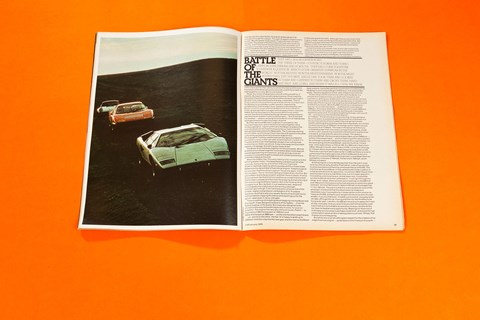

The noise pulled faces to every window as the cars went through the villages. The sight dragged crowds to every square. Mouths gaped. Eyes stared. Fingers pointed. Children squealed. The people of the Pennines had never seen anything like this, and if they found it hard to believe then so did we, for it had taken more than a year for the dream to be realised and there were times when I for one had feared it never would. But there I was – there we all were – with the wheels solid in our hands and the throttles firm beneath our feet and the noise loud in our ears as we whipped along the roads to the moors, roads chosen with meticulous care for their ability to extract the best and worst from each of the three cars and so provide us with the answer we had sought for so long. Which one is best?

Three, four times it had almost come off in the preceding 12 months. But each time something went wrong. Once it was the Countach that left the country hours before we were due to get it. Another time it was the Porsche that was unavailable. Then a truck crashed in front of the Ferrari and the mechanic preparing it for delivery to us next day couldn’t avoid it; it was hollow compensation that he wasn’t hurt. Someone else blew the next Boxer’s clutch in an effort to determine its acceleration times, so we had to live again with disappointment. Summer faded, the five Countachs in the country were firmly in their owner’s hands and it looked as though we were going to take the Ferrari and Turbo to Switzerland – and to hell with the weather – where Lamborghini boss Rene Leimer had said we were welcome to his own Countach, anytime.

But then we found William Laughran in Lancashire. His Countach was ours, and in the end it all came together like a military operation. I went north first in the Boxer and about the time I booked into the hotel that was to be our base Leonard Setright boarded a plane for Newcastle. The Turbo was waiting for him there, and he drove it from one side of England to the other sufficiently quickly to arrive in time for a late dinner.

Photographer Franklyn and third driver Sturgess stumbled in, tired and cursing, a little later after a hard flog from London in a Toyota Land Cruiser that had been chosen in in an unfortunate moment as our back-up vehicle. Forty miles away the Countach waited in its garage. Everything was ready at last.

The Boxer and I had been together for almost a week. We had dribbled around town together and blasted down motorways at speeds approaching its maximum, and we were as close as I suspect it is possible to get to a beast with a heart as enormous and indomitable as this one.

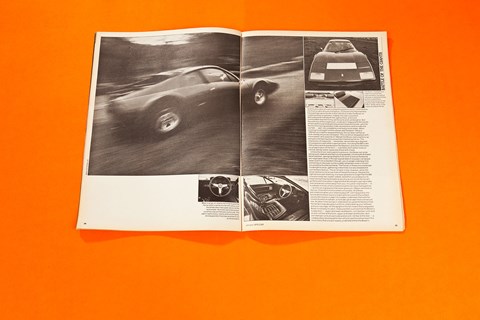

When the 4309cc flat-12 is very cold it grunts in response to the whining starter motor. You keep the key cranked over for a few seconds. Foot pumping, and certain that you’re going to drown it: two high capacity electric pumps and four triple choke Webers dump a lot of fuel into an engine. It seems to go on for minutes. And then there’s a grunt. You pump again. It dies. You try again. 10 or 15 times it will grunt back at you like this. But you’ve been told to be persistent; and then there is a bark. A fierce, stunning bark like that of a Formula One car except that the beat that follows is steady and free from the popping and spluttering of the race car engine before it warms. Nor is the noise quite so savagely loud. But, by God, it is an awesome wail, deep and unmistakably the end product of enormous strength. Interestingly enough, it isn’t that sharp or cutting as that of the smaller Lamborghini V12. It is basso supremo, and that is why you usually tend to sit and listen to it a moment before clipping the belt on and reaching out for the spindly steel lever in its six-slot gate.

There is nothing intimidating about stepping into the Boxer and driving off. It was designed to be one of the fastest – if not the fastest road car in the world. But it was also designed to be exceptionally easy to handle in cities, for a car so powerful. The engine fits naturally into such a role. Potent – the extent of 380 horsepower at 7500rpm and 302lb/ft of torque at 3900rpm – on the one hand but so polite and…um, docile on the other, the flat-12 is happy to glide up to 2000rpm and then slip into the next gear as the Boxer trickles along with the traffic. Although it has so very much more to give, it never insists on having its throttles opened further. Nor is there hunting or harshness from the transmission; not even at 500rpm in fifth, from whence you can accelerate more rapidly than most small cars can in first.

Complimenting such a powertrain is very light and smooth steering, and while the beefy action of the clutch and the solid clonking of the metal lever in its gate mean that a certain manliness is ever-present in the Boxer, the total feel is pleasing. And then you have a cabin of considerable civilisation.

Open and airy, it provides good all-round vision considering that the Boxer is such a big (it weighs 2722lb dry), mid-engined two seater. The driving position is fine, with simple minor controls.

