► CAR magazine’s iconic April 1984 cover story

► Boxer meets Countach, 911 Turbo and Aston Vantage

► This is Part One: click here to read Part Two

Road cars come no faster than these; together they amount to an astounding £185,000 and 1500bhp. For this test we took them to racing circuits and to Britain’s most challenging back-roads; we blasted them down motorways and hacked them in the city. And found, above all else, that unless you drive these cars together, you know very little about any of them

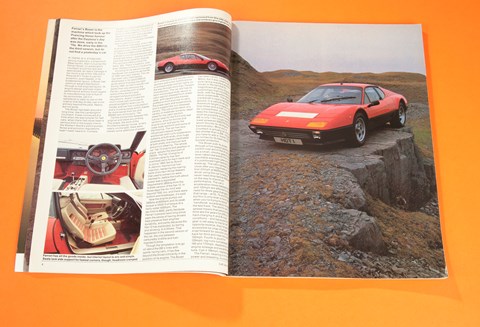

Ferrari’s Boxer is the machine which took up the Prancing Horse honour after the Daytona’s day was done, early in the ’70s. We drive the BB512i, the third version, but do not find a yesterday’s car

If there is a standard among supercars, a Greenwich Mean exotic, then it must be the Ferrari Boxer. A Lamborghini Countach is just too rare and specialised, an Aston Vantage is too much a car of the ’50s and a Porsche 911 Turbo is just too eccentric, even flawed, in its fundamental layout. A Boxer has optimum weight distribution through a mid-engined layout, its engine design and size chase performance without much regard to manufacturing cost or fuel or tax economies, yet it is satisfactorily easy to use on the road so that day-to-day use is not entirely beyond the pale. Nearly, but not quite.

The Boxer has been around a long time, like the Lamborghini Countach. It was conceived at a time when life was simpler for fast cars, when there had never been a serious kink in the supply-line to the Western World’s petrol pumps. Noise and pollution regulations hadn’t been heard of. It simply aimed to put the sophistication of a mid-engined layout, honed to a point of unbeatability in Ferrari’s sports/racing cars half a decade earlier, at the disposal of the enthusiast with a virtually limitless sum to spend on a car.

The Boxer manages, even now, to provide an intangible sense of occasion every time you step into it. There’s a relationship between a Boxer’s sounds and senses (and blood-red colour, usually) and the cars that have raced for Grands Prix and at Le Mans since the early ’50s. There’s tradition, and even 10years on there’s modernity.

Allowing for its advancing age, the Boxer can meet the demands of 1984 very well indeed. The car has been very intelligently developed in its latest BB512i guise which first saw the light during 1982, so that it resists rust better than any previous big Ferrari, complies with at least some of the world’s less-stringent exhaust pollution regulations, doesn’t make too much noise (yet continues to sound wonderful when you’re inside) and has fuel consumption and a cruising range which makes far more sense than the wild BB365 cars of the early ’70s.

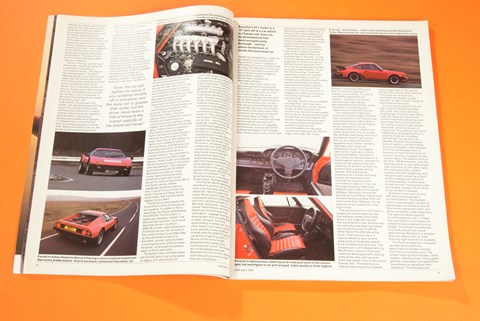

Yet the similarities between the original and latest are striking. The shape, the work of the Pininfarina design house, is very nearly unchanged; there were merely some additions of wheel arch extensions and aerodynamic spoilers and some modifications to exhaust pipes and tail lights on the way through more than 10years of production. The car still has its semi-monocoque body layout, a cabin section pressed from sheet steel, with square-tube frames grafted on front and rear to carry the power pack and suspensions, and to support the non-stressed panels. The old combination of a variety of materials remains: steel sheet for the cabin section, tubular steel for the front and rear sections, alloy for bonnet and engine cover and grip for the lower body sections and some of the flooring. The car has race-influenced unequal length wishbones-with-coils suspension systems at both ends, plus huge powered disc brakes (ventilated at both ends) and manual rack and pinion steering. The whole car, flat-12 engine and gearbox in place, weighs the best part of 35001b. The flat-12 engine of 5.01itres capacity has twin overhead cams for each bank and is (since 1982) fed by Bosch K-Jetronic mechanical fuel injection, replacing the roaring bank of six twin-throat Webers that used to extract (or were claimed to, before the truth about power was a legislated requirement) 380bhp from the 4.41itre version of the flat-12. In those days the rev limit was beyond 7500, too, and there were bottom-end breakages, it’s said.

