfortunately Hungary backed the losers in all the major conflicts of the 20th century, and after the Hungarian uprising in 1956 it came under Soviet control. So while the scenery stays the same, suddenly there are horses and carts on the roads, and every time you drive into a town the first thing you meet is a decaying factory. It’s hard to buy postcards in places like Gyor, Komarom and Tatabanya.

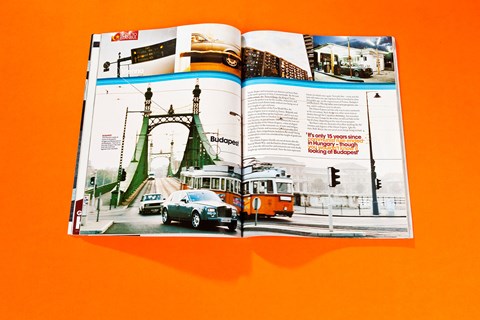

But Budapest is different; 1450 miles from London, it is the first overnight stop for the Orient-Express, and it’s a beautiful city, in its own dilapidated way. Austere 1950s trams rattle past fabulously grand buildings of the Austro-Hungarian empire. It’s only 15 years since communist rule ended in Hungary, but you wouldn’t know it from Budapest – people know how to earn and spend money here, and while the Rolls-Royce still stops people in their tracks, its imperious presence doesn’t look out of place.

Soon we’re at the border with Romania. After the usual border control procedures – let the guards sit in the driver’s seat, show them the back doors, pop the bonnet, tell them the Phantom costs 400,000 euros – we continue east. Romania is big, but you sense the bank vaults have been empty for a long time. For starters, everyone drives a Dacia – not the new Logan, but the Renault 12 that was built under licence here from 1969 until 1996. Under communism, buyers waited two years for the privilege of owning one of these skinny little saloons.

Alongside the Dacias on the road are ancient wooden carts and tired horses that look even more dangerous than in Hungary, and you see people living on the roadside in genuine third world, grimly African poverty. First we meet the old biddy selling water melons, living in an Eeyore hut made out of sticks and plastic bags, with a mongrel dog that eats nothing but water melon; then there is the honey doctor, who sells different flavours of honey labelled as medicines for things like ‘vitality’, ‘stress’ and ‘headaches’.

These people live so far off the economic scale they hardly even notice the car. The gypsies are the same; Romania is known as ‘the gypsy country’ – a big proportion of the world’s ‘Romany travellers’ live here, though the similarity in name is a coincidence (Romania is called Romania because it was once a Roman colony). Anyway, with their dark complexions, red embroidered clothes and floppy felt hats, they make Romania look like a faded photograph in a 30-year-old copy of National Geographic.

You can imagine the effect the Rolls-Royce Phantom has when it strolls into town. It’s like driving a circus big top. We stop the night in Sibiu in the heart of Romania, an idyllic 17th-century market town that’s so unspoilt it’s like a costume drama movie set. For a long time Sibiu was considered the absolute edge of ‘Western’ civilisation, and European postal services reached here and no further.

We arrive at 10pm, and pull up outside the hotel in the centre of town to discover we’re in the middle of a wedding party. Pandemonium ensues: young guests stagger out in shock, taking turns in the driver’s seat as flashes go off everywhere. ‘It’s just like my Dacia!’ one of them announces optimistically. The groom comes out, and is so impressed he goes back in to grab his reluctant bride, who duly stands by the car for photos.

We check in, and learn that the hotel car park is round the corner; I find I have three excited and slightly drunk passengers in the Phantom for the two-minute trip. ‘This car has no engine!’ they shout from the back, amazed, as the car glides silently through the dark streets.

The whole north west of Romania is known by another, more romantic name, Transylvania – and you can see how this region provoked so many dark mysteries in the past. The next morning, as we head into the Carpathian mountains, the dense, eerie woods and hidden valleys add to a feeling of strange uneasiness. Or maybe it’s the tripe soup repeating on me.

The valley we follow, up above the tree line and into the grey clouds, is as impressive as any Alpine pass – a soaring, twisting, knotted ribbon of tarmac, with the added thrill of crumbling walls, bad drainage and no railings on the lofty edges. The final pass at the summit takes us through a long, pitch black tunnel, with piles of rubble picked out by the headlights in the gloom, marking where the roof has caved in. The gloom continues in Bucharest, the town Vlad the Impaler called home sweet home, and once known as the Paris of the East. It still has an Arc de Triomphe but Bucharest is now a strangely soulless city. Blame it on the detested communist leader Nicolae Ceausescu, who had much of the centre knocked down and rebuilt in epic, megalomaniac style, before the mob finally cashed in his chips in 1989.

You can imagine, after all this, what we’re expecting of Bulgaria – goat herders in the road, people living in caves, diseased mules dragging medieval carts over stone tracks. Imagine our surprise, then, when we cross the border over the Danube to find a row of TV cameras waiting for us. Word has got out that the first Rolls-Royce Phantom in Bulgaria is arriving, and the national press turns up. If you’d watched the Bulgarian News at Ten that night, you’d have seen bombs in Iraq, hurricanes in Florida, and a mumbling Brit trying to think of the Bulgarian word for ‘fully variable valve lift control’.