So blending into the snarl of city traffic with the Boxer is a smooth and simple process, you work with relaxation and confidence, getting your pleasure from the intoxicating lustiness of the engine and the ca-clonk of the spindly fever (it’s a pleasingly efficient sound, that smack as the lever goes to neutral and then fully home). While the BB’s flexibility is exceptional – even by 12-cylinder standards – and the push is strong from 1000rpm, the engine does feel a shade flat until it nears 3000rpm. The effect isn’t exactly cammy but the push in the back becomes really solid. It just goes on getting stronger and stronger until you lift off – only because the tachometer says so – at 7750rpm. The acceleration is just one long, long superlative thrust forward, so outstandingly fast and yet so undramatic too for you have plenty of time to watch the orange tachometer needle sweeping around its bi g clear dial and prepare, as it strikes the warning sector at 7000rpm, to change up the instant it kisses the solid like at 7750rpm. The nose is lifting high with the fully-unleashed power then; the nose is a magnificent bellow. A dab of the clutch, a quick tiny movement of the forearm and the lever is forward, across and into second in a flash. The speed is precisely 60mph, the revs as second gear takes up are 5400rpm – solidly I the power band – and the matching of the ratios perfect for a change so smooth it does not interrupt the surge forward. It’s the same going into third at 80mph, and into fourth at 112 and then, if the road is there, into fifth at 148mph. Our BB took 5.3secs from 100 to 120mph in further, and 7.4 seconds in fifth, running on strongly to 170mph where its progress finally began to slow down a little. That’s the maximum we’ve seen so far in a BB, but there is more to come and a friend who owns one of the first Boxers to arrive in Britain has cruised down the German autobahns in excess of 180mph. Ferrari claims 188mph, and 0-60mph in 5.4secs.

And that figure is considerably quicker than the one in a set recently offered by Another Publication, a set of figures that must be rejected out of hand as unrepresentative of the BB. The first time we drove a Boxer in Italy we believed it to be superior in initial acceleration to its opponents. It is almost 100lb heavier than the Countach, and only has 5bhp more, but it is lower-geared in first and has a lot more torque, and at lower revs. It should be quicker to 60mph than the Lamborghini, if not right through the range. And indeed, when we took some readings on the BB that even Maranello Concessionaires had said was an extremely good example, we recorded a cool 5.3 seconds to 60mph and a staggering 11.3 to 100mph. The point is that all this is achieved with none of the wheelspin and drama that the others seem to imagine is necessary (you’ll only succeed in blowing the clutch on a car as heavy as the BB, and with such weight transference onto the rear wheels, if you try that trick). It needs a normal, everyday briskish take-off to get the car moving and then for the throttles to e flung wide open. Like this, the BB will record such awesome times all day, everyday; and soon you find yourself entranced by such mammoth but controllable acceleration and you tend to let the car have its head at every opportunity. Blasting full-bore out of motorway service areas is perhaps nicest of all, and since the fuel consumption when all this is taking place is just over 10mpg, that chance occurs fairly frequently.

But while one is full of nothing but respect for the creators of such a magnificent engine – we believe it is the finest on this earth – and the providers of such outstanding performance, controlled as it is from a cabin of such civilisation, it is hard to not to feel that they have perhaps gone too far in their efforts to make the Boxer so undemanding, so painless. Indeed, the ride is excellent, admirably pliant whatever the road surface, and more comfortable than the firmly-set Porsche and Lamborghini. But the softness of the suspension, no doubt in league with the results of having the engine weight placed well towards the rear, permits the front to rise a good deal under acceleration and to make the car feel…well, not unstable but not really stuck down. When cruising in a straight line this shows itself between 100 and 120mph as a slightly wayward feeling: the car does not feel as rock steady as you would expect. This condition disappears with more speed, and upwards of 140mph the Boxer really tightens up and gains the feeling of purpose that it lacked earlier on. The impression of insecurity – remember, we are talking in degrees of comparison with other supercars here, including the BB’s own little sisters and its predecessor the Daytona, and not in the more usual application of the term – manifests itself rather more on narrow, bendy roads,: especially those with crests.

Unless the driver really wants to press on, the Boxer will glide along such roads at very fast cruising speeds; it is smooth and well-balanced then, swinging steadily from lock to lock as the bends are negotiated. Even in the wet a great deal of the power can be put down (not from a standstill though; you must get underway first, and still be on the look-out for sudden wheelspin even in third if you prod the throttle too hard. ) The Ferrari in these circumstances is a delight to drive, gathering in the miles in a very relaxed and comfortable fashion. The air of calm is lost, however, when the driver wishes to use more of the performance. Despite the light and smooth steering, it is never possible to forget that the Boxer is a very meaty two-seater indeed, and when you endeavour to travel along these backroads as quickly as you think the car will go there are times when it appears that the weight is going to take over and wrest control away from you. It’s just an impression – in hundreds of miles of very hard driving the car never betrayed me – but it is an impression that never gives you 100 per cent faith in the car; it has the hint of a certain unruliness. And there are instances when your reserve pays off; coming quickly into bends where there is very slight vertical curve to the surface causes the nose to nudge into sudden understeer that calls for instant throttle shutdown, a more abrupt answer than one would like. At other times bumps in a bend will upset so upset the balance that the tail will snap abruptly out of line, really testing your reflexes and your courage, for the weight in the tail means that a wayward Boxer is not easy to catch. Does one then surmise that the Boxer’s suspension – upper and lower wishbones, coil/damper units and an anti-roll bar at the front; upper and lower wishbones and an anti-roll bar at the rear – is inadequately developed for the vehicle’s performance level? It is more likely that one will readily understand that the Boxer’s engineers have chosen to do it this way; to take the razor sharpness off it and compromise in favour of a superb ride. Thus, until you want to push it very hard the BB is extraordinarily mild-mannered considering its performance; it is undemonstratively but sensationally quick. But beyond that a driver who intends to use all the performance as often as possible might have preferred a different compromise.