Now the engine pumps out 340bhp at 6000rpm and its peak torque is 3331b ft of torque at a fairly sober 4200rpm. The rev limit is 6600, partly because Ferrari’s people have long since seen the sense of having drivers help preserve their engines’ durability, and partly because the flat-12 has expanded, by boring and stroking, to 5.01itres. That happened in the second version of the car, the one between carburettor 4.4litre and fuel-injected 5.0litre.

Though the temptation is to go on about the BB’s links with sports racing cars, it has few beyond the broad similarity in the position of its engine. The Boxer has been raced, notably at Le Mans, but it was never to be a pure racing machine and this shows in the fact that its magnificent all-alloy engine is surprisingly high-mounted in the body, with the gearbox and final drive underneath. The engine’s crankshaft is nearly two feet off the ground, in a vehicle whose maximum height is barely more than three-and-a-half. It is done for compactness, of course, to keep the mechanical bits bay as short as possible and it works (the BB is only 7.0in longer than the lower-powered 308GTB Ferrari which mounts its V8 engine transversely). Mind you, a Countach is actually an inch or two shorter than a 308 — though you have to add a ‘moral’ four to six inches for its total lack of bumper protection …

The Boxer puts its power through a five-speed gearbox, control over which the driver takes via a small, chrome gearchange lever raked rearwards from the inevitable exposed gate so that it’s positioned right beside his left kneecap. The ratio spread is fairly close after you negotiate a high first (53mph at 6600rpm) so that a driver using the car’s redline never need drop below 4500-4800 on the way to maximum performance. The car’s acceleration times between 60 and 100mph are affected by the need for three gearchanges in that range — at 53, 73 and 97mph, but this is only ever a handicap when you’re trying to record ‘handbook’ acceleration times on the test track. The terrific ratio spread means that second and third are the gears for difficult, hard-charging A and B-road conditions — and because first gear is set away to the far left, opposite reverse, they’re easily accessible for snap changes —snap forward for second, snap back for third and near enough to 100mph. Fourth is good for 129mph; top runs out between 160 and 170mph, depending on engine mileage and excellence of tune. Call it 168mph, realistically.

The Ferrari, bearing in mind its power and breeding, is a simply set out car inside, and it is quite easy to use. The engine starts instantly on the fuel injection these days and there’s none of the mildly temperamental woofling and snuffling that the carburettors used to pull near idle, especially when the car is cold. There is elastic power available literally from idle – near 1000rpm -to the redline (and beyond, for those who wear the blue-and-white apron). The car will pull fourth in town at 40mph, rather less than 2000rpm.

Sitting in the car, preparing to drive away, the Boxer lacks the Lamborghini Countach’s ‘intimidation factor’. The engine has started easily. The small steering wheel is set arm’s length away with the bottom part of its rim sloping more towards you than some, so that the heel of your palms rest comfortably on the rim as your fingers grip it at ten-to-two. The only modification we noticed for ’84 was a ‘flat’ on the side of the wheel facing the driver, better 😮 fit the thumbs. The instruments, the big pair that -natter, are straight ahead with the wheel rim cutting off their outer sections (the redline isn’t clearly visible unless the driver makes a special effort), there are oil pressure and water temp gauges in between them, and a further pair of ancillary gauges on either side. Most ventilation controls, the power window switches and fan controls are grouped on the low, thin console that houses the gearchange lever.

As you idle away from standstill, the Boxer steering seems dead and heavy. It kicks back a good deal over bumps. But as speeds rise the rim effort lessens and the sensitivity grows. The engine, fairly quiet to those outside, (especially compared with the Countach’s note), sounds terrific to those in the cabin. It’s the classic collection of buzzes, whines and barks that builds eventually into the most delightful shriek at full noise, reminiscent of the finest competition car sound ever concocted. At serious speeds the steering rim kicks and squirms in your hands as the surface changes – and there’s feedback over ruts – but the car can be guided accurately most of the time with movements of the wrists; the steering is quick enough for that. When you come to a hairpin and need to take a fresh handful of lock; it’s almost an annoyance, so satisfying is the business of guiding so much potential with little, timed movements of fingers and wrists.