We’re wrong about Bulgaria. Like Hungary and Romania, it was absorbed into the Soviet sphere after the war, and with its Cyrillic alphabet and all the Volgas and Moskvitches on the roads, it’s the most Russian-looking place we’ve been to yet. Since its own quiet revolution in 1990, though, Bulgaria has been thriving. The shops and bars are busy, and BMWs and Mercs mix it with the Ladas. In one town there’s even a late-1990s Ford Mustang convertible, obviously the local big shot’s. We line up beside it at a set of traffic lights, and I sense the driver eyeing up this gargantuan imposter on his patch. I blip the throttle, making the Phantom rock on its suspension like a ’60s musclecar, and as I glance over, press the L button on the steering wheel. I narrow my eyes. He stares back down the road. Then, as the lights flick green, I mash that Rolls pedal so deeply into the floor it squashes pile of the lamb’s wool rug. Our heads are momentarily thrown back as the limo squats on take off. The Mustang simply vanishes.

The triumphant smile falls away when it dawns on me he’s probably a ruthless East European arms dealer with a sideline in prostitution and drugs. And I’ve just embarrassed him in front of his girlfriend. I spend the next five miles anxiously checking the rear view mirror.

I needn’t have worried – the Rolls-Royce is The Daddy, and the driver of the Mustang was probably more wary than me. Every time we ask directions in Bulgaria, I see the farmers and shopkeepers grovel and bow to hopelessly lost photographer Gus Gregory and his upside down map. They seem to think he’s the president or something. No other car in the world has a presence quite as magisterial as this one.

Not only that, people know what it is too. Drive through a remote village and the locals almost cross themselves with awe, and you hear them murmuring under their breath ‘Rolls-Royce, Rolls-Royce’ like a religious chant. After more than 2000 miles of driving, we reach the Turkish border for our last leg, but not without one final rendezvous. The timing of our trip isn’t arbitrary – three days after our departure from London, the Orient-Express set off from Paris on its annual trip to Istanbul, and has been playing catch-up ever since. We’ve calculated that the train will cross from Bulgaria into Turkey on the Thracian plain tomorrow morning, and we’re determined to drive alongside it. Finding the track is easy; finding a place where the road and track run side by side proves more challenging. We end up driving down dirt tracks at midnight. They get more and more rutted until they disappear into dark fields of bare earth, and there’s a moment when I find myself off-roading a £270,000 Rolls-Royce, doing a three point turn in the blackness, in afield, all signs of civilisation beyond the horizon. Funny how you end up in these situations, isn’t it? But by now the awe of driving the Phantom is gone, and it feels just like a strong, confident saloon that was built for adventures like this. Remember, Lawrence of Arabia drove a Rolls-Royce in the desert (come to think of it, he used it to blow up Turkish railways tracks).

So the next morning we’re on our stretch of road, and after a few false starts, we hear a train in the distance, and as it rounds the bend we see the glossy blue coaches and white roof of the Orient-Express, the gold lettering glinting magnificently in the sun. We accelerate hard and drive alongside the train for a few hundred yards, while breakfasting passengers look out in amazement; and when the driver blows his horns, to my ears he’s honouring this special bond between car and train, these two exotic continental travellers nearing their destination!

Then I realise he thinks I’m going to run the next crossing like the locals do, and as I slam on the brakes at the barrier, the train slopes off into the hazy distance. Next stop, Istanbul.

Istanbul, Constantinople – city of the rich Byzantine and Ottoman Empires, jewel of the Christian and Islamic faiths, home to some of the most beautiful and famous mosques in the world – is a real dump when you approach it from the west. They reckon upwards of 12 million people live here, and to get to the old city on the tip of the peninsula, first you have to drive through miles of prefabbed concrete slums and blocks of flats.

But it’s worth it. When we arrive in the old town, the Rolls-Royce will barely squeeze through the labyrinth of streets, and traders and shoppers press against the car so tightly the wing mirrors keep flipping back. Every eye in the street is on us as we crawl through, the air thick with the heat and smells and sounds of the East, bustling and chaotic, until we reach the elegant Sirkeci station, purpose built in 1890 to receive the Orient-Express. As we arrive we hear the last notes of the traditional Turkish music that’s playing out a welcome for the train, and with special permission we drive the Phantom straight onto the platform and park it beside the gleaming train.

We’re basking in the moment – a moment that after 2500 miles of motorways, multi-storey car parks, fast food chains and mobile phones shows that the romance of travel is not dead yet.

Postscript: The morning after our arrival in Istanbul we visit the ancient Cagaloglu Turkish baths, where Sultan Mahmut I enjoyed an 18th century scrub up. Nowadays it’s used by everyone from tourists to local taxi drivers.

Once you’ve changed into a cotton towel you’re shown into a domed room made entirely from pale grey marble and filled with steam rising through shafts of brilliant sunlight. The city seems a millions miles away, and the only sounds you hear are the drips of condensation falling from high above.

I sweat on a raised slab of smooth, hot marble for 20 minutes, before a hairy Turkish man comes in and gives me a massage so merciless and violent it almost beats the very life force out of me. He squeezes, punches and slaps me with his mighty hands, grabs my limp body and flips me over so I’m looking straight up at his huge moustache. Then he folds my arms over my ribcage and with an action like he’s packing the last item into an overstuffed suitcase, he jams down hard on my wrists. My spine flattens against the marble slab beneath me, and emits a crack so loud it ricochets around the domed walls like a gunshot. His moustache twitches.

Can I get back in my Rolls-Royce now, please?