So you learn to use the BB as a point-and-squirt machine, blasting along the straights – however brief – between the bends and then slowing (again, relatively speaking) to enter them. You then go around on the mild understeer side on neutral, gradually pressing the long-travel throttle open so that the car tightens its line and maintains a pleasing balance. As the exit comes clearly into view you can let it all go – and grin with delight as that masterpiece of 180degree engineering whoops out its power to lift the nose high and press you back into the seat. You storm ahead, keeping it flat through the range for as many gears as the road will permit, soaking it all up (for it is addictive to the extreme) and then peering carefully at the next bend to pick the smoothest surface for your entry as you brake hard and go chonk-choonk-choonk down through the gate and getting yet more pleasure from the feel and sound that comes when the changes are fast and perfectly timed. The Boxer, like this, is magnificent for it is conceivable to own it for the pleasure of that engine alone, and the big-hearted, relentless character it gives to the BB.

An annoying anomaly about the car is that although the cabin is so refined and reasonably roomy (there is a little space for coats and bags behind the seats and good oddments space in the door pockets) and vision that’s really quite good for city work, the luggage space in the nose is so small. Two modest overnight bags and a briefcase are just about all it will take, and should the space-saver spare need to be replaced with a punctured roadwheel you’ll have to shift the bags inside. And the penalty for using the car hard (you can come up with about 14mpg with quiet driving) is that even with 26,4 gallons in the twin tanks you’ll be stopping every 250 miles or so.

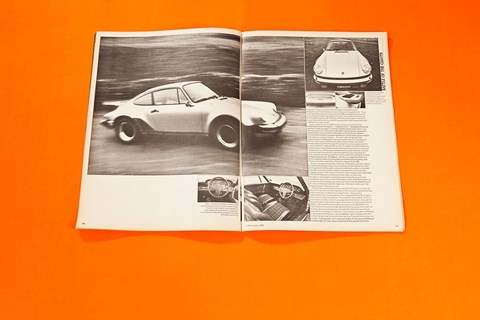

Performance with practicality is what the Porsche turbo is all about. Its dimensions are tight but it can carry four people across town if need be, and three on longer trips. It has quite a reasonable boot, and space for more luggage behind the seats if there are only two occupants. The visibility is excellent, and it is even easier to drive in built-up areas than the Ferrari. And yet it is almost as fast, despite having only half the cylinders and merely 2993cc. But from those six little cylinders come 86.6bhp/litre, fractionally more than the 86.4bhp the Ferrari gives from each of its litres (but a good deal less than the 93.7bhp that issue from each of the Countach’s 4.0litres) The maximum power is of 260bhp is developed at 5500rpm, about 2000rpm after the devilish little turbocharger than transforms the familiar Porsche flat six has cut in fully. Impressively, the Turbo has 253lb/ft of torque at 4000rpm and enough of it low-down to deal with the weight of 2515lb.

To get the Porsche underway you tug up a little lever on the transmission tunnel. It acts like a hand throttle so that when the engine catches a moment later it will idle steadily at about 2400rpm instead of stalling. Such a precaution, until it has travelled a couple of miles is all the care the Turbo asks for: it is as fuss-free as the Ferrari, and just as flexible. When the oil temperature gauge indicates that the flat six is war enough to work to the full, and after a quick check, at idle speed, to see that the dash-mounted oil level indicator is showing a satisfactory n reading, you can push the throttle right down, hold it there, and wait for the action. The pick-up is quick but nothing especially out of the ordinary to begin with, accompanied by a low rumbling that’s mildly reminiscent of certain V8s. But then the tachometer needles passes 3500rpm. A high-pitched whistling begins, and the Porsche leaps forward. It takes off like a jet, and just about as smoothly. You’re off! Your hand needs to be reaching for the gearlever as 4500rpm come, because by the time you’ve grasped it the needle will have reached its 6700rpm redline. The lever, somewhat rubbery when shifted about when the car’s stationary, belts through now with real efficiency, and lightly too, and you’re into second with full power on. And that is the time I like best in the Porsche: the potent, silken sweep forward from 55mph to 90. If you’re game, you can do it in any back-street: that’s what 0-60mph in 5.9 seconds means, with 100 arriving in 12.6.