The cornering characteristics of the Ferrari are classically mid-engined. The car is always immensely stable. The only serious risk on unfamiliar roads is that the car might arrive at a corner too quickly, perhaps under brakes, and understeer across the apex. There’s really no question of a Porsche-style oversteer twitch, at least not when the car’s riding on its ultra-forgiving TRX tyres. Sure, the car will tighten its radius if you suddenly throttle off in mid-bend, and the body roll is greater than some, but there’s never a threat to the Ferrari’s outright stability. You just need to reduce your lock a little to steer around. Under power out of bends, the car is as secure as it would be with rails beneath. That chassis and those tyres (240/55 VR415 Michelins mounted on those lovely Daytona five-star alloy wheels front and rear) could accept far more horses than 340 of the Italian variety, before breakaway became a serious risk. If you pick your corner and boot it, the car will hang its tail quite neatly. But it would never happen by accident.

The Boxer is undoubtedly the most refined of the mid-engined two-seaters. It’s better in many ways than its smaller stablemate, the 308GTB. The Countach, it beats very squarely indeed. The Mondial two-plus-two, built much later than Boxer, Countach, 308GTB or even Jalpa (bearing in mind that that car has its roots in the Lambo Urraco) is another step up the refinement scale. It’s smoother, quieter, almost silken in its progress over difficult roads. However, not enough Europeans seem to find it desirable…

The Boxer’s twin Achilles heels are its total lack of carrying space (a legacy of those old pre-oil crisis days when Ferrari thought they were making a statement, not a supercar) and its severe lack of cabin headroom. That second drawback it shares with the 380GTB. The properties combine to make the Boxer a poorer car for long distances than it might have been, though over bumps the driver soon learns to duck the head by instinct to avoid contact of cranium and headlining.

These problems have needed correction for many a year, and lacked it. Also, the seats have never been of the finest for such a car as this – minimal lumbar padding, insufficient bolstering to hold the body against the prodigious forces of cornering -but the car’s standard of craftsmanship is now absolutely excellent. The paint is deep and it gleams like the Aston’s and Porsche’s, the panel gaps seem to need to be only half those of normal cars, and Ferrari’s brochures now bristle with disproportionately long explanations about the tortuous anti-rust measures taken at the body-builders. There is now just no justification for even the person who pays £50,000 for the Ferrari to complain. The workmanship is in the Aston/ Roller class. Perhaps better.

The Ferrari Boxer remains the standard in exotics, for us. It may even stay that way when it is replaced, late this year, by a super-Boxer which uses a newly-developed version of the flat-12 with four valves/cylinder in a Mondial-look body. The car, to be called Testa Rossa, will have headroom and through-flow ventilation, luggage room and more power that is produced with a clean exhaust. It will be, quantifiably, a better car. On the other hand it will likely lose the pure, graceful lines the Boxer shares with the 308GTB (another car which is getting older) in favour of the extra length, possible extra weight and controversial looks. The new car will undoubtedly be more desirable for its function. However, it will be going some to match this car’s character …

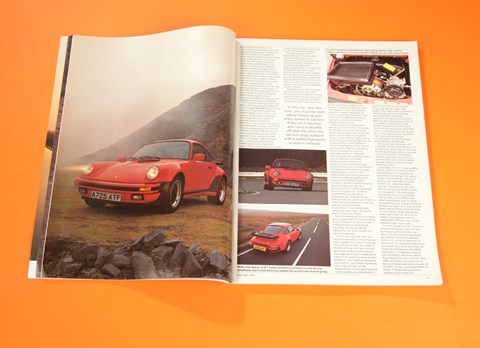

Porsche’s 911 Turbo is a ’77 spin-off of a car which is 2lyears old. Even so, its development has been exceptionally thorough — and for sheer excitement, it meets the best head-on

There is a powerful case to be made for not including the Porsche 911 Turbo in a group of ultimate exotic cars; it is too cheap by about £15,000 and it is the only one of the type which is spun-off from a lesser model instead of being hand-crafted in microscopic numbers by dedicated artisans.

On the other hand, there is a very strong case for putting the Porsche 911 Turbo right at the top of the list. It is the one car of the kind which began life as an out-and-out racing exercise (with all the dedication to performance which that implies) yet it is also the one car of the group that one could step into now, this minute, and drive to the other side of the Continent, knowing that it would not break down or deafen the occupants; that it would negotiate all ferry ramps and swallow a satisfactory amount of luggage. Furthermore, it would deliver 50 or 60percent better fuel mileage than certain Latin rivals which add only about 10mph to the Porsche’s 160mph top speed. Add to that, if the point still needs making, the fact that the Turbo has excellent parking protection, proven resale value and a standard of finish and quality control which helps preserve a buyer’s investment.