But you’re in for more of a surprise with the Turbo if you start off slowly, without attempting to open it right up. Imagine you’re setting out on a frosty morning. The car’s cold, you trickle along gently while it warms up, on the lookout for slippery patches and tuning the radio with your left hand. He car flows along, the speed steadily picking up as it nears operating temperature. You squeeze the throttle harder coming out of a bend. You flow faster. A short straight. Still cautious out of respect for the frost, and still not quite warmed up yourself you press a little harder but not too much. Another bend, over another brow. Slacken the pace a shade, but not much. No trouble. Flow on again. Glance at the speedo – must be about 70mph. No – it’s a steady 110mph!

The Turbo is like that. Once past 3500rpm, with the turbocharger working, it just sort of glides ahead. You just stroke the throttle and it smoothly, very smoothly and without any apparent effort increases its speed. It’s a little uncanny really. On the same sort of road that will allow the Boxer to flex its muscles up to 160mph in very short order, the Porsche will sprint to 150 if it’s given full throttle. The thrust begins to fall off somewhat once past 130 but it winds on steadily to the ton-and-a-half mark, finally going on to register 158mph. A five-speed gearbox would help the car for fast cornering: some bends are two slow for second, and you come down out of the power unless you use first.

The Porsche feels rather more urgent at high speed than the Boxer. Beyond 130mph you start to know that you’re motoring – hardly surprising in a small car that has as part of its character that little squirming motion. In the Turbo it is minimal of course; little more than a faint jiggling of the wheel in your hands. Even this, however, can be unsettling until you’ve covered a great many miles in the turbo and learn to trust it. For at first it can, on rougher roads with plenty of bends and dips, feel a little insecure – or rather, too lively. It seems to dart about in little motions on uneven surfaces. Once you get past fighting it, and just let the car go its own way – this means that, as in the Ferrari, the Turbo doesn’t steer with absolutely clinical-feeling precision – you soon discover that those extraordinary Pirelli P7 racing-type tyres (on 7in rims at the front, 8in at the rear) give it roadholding the measure of which is made obvious in two ways: the manner in which the car will whip obediently around corners as you fling the wheel over quickly, and the G force that is generated as it does so. You can actually feel the grip of the tyres on the road just as assuredly as if you’ve planted your backside on the bitumen and are trying to move it sideways: the abrupt walls of the P7s transmit their message vividly.

With the Porsche’s degree of grip thus ascertained, and because it feels so small and tidy about you, there is the impression that you can fling it around bodily. Indeed so – if you are brave and skilled enough. I have seen Porscheophile Nick Faure do it. When you’re at that level a right foot planted firmly on the throttle is critical. Lift off and you’ll have an instant introduction to the shortcomings of the Porsche’s mechanical layout, even developed as brilliantly as it is. In more normal (but fast) motoring, if circumstances contrive to better the chassis the fact is gently announced by the advent of understeer. The nose just pushes out wide and the steering goes light. You will arrive at this condition as you try to accelerate hard out of the final curve of an uphill-ess bend. Indeed, the front pushes out far enough there to give you a significant scare. Thankfully the answer is simple and safe: back-off…quickly. The effect is noted in the wet too – especially into downhill bends. There is only one answer: brake very, very early and very gingerly.

It is in the initial stages of braking that the Porsche feels most uneasy, the wheel jiggly strongly in the hands, the nose attempting to weave and destroying your feeling of security. But when the big discs are hard on the squirming disappears and the car stops dead straight.

The brakes lock up all too easily though, and it is merciful that the Turbo continues to stay in a straight line. There is also the question of front end aquaplaning in the wet. The heavily grooved P7s help, but even small puddles at the edge of the road still drag heavily at the wheel, usually making you overreact and jerk the wheel sharply in the other direction. While this is annoying – the wet road cornering power is otherwise extremely high – it proves to be less serious than you think so long as speed and luck aren’t pushed too far

The basic Porsche 911 rides firmly; the Turbo rides hard. But the damping is well-considered and it is not uncomfortable. A driver who likes to feel his car under him, especially one so fast, will find it pleasing. At high speed the ride is fine, though not as soft as that of the Boxer nor as the Countach’s. The driving position is conventional in the Porsche, the wheel mounted very upright and pedals at a comfortable distance. The control/instrument layout is the epitome of efficiency except that the upper-right hand edge of the small, thick-rimmed steering wheel hides the steering wheel from 90mph to 130.

The big bucket seats grip you firmly and always comfortably, and there are details like furiously efficient windscreen wipers and washers, headlight washers, a rear window wiper, those rebounding crash bumpers, and the six-year anti-corrosion guarantee to make the Porsche a highly practical car for everyday use. One cannot help but admire its finish either: I believe it to be the finest in the world. So great a piece of precision construction is the car that the leather trim doesn’t really look like leather. The fit and cut is so exact that the hand-finished touch so pleasantly obvious in the Italian cars is missing completely. The Porsche’s cabin is for the perfectionist.

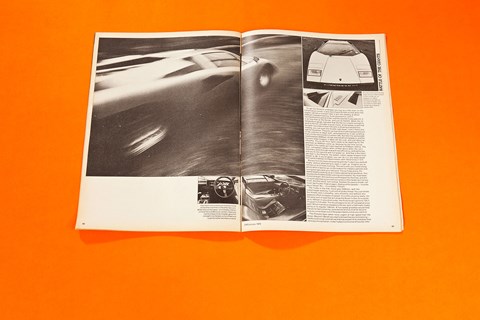

If the success of the car’s styling is measured by the attention it gets and the effect it has on people, then the Countach ranks supreme. It is an outlandish vehicle, almost unreal. Seeing it stark and alone high up on the Yorkshire moors made you feel as if you’d been transported to another time, and another planet. . While people admire the Ferrari for its flowing lines and its visual balance, and respect the chunky Porsche for the performance that its race-culture spoiler and fat arches so obviously spell out, they stand in awe of the Countach. We have seen already how the new Boxer, although designed to be so outstandingly fast, was built to a carefully-considered compromise to make it suitable for everyday usage. Lamborghini took a different tack: the Countach was intended to be an equally fast car but with as little compromise as was humanly possible. The shape suggests it: a look at the design and specification confirms it. The passengers sit well forward, the transmission is placed ahead of the engine so that it lays between the people and thus provides optimum weight distribution., even if it means taking the drive all the way back through the sump to the differential and using a great deal of magnesium for the castings to keep the weigh down. Maintaining such a minute frontal area meant locating the radiators behind the occupants’ heads, thus obliterating rear three-quarter fitting everything into such a tight and extraordinary shape meant very restricted cabin space. And yet despite these obvious limitations, and their effect on practicality, the design of the Countach’s body is impressive in other ways. There is room, for example, for a full-size spare wheel in the nose, along with the tool kit and items like the master cylinders and battery. And aft of the engine there is a roomy boot.

After you remember the doors on the Countach swing upwards, settling into the driving position is easy. The sills are wide (they house the twin 13.1gallon tanks) but it’s no trouble to swing the legs over them and drop into the one-piece seat. I’m 5ft 10in, and instantly at home behind the Countach’s wheel; but people over 6ft will find the headroom very restricted and will probably sit with their knees well up. The car really could do with more space inside. However, if you’re my height you’ll find that the reach to the (adjustable two ways) wheel is ideal when in the intermediate position and that while the clutch is slightly too far forward when fully depressed the brake and throttle are perfect. Vision to the front is magnificent: there’s nothing but that sheet of glass and the road. You might well be sitting facing a cinemascope screen with a road on it. But the vision to the rear three-quarters is disastrous should you need to reverse out of a garage; the door needs to be raised and the head poked out, and progress made only with great caution and constant checks.

The character of the Countach is entirely in keeping with the way it presents itself to you from the outside, and then presents you to the road as you sit in it: absolutely purposeful. It has a kind of direction to it even when standing still, like an arrow. Even after lying dormant for three weeks our Countach fired first twist of the key and then ran smoothly. And even after the magnificence of the Ferrari’s sound, the Countach sounded impressive. Savage and bitter and full of fight. It will, like the Ferrari and Porsche, lug down to very low revs in the high gears but it falls well out of its power band and there isn’t much push available. It soon becomes a pleasant matter of course not to let the 375bhp at 8000rpm/266lb/ft at 5500rpm V12 drop below 2000rpm, so you’re going up and down the box more than in the others when you’re in traffic. No chore. Countachs seem to be afflicted with a hefty flat spot from around 2400 to 2800rpm should the throttle suddenly be opened fairly widely. That hesitation, we found, is enough for the Boxer to surge away as its superior torque gets solidly on with the job. But once the Countach climbs up into its power band, effective from 4000rpm all the way to a gloriously viscous-sounding 8000 it clamps the bit between its teeth and hauls the Boxer in, tucking up nose-to-tail by the time they reach 110mph. We still do not know which of the two cars has the higher top speed. I have cruised at an effortless 175mph in the Countach and friend Bob Wallace found enough open road one day to get to 185mph and he said there was a little more to come. So who knows? Lamborghini claim 190mph, a calculation.

What mater s is that in a blindingly fast convoy along straight-ish roads there is very little difference between the three cars. Their individuals strengths overlap, and yet the Ferrari still manages to feel the most effortless.

However, there are considerable differences between the way the three cars behave when the drivers do attempt to use as much of what’s available as possible, especially when there are dips and crests mixed with the bends. It’s here that the Countach comes into its own, here that its lack of compromise pays off. Its suspension is set hard so that it rides very firmly around town. Yet, like the Porsche, it is not uncomfortable, merely reassuring. At speed in bends this stiffness means that the car stays extraordinarily flat, . It snaps around curves like an electric slot racer, answering the steering with lightning quick response and precision and displaying a honed sharpness that isn’t there in the other two. There is never any understeer, and only oversteer when you want it with power. It just goes around, and that absolute lack of body roll would make you suspect the speedo if it weren’t for the G force. The BB might have the most impressive engine; the Lamborghini the finest chassis.

It isn’t that the Countach has noticeably greater roadholding than the Turbo (than the Boxer, yes) but that it has such outstanding poise. Directional stability over the crests is magnificent; just as it is under brakes into descending curves. The car is as taut as a bow string, sharp as a sabre. And not just in the engine, suspension and steering either. It’s there is the way the gearshift, coming straight out of the box and working in metallic little movements, combines with the clutch and the throttle. Good as these functions were in the others, the Countach offers the driver new pleasures here. Again, it feels so purposeful ,making you drive with an easy precision and a clear, relaxed mind. It is this sensual pleasure, the driver’s sense of well-being that most of all is the difference between the cars, not their performance.