None of this is to say that the Porsche 911 Turbo is a model pillar of the establishment, or anything like it. Actually, it is an eccentric design indeed, with its engine as in all 911s, slung out behind the rear axle line. And from this layout springs the car’s most-discussed feature – its on-the-limit handling. Turbo tail-happiness, power off, is a well documented feature and it’s backed up by the fact that Porsche owners and sellers are more reluctant than most to commit their cars to the hands of the uninitiated. That’s how holes in hedges are made. But the car is not simply tail-happy, as will become clear.

Actually, the Porsche is a better package than other top-class exotic sports cars. For an overall length of 169in (around 5.0in shorter than the strictly two-seater Ferrari Boxer and more than a foot shorter than an Aston Martin V8, another marginal two-plus-two) the car provides a shallow but useable nose boot, fair accommodation for two plus occasional seating in the rear for eight-year-olds. The Turbo Porsche’s rather prosaic dash layout at least puts tacho in the correct spot, but switchgear is not well arrayed. Cabin quality is of the highest weighs a surprising 300lb more than the similar-looking 911 Carrera, but at 2870lb, it is still at least 500lb lighter than the Italians – and that’s using the optimistically light figures Modenese factories always quote. The Aston is something like 1200lb heavier than the Porsche.

This comparative lightness comes as an advantage of limited mass production; the Porsche has a monocoque body fabricated in sheet steel. It also has an engine which, because it’s slung outboard at the rear, needs to be lighter than most. It is, of course, the ultimate road-going version of the famous Porsche air-cooled flat-six, an engine which first appeared as a 2.0litre, normally aspirated, and has grown remarkably since. The engine came to the Turbo as a 3.01itre, producing 260bhp. That was in 1974, when the car was seen as a homologation special, dressed up inside on the orders of the then chairman, Dr Ernst Fuhrmann, to be more than a gutted racing special. With the engine’s expansion to 3.3litres and other engine developments that included an increase in the compression ratio of 7.0 to one, the output reached 300bhp at 5500rpm and 3131b ft of torque at 4000rpm. Running a maximum boost of around 0.8bar, intercooled and with boost available from not much more than 2500rpm, the car became a real rocketship in the right hands.

The emotive point of the Turbo’s shape has always been its rear; the fastback sweep of the body down to the huge tea-tray tail, the characteristic rear window and the radically extended rear wheel arches which cover its 225/50 VR16 Pirelli P7s (205/55s at the front). That massive stern’s natural tendency was once to swap ends at moderate speeds. It’s a lot better than that now. The suspension is all independent, by MacPherson struts in front and carefully-developed semi-trailing arms at the rear (springing for each rear wheel is by a transverse torsion bar). The steering is a manual rack and pinion system,

surprisingly light at low speeds but still fairly heavy when parking. The brakes are drilled and ventilated disc brakes, power assisted, on each wheel. Plenty of race development here.

As soon as you step into it, the age of the 911 design becomes very clear; this cabin was new 21years ago. The sills seem fairly high, the seats are low and the roofline seems to balloon up over your head (there’s almost room for a driver to wear a hat) and the slab dash, while functional, is clearly old. The switches are quite haphazardly arranged so that it’s only the driver who is totally familiar with the car who can operate it fluently (the powered sunroof switch is so well hidden that you must peer under the dash to find it) and the gearlever is mounted so that first and third (in the four speeds-only gearbox) are a reach away. The pedals pivot on the floor, VW Beetle-style, and the steering wheel is very vertical and high-mounted. On the other hand, the seats are terrific; leather buckets with firm bolstering, well designed with cornering support at their outsides and plenty of lumbar padding. And the dash, though prosaic, does position the tachometer straight in front of the driver where it’s needed.

But there’s one serious fault with the front passenger’s accommodation. The footwell room is unacceptably limited. All passengers are forced to sit with their knees awkwardly bent, and taller occupants suffer especially. The space evidently goes to accommodate the car’s 17.6gal fuel tank (which could hardly be smaller to give a decent touring range). The whole thing smacks of a more casual than usual approach by Porsche to a problem that only affects cars for their minority right-hand-drive markets. The Porsche engine’s character (as well as its particular specification) divides it totally from the run of exotic cars. The others have ignition buzzes, valve chatter, induction roar, timing gear whines, plus barks and wails from the exhaust to advertise their presence. The Porsche has practically none of this. The remoteness of the engine and the typically-turbo silencing effect of its KKK blower unit make it a quiet engine indeed. Engine noise only strays above a hum, even when it’s delivering maximum push at around 5000rpm. Only when ifs nearing the 6700rpm redline (and the actuation of its ignition cut-out) does the engine emit a delicious yowl even then the detail of the noise is lost in the body’s sound insulation. What results is a truly effortless power delivery, a giant push which throws car and self down the road and past 60mph in just 5.3sec. In fact, the car could get to 60 much, much faster if only its first gear stretched a shade further; changing at 6800rpm requires you to snap-select second at 58mph …