But lest one trusts too much in the Countach, lest one start to think it infallible because it is so very forgiving when the tail does go into oversteer, there is always something on a road like the one we had chosen to be reckoned with. And it happened not when the car was being driven to the full, but in a long, easy, constantly curving corner when the car was on the overrun as it slowed down. There was a sudden obstacle. I went to squeeze the brakes and steer round it. Smack, and the tail was close enough to 90degrees to the direction of travel and I was flat out keeping up. Neither Blain nor I have experienced such action under brakes before, especially brakes applied so lightly. It could perhaps have been a suspension setting problem peculiar to our car but were I to be a Countach owner I would be wary, just as the Porsche man must watch for puddles and tight downhill bends and the Ferrari owner for crests in curves and bumpy apexes. Setright was surprised at the noise in the Countach, and it is indeed loud. But I find – and it’s the same in the almost-as-vocal Boxer – that once the volume at quick road speed is noted it never worries me. Three hundred miles non-stop in the BB left me with no impression that it was annoyingly noisy, just interesting. But by the same token, the Porsche Turbo is extremely quiet. A Countach quirk is a loud zizz up the gearshift until the box is warm.

While the all-black interior of the Countach was very nicely detailed, it had paint problems. The metallic silver duco was bubbling in several areas, and it appeared as though the only cure might be a re-spray. The reason for such a serious fault probably stems from the fact that this Countach was built during a time of the factory’s greatest turmoil. Another disturbing factor was the way the headlight pods juddered. Like the Boxer, the Countach returns just 10mpg, most of the time.

But if the Countach is so impressive out on the road it is frustrating in the city despite the many sensitive areas of its design. The problem is the vision to any other direction than the immediate front and direct rear. Backing into parking spots is a nightmare, pulling out of oblique side streets is little better, and lane-changing must be executed with extreme caution. For these reasons, the car is best kept for use in the country, and preferably for long trips at that. It is here- the true domain of the supercar – that the Countach is superior. It corners faster and more easily, and gives the driver more pleasure as it does so. It has about it that outstanding air of purpose, an impression that makes you just want to keep on going and going and going in it, never to look back or turn around. It corners so flatly, and yet there is sufficient suspension control for it to ignore mid corner pumps and to prevent it bottoming in hollows even though it looks so low (the Ferrari will sometimes touch its tailpipes, sending a shower of sparks shooting out behind it). It is the unmistakeable lack of compromise about the thing, and the pervading sense of security that it presents for so much of the time. So given the task of driving long range as quickly as possible on a variety of roads, with maximum driver pleasure as an overriding factor, I would not hesitate to take the Lamborghini. It is the ultimate supercar. Both Leonard Setright and Doug Blain have reached the same conclusion. But to live with the Countach in town might be another matter. The undeniably attractive Boxer steps firmly forward here; that engine is an experience never to be forgotten, the feeling of relentlessness and civility ever-enticing. The Porsche doesn’t have quite the same sense of enormity about it as the Italians, but because of its rom, its robustness, its finish (and its 15-18mph!) it is not difficult to understand the strength of its own appeal even if its sometimes slightly frenetic character invokes the image of an overly brawny youth taking on the men.

The Porsche feels rather more urgent at high speed than the Boxer. Beyond 130mph you start to know that you’re motoring – hardly surprising in a small car that has as part of its character that little squirming motion. In the Turbo it is minimal of course; little more than a faint jiggling of the wheel in your hands. Even this, however, can be unsettling until you’ve covered a great many miles in the turbo and learn to trust it. For at first it can, on rougher roads with plenty of bends and dips, feel a little insecure – or rather, too lively. It seems to dart about in little motions on uneven surfaces. Once you get past fighting it, and just let the car go its own way – this means that, as in the Ferrari, the Turbo doesn’t steer with absolutely clinical-feeling precision – you soon discover that those extraordinary Pirelli P7 racing-type tyres (on 7in rims at the front, 8in at the rear) give it roadholding the measure of which is made obvious in two ways: the manner in which the car will whip obediently around corners as you fling the wheel over quickly, and the G force that is generated as it does so. You can actually feel the grip of the tyres on the road just as assuredly as if you’ve planted your backside on the bitumen and are trying to move it sideways: the abrupt walls of the P7s transmit their message vividly.

With the Porsche’s degree of grip thus ascertained, and because it feels so small and tidy about you, there is the impression that you can fling it around bodily. Indeed so – if you are brave and skilled enough. I have seen Porscheophile Nick Faure do it. When you’re at that level a right foot planted firmly on the throttle is critical. Lift off and you’ll have an instant introduction to the shortcomings of the Porsche’s mechanical layout, even developed as brilliantly as it is. In more normal (but fast) motoring, if circumstances contrive to better the chassis the fact is gently announced by the advent of understeer. The nose just pushes out wide and the steering goes light. You will arrive at this condition as you try to accelerate hard out of the final curve of an uphill-ess bend. Indeed, the front pushes out far enough there to give you a significant scare. Thankfully the answer is simple and safe: back-off…quickly. The effect is noted in the wet too – especially into downhill bends. There is only one answer: brake very, very early and very gingerly.

It is in the initial stages of braking that the Porsche feels most uneasy, the wheel jiggly strongly in the hands, the nose attempting to weave and destroying your feeling of security. But when the big discs are hard on the squirming disappears and the car stops dead straight.

The brakes lock up all too easily though, and it is merciful that the Turbo continues to stay in a straight line. There is also the question of front end aquaplaning in the wet. The heavily grooved P7s help, but even small puddles at the edge of the road still drag heavily at the wheel, usually making you overreact and jerk the wheel sharply in the other direction. While this is annoying – the wet road cornering power is otherwise extremely high – it proves to be less serious than you think so long as speed and luck aren’t pushed too far

The basic Porsche 911 rides firmly; the Turbo rides hard. But the damping is well-considered and it is not uncomfortable. A driver who likes to feel his car under him, especially one so fast, will find it pleasing. At high speed the ride is fine, though not as soft as that of the Boxer nor as the Countach’s. The driving position is conventional in the Porsche, the wheel mounted very upright and pedals at a comfortable distance. The control/instrument layout is the epitome of efficiency except that the upper-right hand edge of the small, thick-rimmed steering wheel hides the steering wheel from 90mph to 130.

The big bucket seats grip you firmly and always comfortably, and there are details like furiously efficient windscreen wipers and washers, headlight washers, a rear window wiper, those rebounding crash bumpers, and the six-year anti-corrosion guarantee to make the Porsche a highly practical car for everyday use. One cannot help but admire its finish either: I believe it to be the finest in the world. So great a piece of precision construction is the car that the leather trim doesn’t really look like leather. The fit and cut is so exact that the hand-finished touch so pleasantly obvious in the Italian cars is missing completely. The Porsche’s cabin is for the perfectionist.

If the success of the car’s styling is measured by the attention it gets and the effect it has on people, then the Countach ranks supreme. It is an outlandish vehicle, almost unreal. Seeing it stark and alone high up on the Yorkshire moors made you feel as if you’d been transported to another time, and another planet. . While people admire the Ferrari for its flowing lines and its visual balance, and respect the chunky Porsche for the performance that its race-culture spoiler and fat arches so obviously spell out, they stand in awe of the Countach. We have seen already how the new Boxer, although designed to be so outstandingly fast, was built to a carefully-considered compromise to make it suitable for everyday usage. Lamborghini took a different tack: the Countach was intended to be an equally fast car but with as little compromise as was humanly possible. The shape suggests it: a look at the design and specification confirms it. The passengers sit well forward, the transmission is placed ahead of the engine so that it lays between the people and thus provides optimum weight distribution., even if it means taking the drive all the way back through the sump to the differential and using a great deal of magnesium for the castings to keep the weigh down. Maintaining such a minute frontal area meant locating the radiators behind the occupants’ heads, thus obliterating rear three-quarter fitting everything into such a tight and extraordinary shape meant very restricted cabin space. And yet despite these obvious limitations, and their effect on practicality, the design of the Countach’s body is impressive in other ways. There is room, for example, for a full-size spare wheel in the nose, along with the tool kit and items like the master cylinders and battery. And aft of the engine there is a roomy boot.

After you remember the doors on the Countach swing upwards, settling into the driving position is easy. The sills are wide (they house the twin 13.1gallon tanks) but it’s no trouble to swing the legs over them and drop into the one-piece seat. I’m 5ft 10in, and instantly at home behind the Countach’s wheel; but people over 6ft will find the headroom very restricted and will probably sit with their knees well up. The car really could do with more space inside. However, if you’re my height you’ll find that the reach to the (adjustable two ways) wheel is ideal when in the intermediate position and that while the clutch is slightly too far forward when fully depressed the brake and throttle are perfect. Vision to the front is magnificent: there’s nothing but that sheet of glass and the road. You might well be sitting facing a cinemascope screen with a road on it. But the vision to the rear three-quarters is disastrous should you need to reverse out of a garage; the door needs to be raised and the head poked out, and progress made only with great caution and constant checks.

The character of the Countach is entirely in keeping with the way it presents itself to you from the outside, and then presents you to the road as you sit in it: absolutely purposeful. It has a kind of direction to it even when standing still, like an arrow. Even after lying dormant for three weeks our Countach fired first twist of the key and then ran smoothly. And even after the magnificence of the Ferrari’s sound, the Countach sounded impressive. Savage and bitter and full of fight. It will, like the Ferrari and Porsche, lug down to very low revs in the high gears but it falls well out of its power band and there isn’t much push available. It soon becomes a pleasant matter of course not to let the 375bhp at 8000rpm/266lb/ft at 5500rpm V12 drop below 2000rpm, so you’re going up and down the box more than in the others when you’re in traffic. No chore. Countachs seem to be afflicted with a hefty flat spot from around 2400 to 2800rpm should the throttle suddenly be opened fairly widely. That hesitation, we found, is enough for the Boxer to surge away as its superior torque gets solidly on with the job. But once the Countach climbs up into its power band, effective from 4000rpm all the way to a gloriously viscous-sounding 8000 it clamps the bit between its teeth and hauls the Boxer in, tucking up nose-to-tail by the time they reach 110mph. We still do not know which of the two cars has the higher top speed. I have cruised at an effortless 175mph in the Countach and friend Bob Wallace found enough open road one day to get to 185mph and he said there was a little more to come. So who knows? Lamborghini claim 190mph, a calculation.