The engine’s strength from way below its torque peak of 4000rpm to its exaggerated 6800rpm redline (this one must be strong at the bottom-end) is why the car can support its prodigious gearing, and needs only four gearbox speeds. If you changed at 6800rpm on your way to the top of the performance curve, you’d find that second was good for just on 100mph, third for 146mph (you’d have swallowed up a standing quarter mile in something like 13.2 and 13.4sec, depending on your clutchwork and the grip coefficient of your road) and fourth, if the engine had the torque to pull maximum revs, would top out at a remarkable 199mph!

The gearchange itself is pleasantly light. There’s little sign of the fact that it must dispense 313Ib ft of torque in its silken movement. However, it isn’t the best-defined of gearchanges; there is quite a lot of distance across the gate and the lever feels, well, sloppy. But it is easy to use, every time, and the fact that there need only be four gears makes the car very fast in the sort of country where speeds vary constantly between 40 and 100mph.

The pedals and their location, like so much else about the Porsche, show evidence of being a poor system, honed over years to do a first-class job. But their movements aren’t as natural as those of pendant pedals, and there’s no getting away from that. The brakes, though immensely powerful, need understanding. They’re quite dead when you use them first but after they heat up, the bite is all you could wish. Of fade, there is none.

The engine’s style of power delivery is like no other. Whereas the Italians and the Aston have tremendous power from quite low down, which feels as if it grows more or less linearly, the Porsche is only fairly strong at 2000rpm, yet it takes off from about 2800rpm. There’s that feeling of the rate of acceleration itself accelerating, which is foreign to normally aspirated engines. That self-energising power, coupled with a lack of mechanical racket, allows great mouthfuls of distance to be swallowed with little effort from you or the Porsche. The fact that the steering is light, that there are only four very widely arranged ratios (second and third working together will cope with any British-roads situation) and thus gearchanging is minimised, only serve to enhance the car’s effortlessness at covering ground. You find yourself driving the car to maximise this; manoeuvring without flourish, picking cornering lines that use maximum road and require minimal wheel movement. It’s an immensely satisfying way to go — and quite distinct from the others.

But effortlessness should never encourage a lack of concentration in this Porsche. It has excellent roadholding and ultra-sharp handling, but its cornering behaviour can also contain the seeds of disaster.

In this car, near the limit, you must be right about choosing your entry speeds to corners. If you go into a bend too fast, and need to throttle off near the limit, the tail will snap outward with a speed that requires a racer’s reflexes to catch it. As one of our test drivers termed it, you need an opposite lock switch, not a steering wheel’. Of course, things can be stabilised by simply getting back on the power, provided there’s room. If not, the car will slide a long, long way at a very high speed. It’s under these conditions that the car’s short wheelbase (less than 90in) becomes apparent. Its reactions to throttle steering are instantaneous; there is a case for saying that in the hands of superior drivers this is the most manoeuvrable of all fast cars in on-the-limit cornering, but the Turbo needs a very, very firm hand and a driver whose concentration is fully focussed and reactions immediate.

We found that this power-off oversteer facility could be a joy on a racetrack, where the corners are known quantities and you can see around the bends. And where stabilising power could be fully applied. But road corners taken toe fast had the potential to be extremely dicey.

Strangely, the 911 Turbo suffers little in ride terms from its short wheelbase and comparatively long body overhangs. The ride is choppy below 40mph; the car is plainly over-damped for those conditions, understandably enough. But when driven over difficult crests with three figures on the speedo, the body stays beautifully flat and controlled. There’s less road rumble and steering kickback than in most comparable cars, though the front wheels do ‘walk’ a lot over bumps taken fast and the wheel twitches in your hands. Slow, wet bends need watching, too; 911s of all breeds have been known to understeer off them, having felt suddenly very nose-light.

In sum, though, the 911 Turbo is an electrifying car, a terrific fast touring proposition and a car which can be used as practically as a family hatchback without harm to it, or the investment, or the driver. It is several times more exhilarating to drive well than its Porsche co-flagship, the 92852, because it’s tougher to handle but ultimately, we think, faster. If we owned one we’d drive it very often, and take a private turn at the local racetrack every couple of months, to stay conversant with its limits. That would be using it properly and to the full.

Read Finding Out: Part Two here