What mater s is that in a blindingly fast convoy along straight-ish roads there is very little difference between the three cars. Their individuals strengths overlap, and yet the Ferrari still manages to feel the most effortless.

However, there are considerable differences between the way the three cars behave when the drivers do attempt to use as much of what’s available as possible, especially when there are dips and crests mixed with the bends. It’s here that the Countach comes into its own, here that its lack of compromise pays off. Its suspension is set hard so that it rides very firmly around town. Yet, like the Porsche, it is not uncomfortable, merely reassuring. At speed in bends this stiffness means that the car stays extraordinarily flat, . It snaps around curves like an electric slot racer, answering the steering with lightning quick response and precision and displaying a honed sharpness that isn’t there in the other two. There is never any understeer, and only oversteer when you want it with power. It just goes around, and that absolute lack of body roll would make you suspect the speedo if it weren’t for the G force. The BB might have the most impressive engine; the Lamborghini the finest chassis.

It isn’t that the Countach has noticeably greater roadholding than the Turbo (than the Boxer, yes) but that it has such outstanding poise. Directional stability over the crests is magnificent; just as it is under brakes into descending curves. The car is as taut as a bow string, sharp as a sabre. And not just in the engine, suspension and steering either. It’s there is the way the gearshift, coming straight out of the box and working in metallic little movements, combines with the clutch and the throttle. Good as these functions were in the others, the Countach offers the driver new pleasures here. Again, it feels so purposeful ,making you drive with an easy precision and a clear, relaxed mind. It is this sensual pleasure, the driver’s sense of well-being that most of all is the difference between the cars, not their performance.

But lest one trusts too much in the Countach, lest one start to think it infallible because it is so very forgiving when the tail does go into oversteer, there is always something on a road like the one we had chosen to be reckoned with. And it happened not when the car was being driven to the full, but in a long, easy, constantly curving corner when the car was on the overrun as it slowed down. There was a sudden obstacle. I went to squeeze the brakes and steer round it. Smack, and the tail was close enough to 90degrees to the direction of travel and I was flat out keeping up. Neither Blain nor I have experienced such action under brakes before, especially brakes applied so lightly. It could perhaps have been a suspension setting problem peculiar to our car but were I to be a Countach owner I would be wary, just as the Porsche man must watch for puddles and tight downhill bends and the Ferrari owner for crests in curves and bumpy apexes. Setright was surprised at the noise in the Countach, and it is indeed loud. But I find – and it’s the same in the almost-as-vocal Boxer – that once the volume at quick road speed is noted it never worries me. Three hundred miles non-stop in the BB left me with no impression that it was annoyingly noisy, just interesting. But by the same token, the Porsche Turbo is extremely quiet. A Countach quirk is a loud zizz up the gearshift until the box is warm.

While the all-black interior of the Countach was very nicely detailed, it had paint problems. The metallic silver duco was bubbling in several areas, and it appeared as though the only cure might be a re-spray. The reason for such a serious fault probably stems from the fact that this Countach was built during a time of the factory’s greatest turmoil. Another disturbing factor was the way the headlight pods juddered. Like the Boxer, the Countach returns just 10mpg, most of the time.

But if the Countach is so impressive out on the road it is frustrating in the city despite the many sensitive areas of its design. The problem is the vision to any other direction than the immediate front and direct rear. Backing into parking spots is a nightmare, pulling out of oblique side streets is little better, and lane-changing must be executed with extreme caution. For these reasons, the car is best kept for use in the country, and preferably for long trips at that. It is here- the true domain of the supercar – that the Countach is superior. It corners faster and more easily, and gives the driver more pleasure as it does so. It has about it that outstanding air of purpose, an impression that makes you just want to keep on going and going and going in it, never to look back or turn around. It corners so flatly, and yet there is sufficient suspension control for it to ignore mid corner pumps and to prevent it bottoming in hollows even though it looks so low (the Ferrari will sometimes touch its tailpipes, sending a shower of sparks shooting out behind it). It is the unmistakeable lack of compromise about the thing, and the pervading sense of security that it presents for so much of the time. So given the task of driving long range as quickly as possible on a variety of roads, with maximum driver pleasure as an overriding factor, I would not hesitate to take the Lamborghini. It is the ultimate supercar. Both Leonard Setright and Doug Blain have reached the same conclusion. But to live with the Countach in town might be another matter. The undeniably attractive Boxer steps firmly forward here; that engine is an experience never to be forgotten, the feeling of relentlessness and civility ever-enticing. The Porsche doesn’t have quite the same sense of enormity about it as the Italians, but because of its rom, its robustness, its finish (and its 15-18mph!) it is not difficult to understand the strength of its own appeal even if its sometimes slightly frenetic character invokes the image of an overly brawny youth taking on the men.